Josh Sawyer has been in the video game business for a while. Starting all the way back in 1999 on Icewind Dale II, he has quite the resume behind him. Nowadays he is the Design Director for Obsidian Studios and has helped design or write for games such as Fallout: New Vegas, Pillars of Eternity I & II, and Pentiment. He was narrative lead on New Vegas’ Honest Hearts DLC, which saw the player encounter two Mormons central to the story. Instead of being caricatures, however, their faith felt fully fleshed out. Many online found themselves drawn to these characters, having never seen people of faith portrayed accurately in a video game.

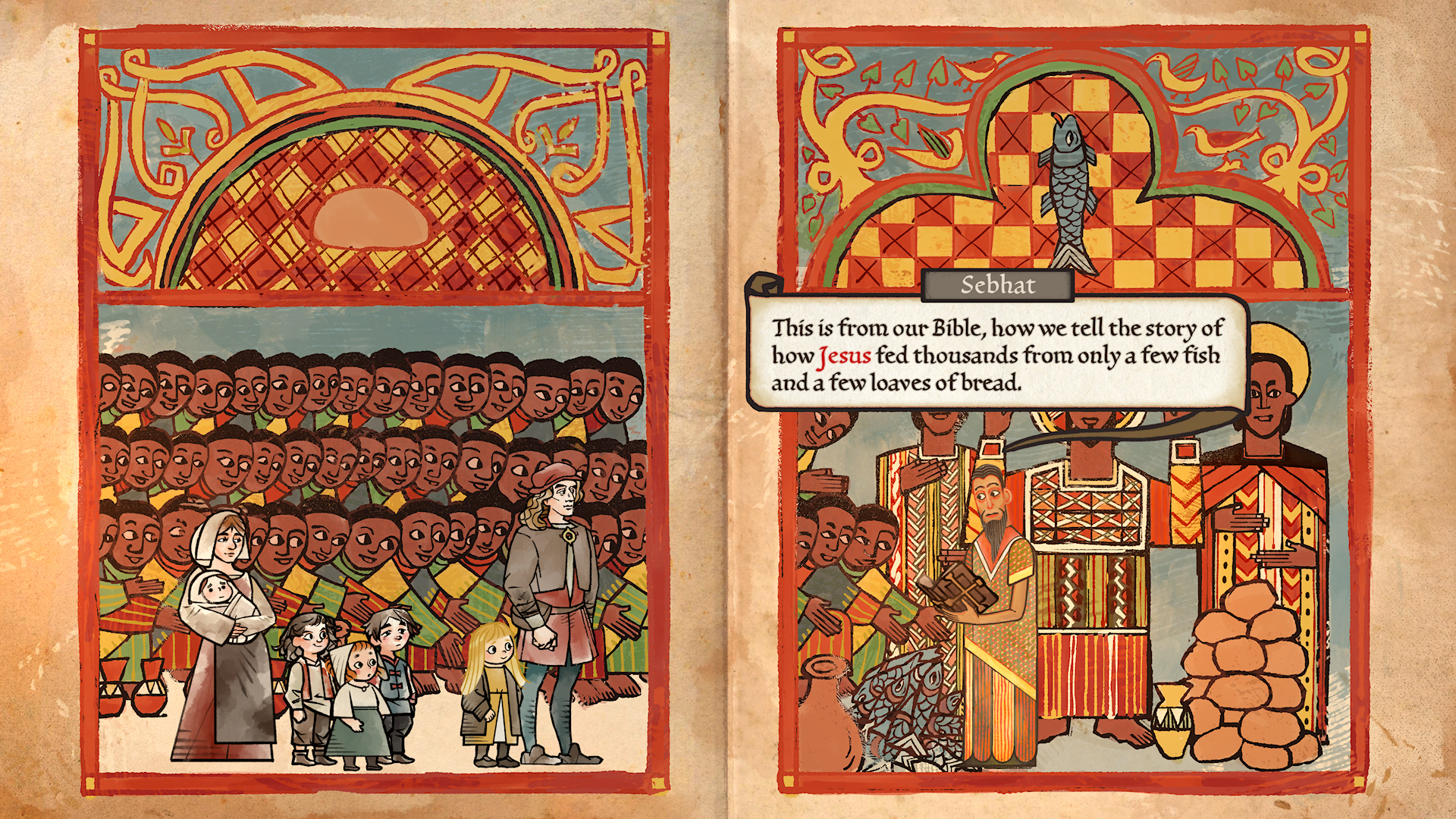

Curiously, these weren’t the last characters of faith Josh ended up writing. In 2022, Josh wrote a murder mystery set in a monastery called Pentiment. There are over 140 characters, and as it’s set concurrent to the Protestant Reformation, faith is an unavoidable topic for each of them. They run the gamut; in one conversation you’ll talk to a devout monk musing on the nature of truth in art, and 5 minutes later you’ll be discussing Perchta’s Wild Hunt with a pagan who still believes in Christ and his Saints.

Recently, CGR had the chance to interview Josh Sawyer. We’ve had this in the pipeline since our review of Pentiment, but they were (unbeknownst to us) preparing to port Pentiment to Nintendo Switch and Playstation 5. Now that that’s out of the bag, we found the time to sit down with him and discuss history and the nature of storytelling.

The transcript below has been edited for length & clarity.

Josh, we’re gonna be getting into some intense questions later on. But first things first: how do you like your eggs?

Hard. Over hard. I do not like runny yolks. I know that puts me kind of in a minority, but yeah, I have eggs fairly frequently and I always crack them and just get it out of the way. I’m like, let me mess up these yolks. Nice and hard. No surprises.

Pulp or no pulp?

As much pulp as possible, honestly.

You like to chew it a little bit?

Yeah. No, I really like high pulp. Some people get freaked out by it, but I like it a lot.

A few months ago, Xbox was running this snack food promotion where they had Starfield and Redfall branded Doritos. If you had to sell a Pentiment-branded snack food, what would it be?

Hmm, that’s a really difficult question to answer. I feel like it would have to be food that’s featured in the game. Maybe it could be an Emmental cheese, or Bergkäse, which is sort of the mountain cheese, the shepherds cheese. Could be Frumenty. What’s the truly emblematic food for Pentiment? I feel like it would be pulled from one of the meals.

If we were going with main brands, I could picture Wheat Thins or maybe Triscuits. But based on the game, I feel like a rye bread would make sense.

Actually, yeah. We could do a bread collaboration, that could be good.

While researching for the interview, I noticed you have some medieval styled iconography tattoos on your arms. What are those tattoos of, and what significance do they have for you?

Ohh, there’s a few. Probably the most relevant one is a tattoo of Joan of Arc I have on my right forearm. That was taken from an illustration by, I wanna say a late 19th century English historian. The tattoo on my other arm is just in a medieval style. It is by the late Pauline Baynes, who some people may know as the illustrator for C.S. Lewis, Chronicles of Narnia…later she was an illustrator for some of J.R.R. Tolkien’s works. The tattoo is actually of Smith of Wootton Major, who is a character from a lesser known J.R.R. Tolkien short story.

That’s one of the ones I have not yet read, which I’m kicking myself for. Cause I’ve been meaning to! I’ve read ah, well now I’m forgetting the name of it – Leaf by Niggle, that’s it. That one is a really good one. I would recommend that, and you can read it basically in an afternoon. It’s the most allegorical Tolkien gets.

The Smith of Wootton Major is also another one you can read in maybe an hour. It’s quite brisk.

You have a degree in history with a focus on the Holy Roman Empire. Why did you study that era of history in particular?

I’d always been interested in European history. Initially it was medieval or late medieval, and then in college I started getting interested more in early modern history. So the transition between the medieval period & the modern period (or what we understand as the modern period). Transitional periods in history in general are just interesting to me. There’s a lot of change going on, and with that there’s a lot of people fighting against the change. Initially I thought I might study Reconquista Spain. I don’t know really what changed, but my focus shifted north and went into Germany, the Holy Roman Empire, as we now know it.

I have some family connections to Germany and Austria, [as well as interest in] language & music. I initially went to school for music. So doing something in a German-speaking area seemed appropriate and I just had other pre-existing interests in that region. All those things kind of just came together. So I have a little bit of English history and a little bit of Reconquista era and a little bit of Renaissance Italy. But most of my studies were focused on the early modern Holy Roman Empire.

Back in 2012, you indicated you didn’t believe in any God. Is that still the case?

That is the case, yes.

What belief system were you raised in, and how would you describe your faith journey? I know you just said you don’t believe in any God, but based on things you’ve said before I believe you’d acknowledge there is a spiritual dimension to people.

I was raised in a household where both of my parents had been raised in different religious traditions. My father was raised Catholic and my mother was raised Wisconsin Evangelical Lutheran. (Actually, I might be wrong on that, but she was raised Lutheran.) Without revealing too much about my dad’s own personal life, he did not have a good experience with the Catholic Church. In fact, it was quite negative. And because of that, he really did not want to make me go to church. And so I was raised in a household that was not…well, my dad was kind of antagonistic towards religious organizations. But not hostile towards religion in general. Still, I didn’t go to church growing up. I grew up in rural Wisconsin and so I knew a lot of Protestants, but I also knew a fair number of Catholics. It wasn’t an extreme minority, so I knew many religious people around me. Mostly Lutheran or Catholic, very few non-Christian traditions overall.

I would say that I thought about it in the way that a kid might – it wasn’t like I had super advanced thoughts or anything. And then over time, I started reading more about Christianity and learning more about it in the context of history. And I remember thinking more about where I stood on agnosticism and atheism in college. I found that there were a lot of discussions that felt very fruitless because they became sort of arguments about definitions, which I don’t really find that useful. And so what I came away with was: I don’t believe that there are any identifiable higher powers.

And more importantly, I live my life as though there is no one sort of above, presciently seeing what I’m doing and judging me based on it. There’s a lot of ways you could put a label on that, but that’s pretty much what it comes down to. I don’t think it really changed much about how I live my life, although I do think that thinking through that changed how I interacted with people identifying by faith (or lack thereof). It just simplified and clarified where I stand on things. I do think that my viewpoint is as much of an act of faith as anybody else’s. Really, I don’t think like I have some special insight or anything. This is just the conclusion that I’ve come to in my life to this point.

That’s a totally respectable answer. And honestly, it was one that I was both expecting, but also one that I find fascinating because a lot of us find Pentiment to be so authentically Catholic. You know you did a great job with it – to the point where it’s like, “I know he said he believes this, but [seeing Pentiment], does he actually?”

Thank you. I will say, in studying religious history, at a certain point you have to wrestle with: Do you believe that the people that you’re reading about believe the things that they believed sincerely? One of the first major things that I studied was witch hunting & the history of witch hunting (which I should say is not a Catholic-only phenomenon. It was Catholic, yes. And then as soon as Protestantism came into existence, Protestants also engaged in witch hunting). When you read a lot of the accounts of these people who are accused of heresy or witchcraft, you do have to grapple with whether or not you believe that the people who are giving testimony were sincere about their beliefs. And if they were sincere about their beliefs, you have to examine the place from which that comes. The conclusion I came to is yes, they sincerely believed these things, and it was a core of their life, and to reduce it to something else is intellectually dishonest. And it makes it very hard to understand people and what they do.

The conclusion I came to is [faith] was a core of their life, and to reduce it to something else is intellectually dishonest.

And so the only way to portray religious people in a religious society is to try to really see things from their perspective, and to portray that as sincerely as you can. So I’m glad that it comes across that way because I do try to treat people with these beliefs with respect, even though they’re not my beliefs.

Why do you think faith-filled characters keep coming up for you? To name a few, there’s Joshua Graham, Daniel, and basically all of the characters in Pentiment. So many writers ignore or forget to write anything of a spiritual dimension to their character.

My background kind of required me to learn about [religion] in a historical context. But I’ve also noticed that religion either is not in games, or isn’t handled well, sometimes even with overt disrespect. I don’t think the gaming industry has a terrific track record with faith. It feels kind of disrespectful or inconsiderate. Not as well researched as one might want. In the Honest Hearts DLC, I made a number of mistakes there, especially when it comes to Native representation. I’ve already tried to say as much as I can [apologizing] for it, and I just have to try to be better in the future.

But with respect to how we portrayed a Mormon or a religious character at all, that had not really been a strong point, or even a point at all [in Fallout]. I wanted to try to do that. My goal with this was to try to show Christian faith in a post-apocalyptic environment. Mormonism is a very specific outlook on it, but I thought it would be interesting to see how that group would try to continue within a post-apocalyptic world.

With Pentiment it was more that I wanted to do something set in 16th century Europe, in The Holy Roman Empire. You can’t really do that unless the characters are in some ways grappling or not grappling [with faith]. They’re just religious, that’s the foundation of how they understood the world.

And you’re going to get a spectrum of that, and I hope I did portray a spectrum of it that seems plausible and believable. People grapple with their faith and live and change with their faith in different ways. So it was less about making a point and more about 16th-century Bavaria being very Catholic. And so the society and the character should reflect that as well as it can.

I know Joshua Graham wasn’t named after you, so just know that when I ask: how much of Sawyer is in Graham? Graham talks a lot about his doubts despite being a man of faith – Were you writing through some of your own doubts?

I don’t think I was working through my own doubts with Joshua Graham, but I was also recognizing that Joshua Graham was a character who had fallen (in multiple senses) and had come back into a life of faith that he was still struggling with. And even though he says at certain points ‘yes, I dealt with that in the past’, as you progress through Honest Hearts, it’s clear that he’s still struggling with certain aspects of his faith and how he views vengeance & violence. And so I wouldn’t say it was much about me. Joshua Graham was a person who had gone through a big arc, and in some ways was a prodigal son. But now [the prodigal son has] returned. Now that you’re actively engaging in the world, how do you continue? Part of the resolution of Honest Hearts is supposed to be you helping guide Joshua. That’s the perspective I came at it from.

If there is one thing that players have seen in a lot of video games, it’s a no-doubt zealot, right? I could archetype a character who is without doubt and extreme, with no subtlety and no nuance… I feel like if there are religious characters in games, often they are very over-the-top and extreme and have no nuance to them. And that was why it was important to have a very religious character who wasn’t like that. He’s very religious and he believes things very deeply, but he also has enough introspection to recognize the things that he’s done and also doubt the things that he’s even currently doing.

In regards to Pillars of Eternity: do you see fantasy settings as a space to explore moral ideas which might be more difficult to survey in reality? Or is it just “l wanna do a fantasy setting this time around.”

I think that there are different sorts of questions that come up and I wouldn’t say that we necessarily have explored those questions in the most ideal way. But there’s something interesting when you have a world where you have powers that are overtly manifesting right now. Not in the distant past, not referred to and passed down through traditions of faith. No, this dude did this, we saw it, a bunch of us saw it and we see evidence of it a lot. Deities even communicate directly with people!

One thing that I did intentionally is I noted that the sources of power for priests & paladins in the world is Faith and Zeal for priests & paladins, respectively. And it is actually personal, so you can be heretical, but intense, and you still [retain power]. It is based in faith, rooted in the deity, but it is actually a personal belief system that powers it, and what I like about that is that without direct confirmation from the deity, there’s going to be the potential for ambiguity and infighting and conflict. I think that’s an interesting aspect of doctrine and orthodoxy and the very human organizations that exist around faith.

We do try to explore some of that in another dimension though. The character Edèr is one of the more devout [characters]. He’s not a priest, he’s not a paladin, but he has a very deep faith rooted in Eothas, which in some ways could be viewed as the closest faith to Christianity. (I don’t think it’s that close, but like of all the faiths in Eora, Eothasians are probably the closest for a number of reasons.)

One of the things that Edèr struggles with (at least subtextually) is: you were brought up in a faith believing in these things as moral and ethical principles of life. The deity of that faith is gone. Does the moral and ethical imperative still exist without the deity telling you, without any sort of overt promise of reward or retribution for adhering or not adhering to that faith? If God isn’t there, are these [principles] still [true]? Is this how I should still live my life? Because I believe that they were given from God, but that they were also inherently true. In some ways it could be viewed as: if you are an atheist, can you live morally or ethically outside of religion? I would hope so. But a character in a fantasy world can also engage with that from a different perspective. Pretty much no one is saying that Eothas didn’t exist. But we’re saying that Eothas is gone. So what about the precepts of faith?

We’re going to get into a bunch of Pentiment questions now, but for those of you who want to go in knowing nothing: there aren’t story spoilers in the below questions. But we are going to be diving deep into the themes of the game. If you want to go in completely carte blanche, just return to this part later. [Editor’s Note: there are some minor spoilers related to side-characters. Matt lied.]

In a video you did on the remote development of Pentiment, you mentioned having weekly meetings where you’d watched reference movies. I was wondering if you specifically watched A Hidden Life. It was Terrence Malick’s latest film.

You know, we talked about it and I really [wanted to] but we couldn’t. We couldn’t find a place to stream it within the frame of when we were working on it. I really want to see it in life, because Terrence Malick is incredible. That story looks amazing. That actor, whose name I can’t remember, he’s in Inglorious Basterds and a number of other things, he’s just an amazing actor. [Editor’s Note: It’s August Diehl.] There is one scene that I’ve seen which is of the painter and the church, which is an incredible scene. I do really want to watch it. Unfortunately, we did not get a chance to watch it for Pentiment research.

It’s like you’re reading right from my questions, because I was just about to say: there’s that scene where he has a discussion with an artist where the artist says he paints their “comfortable Christ” instead of the true one that demands something of them. And that reminded me a lot of the struggle for truth that’s all throughout Pentiment. What were some key messages you were trying to impart through Pentiment, whether consciously or subconsciously?

Generally, they were about history and the fragility of history. Umberto Eco’s The Name of the Rose was a big inspiration for the game, but also books like Baudolino (also by Eco). Both of those stories really emphasize how tenuous our grasp on the past is. Whether it’s verbal or written down, it’s all passed along as a tradition. Whether willingly or not, we become guardians and transmitters of that for future generations. The late Hillary Mantle said something about history, which goes like ‘History is not what happened. History is what remains of what people wrote down about what happened, the way that they wanted to tell us.” When you really break that down, it’s so fragile and so fragmentary. We have very limited insight into things.

There are whole sections of time and places that we know nothing about: or we have one written record and no archaeological records. There’s a lot of faith involved in accepting that or doubting that. Look at the history of Kiersau and the Abbey, for example. Late in the game, you see an illustration of the founding of the Abbey. It doesn’t look like what the Abbey looks like now. Does that mean that the Abbey was laid out differently in the past? Does it mean that the artist took liberties with how they portrayed it? Who knows? You have no idea. [You might notice] the way that people will tell and retell stories and see how they differ. And they’re not necessarily trying to push some sort of falsehood. You see it especially in Act Two – if you talk to Nico about what happened in the first act, the way that he tells it is never the way that you saw it happen. You can call him out on it, but he’s not being malicious. It’s just someone told someone who told someone, who told him, and then he remembered it. Whether it’s oral or written, it’s a very fragile thing. And so we accept what we know about history on faith based on everyone who came before us.

In the video you did on remote development, you talked about maintaining the esprit du corps of the team once COVID hit. As the director, how did you handle that switch emotionally and logistically? Was there any spiritual difficulty that came about while working on this game?

I think that the spiritual or emotional crisis was the one that everyone was dealing with, right? We were very isolated. I’m very used to going to work every day. Even now, even though we can work remotely, I still like going into the office. I just like not being in my house all the time. And so not really being able to go very many places, not being able to meet with people face to face… I am quite accustomed to informal conversations with people, and that becomes harder when you need to actually initiate a call. So I’m very grateful that the team size was very small because we all knew each other pretty well and I could talk to people pretty regularly and frequently. That made it a lot easier. We did have a few events that allowed us to actually meet up physically a couple times, which made a huge difference. I don’t think we ever reached any true crisis points. We all considered ourselves lucky that we had jobs, that we could do remotely, that we had a small team, that we had a really good trajectory leading into production… many, many teams around the world were incredibly disrupted by COVID. And I’m just so grateful that we were on a good course and it was minimally disruptive. In some ways, in the long term it was helpful because we had the infrastructure to bring on people from Europe that were really critical to helping us get the game done. So I think we fared a lot better than a lot of teams and I think it’s because we went into it better than a lot of teams did.

What made you want to tell Pentiment’s story in particular?

I always loved the setup of The Name of the Rose: a murder in an Abbey featuring lots of monks. But I wanted to set it later, and so when you get later into the early modern period, monasteries are not doing well. The history of monastic orders [is turbulent]: starting with Benedict of Nursia and the Benedictines, there’s this constant desire to found new orders and reformation movements [keep occurring].

So I liked seeing an Abbey that was, in some ways, quite old fashioned (relative to other monastic orders that might be more recent) and also more old-fashioned in the sense of being a double monastery. At this point in time they existed, but they were quite rare because the Pope had made it clear to not do this anymore. And I love the idea of places in transition. So I had a number of things that were in flux: I wanted to tell stories that were quite medieval about groups and organizations that felt truly medieval in their character, but also I wanted to talk about the emergence of the early modern world.

I also didn’t want to just have monks. I wanted to also show how the women [and sisters] lived and how it was similar in many ways, but not exactly. And I wanted to show peasant life and emerging middle-class life and how those in some ways were similar, in some ways were different. I wanted a really wide spectrum of society, with lots of different characters.

And so by having Andreas as an artist who moves between both worlds, like he lives in the town among the peasantry, but he works in this Abbey and the Abbey is through Father Gernot… clearly Andreas has a lot of sympathies and friendships within the Abbey, even if he’s kind of set up to be in conflict with the Abbott in a number of cases, and he has a lot of friendships within the town, even though there are clearly some really awful people at work in the town as well. It was an interesting way to bridge those worlds and show how there is conflict not only between them, but also between the old way of doing things and the emerging world.

Pentiment has much to say about pursuing your vocation and occasionally struggling with what you once felt called to do. I’m thinking in particular of – I’m gonna forget the names because I played it in November and there’s a lot of characters.

There’s a lot of characters.

I’m already bad with real people’s names, you know, but the sister and monk, who, spoilers for people, leave at the end of Act II.

Matilde and Wacslav.

They talk at one point and essentially say ‘Never let anyone convince you that you have to stick to your vocation if that means remaining in sin.”. What advice do you have for those struggling with their vocation? And what place did that character come from? I know you weren’t the only narrative designer for Pentiment, but in case you were.

I did most of the religious characters that really talk a lot about their faith, so I did write Matilde for the most part. It came from wanting to show again the spectrum of devotion, and the struggling with adaptation [ to religious life]. People change over time, and their relationship to the world around them and their inner world changes as well. They’re going to reconcile it in one way – some are going to reconcile it toward the cloistered life, toward their vocation, and other people aren’t. And there are people that leave, whether it’s for more or less dramatic reasons than Matilde. Not everyone who takes vows stays in that vocation for their entire life.

Many don’t.

Sometimes it changes. There’s so much to know about that life, even within a single order, that I can’t possibly know. I mean, there are people like Matilde, who Matilde is not irreverent. She’s not like Zdena. Zdena is a character that I think many could view as being spoiled, and a little more capricious. She’s mad to be there. She’s upset that she is a nun, and she’s very rebellious about it and kind of has a devil-may-care attitude. Matilde is not like that. It’s not that Matilde dislikes being a nun, but she struggles with it because of the vow of chastity specifically. It takes her a long time to determine that she can’t remain there because she can’t reconcile those things. So she returns to a secular life.

And so [Matilde] was really there to portray the nuance of that, in contrast with other characters who either have different struggles or don’t struggle. Like Zdena, she’s just kind of mad. And it’s not like she’s upset because she can’t observe her vows. She’s kind of mad that she had to take vows. She didn’t want this life. And then you have someone like Illuminata who is kind of aggravated about being forced into that life just because she feels like she didn’t have much of a choice, but is still quite religious so she takes her vows very seriously. So I think it’s just to show one of the many different ways that characters live life under the vows that they’ve taken.

I wanted to take a moment to praise the game for its theological and philosophical accuracy. Did you have any theological consultants when it came to that area of the game?

So I didn’t have theological consultants as such. I did have my advisor from college, Edmund Kern. A side effect of studying witch hunting is that you need to be fairly familiar with canon law. Because even though in the end, people who were found guilty of things like witchcraft were tried in secular courts and sentenced by secular authorities, there was huge overlap between ecclesiastical authorities and secular authorities, and much of the basis of it is in canon law. There is a lot of talking about what laws applied & didn’t apply. I did study the New Testament academically in college. And so I would return to that on occasion, but we did not have, as it were, a theological consultant. There was no one from the Catholic Church that we consulted about matters of theology, in part because most of what we understand we needed to understand through a historical lens.

For example, a point that does come up had to do with the Seal of Confession. And canon law on the seal of Confession now is really clear. It’s much more clearly defined, specifically like “do not do this -even if you’re not a priest, do not do this. That was not the case then. And so we had to take the sources not from the perspective of a Catholic now, but from Catholics then and what they wrote about. So we would look at [sources like] Tentler, who wrote a book on what confession was like around the time of the Reformation (Sin and Confession on the Eve of the Reformation). So we didn’t consult with modern Catholics because it would be from their perspective – we had to go to the historical sources and try to understand it through their perspective.

At the end of Act I, there’s an execution, and it’s particularly brutal if you choose to watch it. What do you find the artistic merit is to showing off mature content?

[For that example in particular], there’s a a story element, which is: “Hey man, you’re gonna be present for the fruits of your labor. You were involved whether you want to accept it or not. You were involved in this person’s condemnation to death.” And I think that there’s a lot of portrayals in historical or fantasy settings about what execution was like, and you know, they’re kind of hand-wavey about what the process is. And in the case of Pentiment, I wanted to [be accurate]. I read a fantastic book by Joel F. Harrington called The Faithful Executioner, and it is about a 16th-century Bavarian executioner and what his life was like. He kept uniquely remarkable records of his life and the executions that he performed. Understanding how the executioner as an instrument of justice in this world operated is what was really fascinating for me to read about. And I wanted to portray it not for the sake of shock, but for the sake of helping people understand: this is what happened. People would be required to come see this, because this is a performance of justice that the community has to come see. In many cases, you were obligated to come see it.

In a lot of cases, people were portrayed as happy and cheering. Obviously we don’t know what happened at every execution, but in a lot of cases they would be really upset to see a member of their community being killed. A lot of people thought it was unfair. Depending on who gets killed at the end of Act I, you see people you know saying that. There did need to be guards present because sometimes people, if there weren’t guards, would try to prevent it. Or they would attack the condemned themselves if they thought that the execution was going to be too swift. And there were differences in how the executions were performed – with a sword, with a cord…it varied again based on gender, age, relative social rank. If a priest were condemned, they would be defrocked.

But also there was a religious authority present there, because you have to say last rites – you have to potentially recant for what you’ve done before dying. That whole conversation at the end between the secular authority and the executioner was a way of safeguarding the executioner, where the authority says “this person is acting on our behalf, and I’m telling them to do it.” It says in a formal way, “Hey everybody, I know emotions are high here, but this is the execution of justice by someone appointed by us. And I’m telling him it’s OK to do it. So leave him alone”. Because in a lot of cases they would not.

And if an executioner botched, which did happen, (you can see it happen in one of the executions [in game]), sometimes the crowd would attack the executioner because they found it unacceptable. It was a wild and crazy thing, and it’s not shown in great detail. Since we have a lot of detail on it, I thought it would be illustrative to actually portray it, whether or not you actually watch the event.

So the maker of Andrei Rublev, Andrei Tarkovsky, he describes the artistic process as follows (from his book Sculpting in Time):

“It is a mistake to talk about the artist ‘looking for’ his subject. In fact the subject grows within him like a fruit, and begins to demand expression. It is like childbirth . . . The poet has nothing to be proud of: he is not master of the situation, but a servant… For him to be aware that a sequence of such deeds is due and right, that it lies in the very nature of things, he has to have faith in the idea, for only faith interlocks the system of images,”. He insists faith is necessary for art to come forth from an artist. What are your thoughts on that?

Overall he’s right. I’ve talked a lot about the process of making Pentiment, so I won’t go into it in great detail. But the basic idea of making a historical game came in like 1999 or 2000, right when I got in the industry. But that specific form just spun around over many, many years where I had no opportunities. I had a vision, but that vision changed – it was a specific confluence of opportunities and inspirations that really resulted in being able to make Pentiment. And it’s a confluence of so many influences in my life. Specific pieces of media, specific historical events, Andrei Rublev itself! I mean the structure of the story is taken from Andrei Rublev. So I fully believe in that. I do think it depends on how you define faith. There is a certain level of ego and arrogance in saying, “I can make this. I have a picture of a thing in my mind that I believe I can make and I can share it with other people.” If you don’t believe that there’s something in you that you can bring out, not by yourself, but with other people, then you’re just never gonna do it. So yes, I think that from my perspective it was about seeing these images of this thing. I’m a very visual person. In a lot of cases there are specific images of events. I don’t wanna spoil anything, but you know there were very specific things that were anchor points where I would say “I know this is going to happen here. I don’t know how we get here, but I see this and I feel like this feels true to where we’re going.”

I will say, very early in my career when I was kind of ad hoc put in charge of finishing up a project, I overheard another designer saying “Josh doesn’t know where he’s going.” And I said, “Hold up. I know exactly where I’m going. I just don’t know how to get there.” And that is very often the case. I have images and I have pictures and I have experiences – I know that we can make this feeling. I know that we can convey this thing. I have an idea how to do it. I don’t know how to do it, but I know we can get there. I remember before Pentiment was even a thing. I had an idea of a historical game where everything was handwritten out one stroke at a time, and I remember I told my girlfriend at the time about it. And she said that sounds awful. She said ‘waiting for everything to write out, stroke by stroke sounds absolutely miserable and not fun.’

And I said, I understand what you’re saying, but I think that there’s probably a way that we can do it that would feel like it captures the physicality of writing without it being annoying. And I hope we found it.

(The answer is 20% of the way through the first character, the next character starts, so you will have like four or five characters in progress at any given point in time. When we first started it, it was unbearably slow. And I was like, OK, it is slow, but how can we keep this physicality but make it not annoying? If you speed it up too much, you lose the individual strokes. So we can’t do that. So I kept going back to this: here’s what I’m trying to capture. Here’s what I’m trying to do, and you know, we just work together and we found it. So yes, there is a certain amount of faith that we can get to the image, get to the experience even if you don’t know how to get there.

Absolutely. Tolkien has this great lecture called On Fairy Stories. It’s where he coins the term eucatastrophe, as well as the idea of sub-creation, which is the idea of like: we’re made in the image of our maker. So what does that mean? What’s the image of our maker? Well, he makes things. So that means we also want to make things. So when we’re sub-creating, it’s that idea of: we have these images in our head, how do we put them on paper, how do we put them in a game?

It’s interesting you should say that because Smith of Wootton Major which, as you know, obviously I loved it enough to get it tattooed on my arm. But Smith, the title character, receives a star from Faery on his forehead. And he keeps it and carries it with him as a gift. While he has it, everything he makes as a blacksmith is imbued with this kind of fairy beauty, and he sings while he works. And people gather around to listen to him sing. (I also sing while I work.) But it felt very much like this idea. At the end of the story, he passes it on to another generation. He wants to keep it, but the fairy tells him ‘It’s not for you forever. You have to pass it on to someone else.’ And the reason why it resonated so much with me is – I want to create things and I want to pass on these things in my head. But also I want that to inspire other people. I feel a great deal of that.

And with that, we’re at time. Pentiment is out now for Nintendo Switch and PlayStation 5. Obviously, it continues to be on Xbox Game Pass. I reviewed it back in November and to keep it short, I’d heavily recommend it.

Josh, thank you again for your time and for your openness. It was a real pleasure speaking with you, and I’m looking forward to future projects like Avowed and whatever else Obsidian’s got cooking.

Thank you very much.

One response to “Interview with Josh Sawyer”

Fantastic intervew