While it lacks the global recognition of later titles in the series, Final Fantasy IV still has the honor of having received numerous ports, re-releases, sequel episodes, ports of said sequel episodes, and even a visual re-imagining on the Nintendo DS. Clearly, this game, originally released for the Super Famicom in 1991 in Japan (and as Final Fantasy II on the SNES in the west), has some staying power. Most recently, it was re-released as part of the Final Fantasy Pixel Remaster series, which aimed to bring its 16-bit era visuals onto modern systems. That’s the version replayed for this review, however most of the discussion would apply to any iteration.

In transitioning to a new console generation, Final Fantasy IV combined the best elements of its predecessors into a new tale. The job mechanics introduced in I and developed further in III return, but this time are intimately linked to the protagonists in a more character-driven story like II. It’s a story that, despite its age and a bit of regrettable dualism, has laudable themes deserving of CGR attention. (We clearly don’t have enough JRPG content anyway.)

Final Fantasy IV begins in the skies over the Blue Planet, with the kingdom of Baron’s airship fleet en route to Mysidia to seize their crystal. The fleet, called the Red Wings, and their captain Cecil have been given orders to take the crystal by any means necessary, though they’re not privy to any reasons for their mission other than to secure Baron’s prosperity. The Mysidians resist, but the Red Wings easily overtake them, and we immediately see Cecil’s growing apprehension. He does his duty, but is sickened by what he had to do to achieve it. He questions the king, who sends him on a new, seemingly simpler mission, but it goes tragically wrong and sets Cecil on a new path that forms the heroic tale we then follow.

That tale is briskly and impeccably paced. (Until the end, perhaps, so I guess it’s a little peccable). Along the way, we meet a memorable cast of heroes and villains. There’s the brooding dragoon Kain, thoughtful and courageous white mage Rosa, and the stubborn but good-natured engineer Cid, and quite a few more all arrayed against the forces of evil. Final Fantasy IV also goes places in a way the series hadn’t quite achieved yet. There’s been a blending of high-technology and high-fantasy in FF since the beginning, but I think it’s fair to say IV took advantage of the new hardware to realize that blending in a new and exciting way for the series.

For a modern player, though, the environmental art isn’t going to be revolutionary – it’s pixel art emulating the SNES experience, but it still all looks very polished. Character sprites in combat are colorful and unique, but in keeping with the original they’ve still got a small scale out of combat. In recognition of this, Final Fantasy IV often uses the combat screen to play out scripted encounters to better render characters’ emotions and reactions. In terms of music, I can do little but heap praise on Uematsu’s work. While I tend to enjoy other entries’ soundtracks more, IV has plenty of memorable pieces, such as its overworld theme, the Battle with the Four Fiends, and the Theme of Love. As with all of the Pixel Remasters, these tracks have been arranged anew, and generally I’d say they’re very faithful improvements.

Mechanically speaking, Final Fantasy IV is minimally complex, standard JRPG fare. Combat is turn-based, though this title introduced the Active Time Battle (ATB) system to the series. Rather than entering your party’s commands all at once and letting combat play out as dictated by speed statistics, battles take place in “real time”, with time gauges for each character informing you when you each can act. Actions in combat are what you’d expect – basic attacks, magic spells, items, and unique abilities based on a character’s class.

Overall, it’s hard not to feel like IV is a bit of a step back mechanically, as character customization is essentially nonexistent. There are occasionally impactful equipment decisions to make, but that’s about it. There might be a time when you’ll keep a particular weapon because you prefer its alternate attack when used as an item, or maybe you’ll equip something that’s got a particular elemental property. Generally, though, the bigger number is better, and little more thought is required. Fortunately, the script, pacing, and scenario design really save the day. Until late-game grinding, the story moves characters in and out of your party, forcing you to adjust your strategies, and propelling you along the narrative to see what happens next. Final Fantasy IV gets you invested in the characters quickly and keeps you moving fast enough to stave off ennui (at least until the final dungeon, which can be a bit of a slog compared to the rest of the game).

In terms of quality-of-life updates, the Pixel Remaster offers a few, chief among which (at least in my estimation) is the lifting of inventory restrictions. No longer need you store your loot in the capacious gullet of the Fat Chocobo. Additionally, there’s a bestiary, art gallery, and jukebox mode. There’s some graphical flourishes here and there as well, but in general changes made as part of the Pixel Remaster are non-invasive and do not depart from what you’d remember if you’ve played an earlier iteration.

While later entries of the series offer more in the way of character customization and mechanical depth, there’s much in Final Fantasy IV that still shines more than 20 years after its original release. Players revisiting the series know what they’re getting into, but this could also be a good entry point for new players interested in a taste of what Final Fantasy has to offer. Whether you’re a series veteran returning to the Blue Planet, or a first time player, you’ll be treated to a straightforward and timeless tale of heroism with themes of self-sacrifice and in particular for Cecil, an uplifting arc of repentance. (Spoilers ahead for a decades-old game.)

Cecil’s journey certainly doesn’t start off on a pleasant note – if one were to take FFIV’s references to The Inferno a step further, one could even say he’s “midway on his life’s journey”. Cecil is introduced to us as an honorable Dark Knight, one of Baron’s most elite warriors. Dark Knights master powerful but self-destructive arts in service of the king, and while Cecil is clearly a capable soldier we can see that he’s troubled by the tension between his duty and what he knows to be right. He’s guilt-ridden over memories of the violence against Mysidia, shares his concerns in private moments with Rosa, and even confronts his king. In response, the king sends him on a mission with a horrific agenda hidden from Cecil until it’s too late. Cecil resolves then and there to oppose his king and do what he can to bring an end to Baron’s violent hegemonic designs.

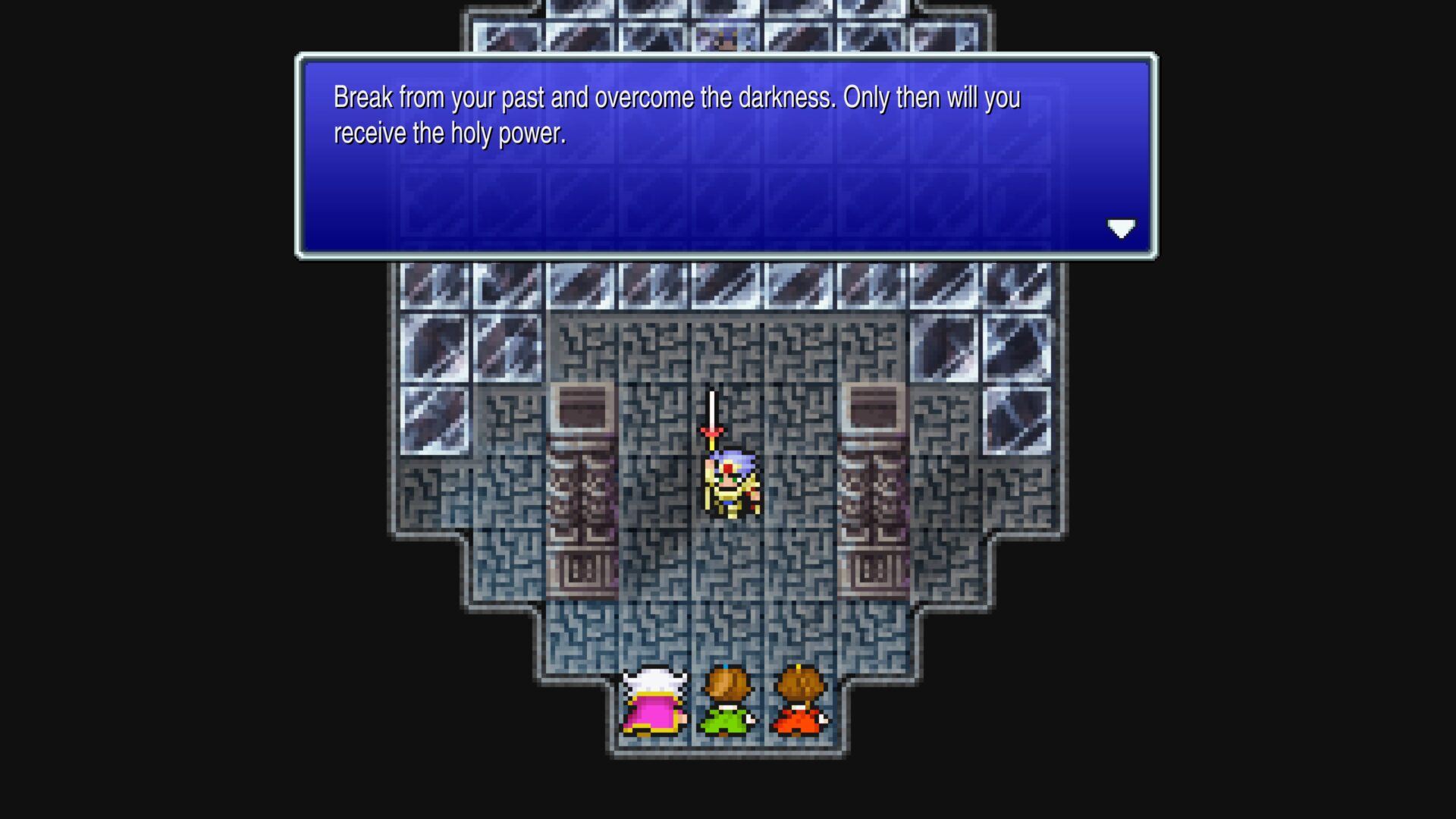

The imagery surrounding the initiation of Cecil’s redemption couldn’t be more fitting. The noble knight learns of a power he can obtain that will aid him against Baron, but must first wander a desert before he can face the challenge necessary to earn it. After gathering allies and helping a friend convalesce, he’s ready to climb the Mount Ordeals, the summit of which is home to Cecil’s pivotal trial. On Mt. Ordeals’s peak, Cecil enters a chamber lined with mirrors and must literally face himself in order to leave behind his Dark Knighthood and adopt the holy mantle of a Paladin.

Cecil, now in gleaming armor and holding aloft an ancient holy sword, is an image that is stirring on its own, but watching that transformation beginning in the desert and ending on the mountaintop is all the more poignant when viewed with eyes of faith. For one, it’s an echo of Jesus’s ministry: He begins in the desert, and His sacrificial mission culminates on Mt. Calvary. Since we are called to imitate Christ, and are fulfilled to the extent we do so, we can look at Cecil’s journey as a fantastical imagining of our spiritual journey.

Through fasting and prayer, we can imitate Christ’s entry into the desert wilderness, and more clearly recognize our dependence on God. With that relationship rightly understood, we can examine ourselves, and as Catholics approach the superabundant mercy of God through the sacrament of Reconciliation. Then, renewed by God’s grace, as St. Paul writes in his letter to the Ephesians “put on the whole armor of God.” (Eph 6:10-18)

If you’ll indulge me in a little amateur linguistic sidebar, there’s even a bit of accidental meaning hidden in the name of Cecil’s desert home base, Kaipo. If you squint just right, it looks like the biblical Greek word for an appointed or fitting time, καιρος. Jesus’s first words in the gospel of Mark are, “The time is fulfilled, and the kingdom of God is at hand; repent, and believe in the gospel.” His word for “time” is “καιρος”. (It happens to be in the passage from Ephesians above as well.) Then, you could say Cecil was εν καιρῳ…or in Kaipo…when he repented. I know, I know, the original’s katakana doesn’t support it, “ρ” sounds like “r” and not “p”, etc.. I like the connection too much not to mention it, and now you can’t unsee it.

Cecil’s mission doesn’t end there, and the remainder of the game contrasts his path of Light with the darkness of Final Fantasy IV’s principal villain, Golbez. On the one hand, this leads to some frustrating dualism, because it’s a JRPG and we apparently can’t just have nice things. Two characters do make the claim that good requires evil to exist, and one of those sours the conclusion a bit. However, I’d argue that Final Fantasy IV’s treatment of the ways of Light and Dark is more consonant with the Didache‘s ways of Life and Death than any dualistic system. Darkness in this game is clearly evil, and any dialogue to the contrary is the exception rather than the rule. Let’s just assume Mysidian philosophers can set those two straight after Cecil and crew save the day, as Final Fantasy IV is a journey worth seeing through.

Scoring:

Overall: 80%

Gameplay: 3.5/5

Visuals: 4/5

Sound: 4/5

Story: 4.5/5

Parental Warnings

Final Fantasy IV has a few suggestively designed enemies, a little bit of language from one attitudinal character in particular, and very mild fantasy violence. There is a scene involving the villain’s severed hand, but there’s no blood and it’s hard to call anything in FFIV‘s pixel art intense.