By now I’ve made it abundantly clear in my previous reviews that I have a very high standard for storytelling in games. In fact the only game to have gotten a five out of five in the story category out of all my reviews is The World Ends With You (which might be mildly biased as it is my favorite game, but I promise to defend it later in the article). However, I think it is time to come clean and admit that most of my analysis of video game stories have been from more of a place of intuition than any particularly well thought-out set of criteria. Not that I think my previous review scores need reexamination, but a few months back I couldn’t give you a method by which I came to the conclusions. Having now graduated college and written a paper on beauty in narratives, however, I feel confident that I can articulate the reasons behind my strict scoring, and maybe help you judge the stories in the games you play yourself.

To begin, I had best summarize my previous research into beautiful narratives so that I don’t have to bore you with too much academic background and get into our favorite pastime faster. For this discussion, ‘beauty’ shall be defined as ‘the quality which impresses upon its witness a sense of its goodness and fosters disinterested interest’. ‘Disinterested interest’ is defined by Roger Scruton in Beauty: A Very Short Introduction as the interest people take in something for its own sake and not for any practical reason. The beauty of narratives specifically is broken up into two parts: the formal characteristics and the moral characteristic.

The formal characteristics come to us from St. Thomas Aquinas, which I read about in Umberto Eco’s The Aesthetics of Thomas Aquinas. These characteristics are three in number: proportion, integrity, and clarity. Proportion is the quality of a thing containing its elements in the correct proportion and relationship to one another, which in narrative manifests as being of the proper length relative to what the tale needs to accomplish, and as important scenes being longer and more fleshed out than less important scenes. Integrity refers fundamentally to something that is complete, though St. Thomas more precisely defines it as “…the complete realization of whatever… it is supposed to be.” (Eco 98-99) A story with integrity lacks none of its essential characteristics, including but not limited to a protagonist, a conflict, a beginning, middle, and end, ect. Clarity is a thing’s ability to communicate what it substantially is, and is seen in narrative as good style and language, as well as good symbolism.

The moral characteristic of a beautiful narrative is a little bit more controversial, but I will do my best to be brief. Firstly, it should be known that storytelling is fundamentally a power of exchanging ideas, like with conversation but containing more artistry and drama. There isn’t much in the way of theories about what makes communication beautiful, but I have reasoned that the goal of most forms of communication is to attain what is true. After all, the conversations that tend to really stick with us are the ones where people communicate their feelings honestly, or the ones where both parties arrive at some kind of profound truth. Thus the proclamation of truth is the most perfect and beautiful form of communication, and subsequently the most beautiful stories also contain the truth within their central themes and ideas. This isn’t to say that good stories are pure didacticism, far from it in fact. Tolkien in his essay On Fairy-Stories described fiction as a kind of “recovery” by which people are reminded of things they know to be true, but told from a perspective which liberates us from our burdened point of view and lets us see the world “…as we are (or were) meant to see them – as things apart from ourselves.” (Tolkien 57-58)

Lastly, a few words about why good narratives, or at least the best ones, promote that which is moral. It is self-evident that a great story with a bad moral is fundamentally worse than a great story with a good moral, for it is foolish to think that, given two maidens of equal physical beauty but opposite moral conduct, a sane man would willingly court a wicked lady over a righteous one. By contrast the idea of an amoral story, one which seeks something such as pure escapism or what have you, seems less necessarily worse from moral stories. Roger Scruton would in response label such a work as “Kitsch”, which basically means ‘voiceless art’, and assert that trying to divorce the subjects of art from their higher moral reality makes those subjects more banal to the viewer. Telling a story about a knight having a fierce duel without an underpinning meaning, such as a display of the virtues honor, duty, courage, or perhaps even selflessness, makes the struggle and violence of that fight into mere titillation, which may even cause a person to be numb to the virtues on display in similar stories. In short, amoral story telling makes itself and everything it concerns itself with less beautiful because of how pedestrian it ultimately makes its events.

With that you should now have a basic idea of what ‘narrative beauty’ means when I say it. But how can this understanding apply to video games specifically? Perhaps the broader question being asked is, how does the criterion of what constitutes a beautiful narrative change based on what medium it is being told through? The short academic response to give is that a story reaches maximum perfection related to its medium when it is told in a way that best takes advantage of that medium. This sounds like a bunch of jargon when read aloud, so let us give some examples to show what this means. The most basic form of telling a story that most of us can think of is simply telling it through oral narration, so let us use that as a base. Would it be possible to make any given narration into a beautiful book? The answer would be dependent upon whether the story would benefit from having more time to add details only comfortably achieved in prose, and especially if a story is long enough that the average orator would struggle to remember it all or possibly run out of breath.

What about taking a story and trying to make it a play for the theater? Well, the story would have to be of a nature that lends itself to the limitations of, and enhancement through, what can be accomplished with set creation and actors’ performances. If there isn’t anything in particular you can accomplish by making the story into a live performance, maybe present it in some other way. How about a film for the cinema? A story worthy of the screen has to take advantage of cinematography’s power to communicate ideas through perspective. If you want to shoot a film with static camera work, maybe just do a play. Keep in mind with all of these, this isn’t to say that stories which fail to leverage their medium’s advantages aren’t beautiful through some fundamental character if they have good narrative construction, but it is worth noting whenever you finish a movie and think “the book was better” or finish a game and think “those cutscenes were so numerous, why not just make a movie?” In short, a piece of art which is aware of its own medium and works with it to tell its story is going to be more beautiful than a work of similar quality that lacks any particular reason for its medium.

For games, this naturally means that the ones with the best integration of story and gameplay are going to be the height of their craft. Good writing and characters are found in all kinds of mediums, books especially, and stunning cutscenes are indeed impressive but nothing that couldn’t be done (and probably better) in a television series. It is ultimately in the interaction of the story being told and the actions of the player where stories in gaming really become worthy of highest honors. Most video games unfortunately come up a little bit short in this regard. To start with an example of where the average video game story is at, consider a game like Titanfall 2. The story is a pretty fun romp about overcoming a desperate situation and the bond that forms between Jack Cooper and BT-7274, and you as the player experience that journey for yourself as you struggle through the same battles as them. This is very much average in terms of enhancing the beauty of the narrative through gameplay, but this is as far as the integration goes. The game’s story doesn’t account for your performance in any way, so in some sense you’re more like an actor going through a script than a free agent making interactive decisions (to be fair this isn’t always a problem, but it is a missed opportunity that many games pass up). Titanfall 2 and many, many other games succeed in using the medium of video games to deepen the emotional connection between players and their characters to invest them in the story, and that is worth praising. But other non-video game stories can generate just as much connection without needing to vicariously walk in their protagonists’ shoes, so simple empathy is just easier in games, as opposed to being their uniquely beautiful strength.

The most egregious blight against narrative which occurs rather frequently in games is the good old ‘win in the gameplay, lose in the cutscene’ trope. A good example of this would be in Trails of Cold Steel II, because no matter how well optimized you loadouts are and regardless if you set up Laura to kill the boss in literally one strike, the cutscene that follows more often than not depicts our heroes panting with exhaustion as though a fierce fight raged while the boss simply goes “Hey not bad, time for me to actually start fighting like I mean it!” Granted, the I-was-holding-back clause is typically more justifiable then the always unsatisfying cutscenes that just show your character screwing up beyond your control, but it’s still not the most satisfying thing to endure as a player (and ridiculously overused in the Cold Steel games’ case). Sure such a complaint is regarded as a nitpick for most people, but the dissonance between the story of the gameplay and the story of the cutscenes does become noticeable when trying to evaluate games’ narratives as a whole, and not noticeable for the better.

Such is the complaint that juxtaposes best against the truly successful video games that use their interactivity to enhance their narratives, or even outright tell them. This is done in one of two main ways, either by dynamically reacting to the players’ actions, or by having gameplay which reinforces the narrative being told. I’ll begin with the former since they are the most obvious form of this to most people.

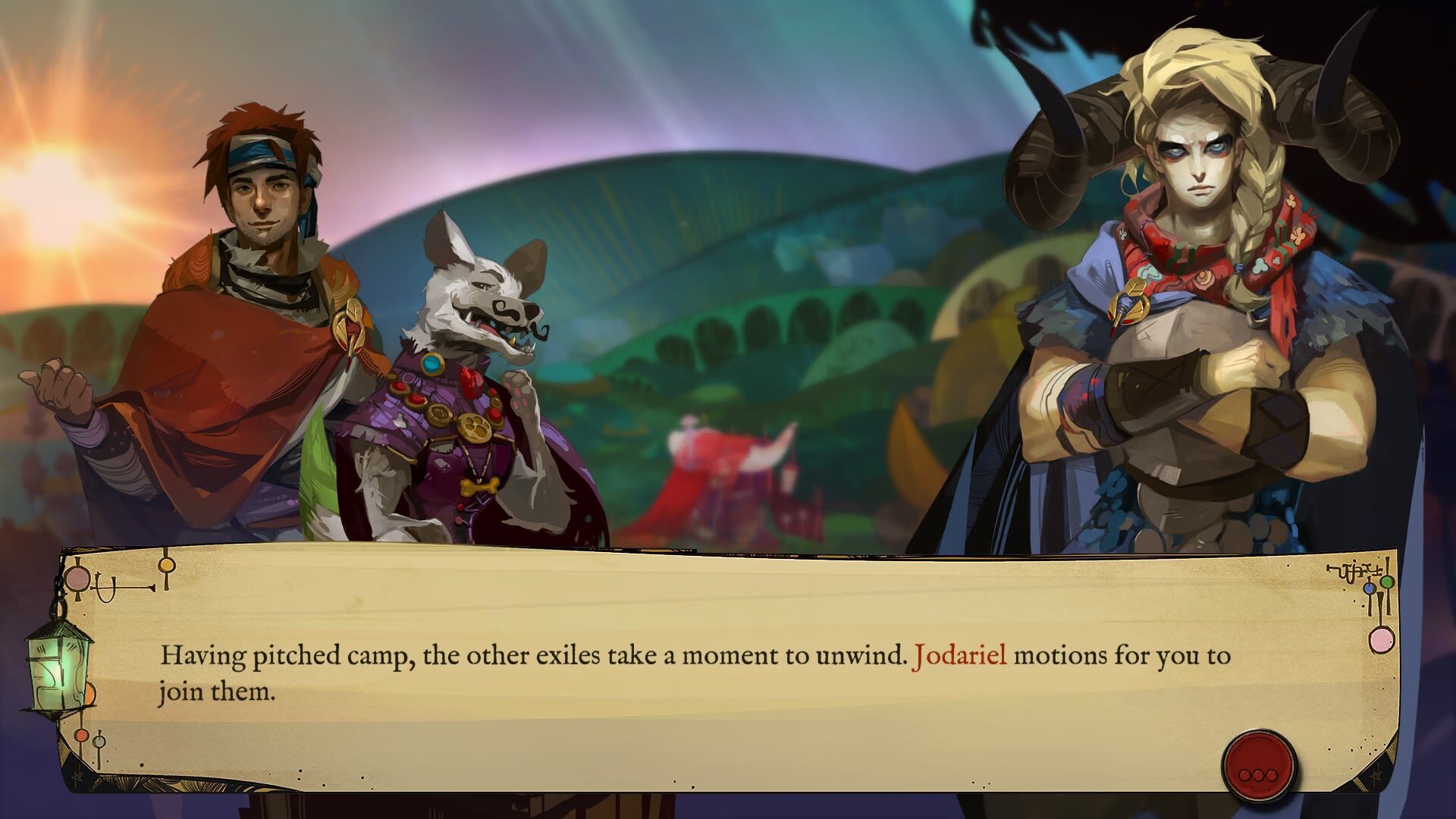

Narratives which branch out depending on the choices of the player are generally laudable efforts, insofar as that element of choice is deeply intertwined with the interactive choices gameplay per se presents to a player. I’d even go so far as to say that video games with multiple story routes are everything choose-your-own-adventure books want to be without the cumbersome user-experience of manually flipping through a physical object to continue the story. Branching narratives aren’t a ticket to beauty however, and in fact most players would agree that they more so have a tendency to make good stories better and bad stories worse. But given that the story being told is of the good variety, other kinds of gaming stories rarely captivate in quite the same way. For a practical example, Pyre by Supergiant Games has a story that winds up mostly the same on a macro level, but the micro is so rich in detail and affected by the player that the post-game epilogue has an absolutely silly amount of different possible things to say about each character. Who you spend time with, which Rites you prevail in, and which friends you liberate from the Downside can all have an effect on the characters’ lives, and it feels great to see it all come together by your hands. The prose of Pyre is already very respectful of the player’s ability to piece its fascinating world’s lore together, so the ability to enter into that tale yourself heightens its overall impact. Heck, there are elements which affect nothing of the the plot but still feel like major story beats on a personal level due to the game’s commitment to working with the player, such as recommending that Rukey shave his mustache and he actually does it, or getting to chose one of ten different names to call the Vagabond Girl. I better stop here in case I end up reviewing this one in the future, but in short Pyre is a great example of how to take a good story and make it more beautiful through empowering the player to have a meaningful role in the proceedings.

The other kind of interactivity which enhances video game narratives is gameplay reinforcement of the central ideas in the story. This is basically to say that there are games which generate understanding not so dissimilar from Titanfall 2 et al., but in such a way that the player does more than empathize on the surface level. This category encompasses many of the games that use the power of gameplay to communicate ideas which are difficult or impossible to convey otherwise. This is also where a branching narrative becomes more of an option than a requirement, as a linear game can communicate more specific ideas than the multi-route ones but only if the mechanical storytelling is good enough to justify it.

To demonstrate this, allow me to finally defend my high scoring of The World Ends With You. At base the combat gameplay loop also gives the player a sense of the physical trials Neku Sakuraba and company need to fight through to survive The Reaper’s Game, but the true genius of the gameplay-story integration comes from its complex two-character battle system. Neku at the beginning of the game is very much an anti-social jerk that very few people would empathize with, and in many ways the game’s narrative never does anything to justify his initial perspective. The player is nonetheless invited to experience his perspective, however, due to the way combat works. The first time any given player encounters the battle system they are almost assuredly off-put by how difficult it is to sync the attacks of both characters, and this is a vicarious experience of how Neku feels about working with his partner. As the game progresses, the player gets better at fighting as Neku learns to trust his partner, and a mirrored growth occurs between the two. Then when Neku is separated from his initial partner and forced to work with a totally different person, the player is presented with the challenge of taking the basics learned with the first partner and applying them to a totally different one who attacks enemies and generates Sync Stars in a vastly different manner, representing yet another burst of frustration Neku feels at opening up to yet another fellow teenager.

It’s the way The World Ends With You manages to make the player understand its protagonist’s internal struggle against his own nature without requiring prose-generated empathy that makes its narrative ‘felt’ in a uniquely impactful manner which makes it worthy of the title ‘beautiful’. Again, it is admittedly somewhat similar to the empathy building which most games are decent at, but the nuance of engaging the player directly in the story’s central theme of connection vs. isolation by making you feel Neku’s frustration through gameplay without ever explicitly asking for sympathy is delivered in such a way that no novelization or anime series could ever hope to replicate it, which is the mark of having used the medium well. This kind of storytelling isn’t particularly common, but it is almost always amazing when it does happen. (As a quick soliloquy, I’m sure there will be arguments made that the relationship between Cooper and BT create a similar bond through gameplay, but while it’s true there’s a minor learning curve to piloting BT it’s hardly anything on the level of The World Ends With You. Plus when you really break it down BT is more of a tool that strictly upgrades Cooper’s survivability rather than a person whose ability to increase Cooper’s survivability depends on the pilot’s response to them, because the two were always on mutually good terms and BT doesn’t exactly have personhood to begin with.)

And at the end of it all, this article isn’t to say that all games need to adopt one of these or any other techniques in order to become better games, because not all games aspire to tell great stories and that’s perfectly fine. I’m not asking Tetris for context as to why I’m putting blocks into lines, and the average sports game doesn’t really need context for why two teams of baseball players are having an afternoon together other than the self-evident context (although a sports game with a well-written story mode that explores the motivations and trials of its competitors as the season goes on would be TOTALLY legendary). I would even go so far as to say that there could in theory be a game with a 5 out of 5 story which does nothing particularly special with the medium, though it better be an absolute masterwork of literature, but if the average game bothers to include a story in its overall package then it isn’t above criticism. Being more capable of telling developers where their stories are good, bad, or underutilized, helps them in turn to make better narratives for their future projects.

So in summary, video game narratives are subject to the formal and moral criteria of beauty that all stories share, but also have obligations to incorporate their players’ participation into their narratives if they desire to reach the highest possible level of beauty they can achieve. I hope if nothing else this little exploration has given you a way to look at narratives and beauty in a way most people have seemingly all but abandoned, and in doing so has enriched your overall perspective. Just remember that beauty in the things we spend time on is important, for as the Church’s theologians have argued, the Beautiful is one with the True and the Good, and all of those are identical to our Heavenly Father. To seek beauty in human matters is to honor the Divine Beauty from which that beauty truly sprang forth, in some small way.

Did you enjoy this or any other Catholic Game Reviews article? Please consider becoming a donor on our Patreon, where loyal supporters can receive special benefits such as exclusive CGR stickers and the privilege of requesting games to have articles written about them. With your help, this site can keep going strong and searching for the most beautiful games to preserve the memory of, and a few games to use as examples of what not to do of course.