Long ago before the advent of modern gaming technologies, role-playing games lacked the means to weave the kind of narratives we often expect of them today. This led to a greater emphasis on mechanical emulation of its tabletop counterparts, where the appeal was playing custom heroes and challenging devious dungeons. Such was the legacy that influenced the design of turn-based RPGs for most of the genre’s life, but the genre was also content to shift focus from gameplay innovation to storytelling innovation as the decades progressed. And yet it was that very legacy which Atlus drew upon when creating the title which would go on to be one of handheld gaming’s most beloved cult classic series, and this year we have been given the chance to revisit that title all over again. But was this game worth treasuring enough to return to (digital) store shelves once more, or was it a dud to be left in the labyrinthian depths of gaming history? The adventure begins now!

Developed and published by Atlus and released in 2007, Etrian Odyssey is a cartographic dungeon delving RPG originally for the Nintendo DS, and earlier this year for Nintendo Switch and PC via Steam. Its premise involves a group of adventurers descending into a forested chasm to solve the secrets of its vast maze, probably for fame and fortune or something. Players interact with the game mostly through turn-based combat and first person dungeon surveyance, with menu management and light dialogue reading to spice things up. Bear in mind that I played the PC release for this review, although I did play the original DS version all the way back in high school so I can give some small comparative analysis on that front. Also just putting this out there, some people have the idea that the HD releases are “remakes” but they are actually just remasters with some overhauls to the dungeon mechanics to better fit single screen gameplay.

They came from a land afar, five brave adventurers who graced the town of Etria. Their leader was a benevolent healer who guided his companions with great care, though his true motivations and even background was difficult to parse. At his side was his brother, a holy knight of a crusading order whose stoic composure grounded the whole fellowship. Traveling with them was an adventurous girl from a small village, whose bright enthusiasm and thirst for glory belied her natural talent for swordplay. Next was a prodigious transmuter from the royal academy, a quieter man than most but no less determined to uncover the labyrinth’s hidden knowledge. Finally there was the traveling slayer from a land even further away, whose quest to seek out and defeat every monster in the world led him naturally towards Etria. Upon the parchment in the explorers’ guild did these five etch a simple name that would echo across generations: Lys. This is their story…

… Not! Ahahahaha!

The true story of Etrian Odyssey is actually quite simple: a fearsome labyrinth near the town of Etria known as the Yggdrasil Labyrinth is a forest over a giant chasm leading deep into the earth. Recently after a long ban on exploration, adventurers from all over were invited and commissioned by the town’s governors to uncover the mysteries of the maze, but so far the maze’s sheer danger has killed many glory seekers and consequently slowed exploration to a halt. The game begins with you arriving in Etria as yet another unassuming guild off to challenge Yggdrasil, except yours may just be the one to go the distance… if you dare. As I alluded to earlier, the story of this game is comparatively sparse to most JRPGs and sometimes you can go an entire play session without reading a single story-driven event. Your ability to stay invested in this story comes down to your sheer curiosity and desire to see what lies beyond the next set of stairs that really drives this game forward. This is informed largely by the fact that your playable guild is entirely populated by custom characters, and the game cannot assume very much about them except for their burning desire to press on.

All that being said, the game isn’t so faithful to its inspirations that it fails to do any level of storytelling. Around the third stratum of the dungeon, Etrian Odyssey begins to show its hand a little by seeding some significant foreshadowing and having more interesting story encounters, which eventually bear fruit in the later strata. It’s not a ton of story or anything, but what it lacks in word count it makes up for in ensuring every word counts, as well as using the environment itself to communicate some revelations with brutal but effective simplicity. This small tale is obviously far from perfect, in particular there are some character motivations that felt like they needed a little more expounding upon, but overall considering the particular writing constraints placed upon this title it’s difficult not to commend Etrian’s less-is-more approach to narrative. Besides, the sparseness of the narrative gives the player the freedom to make up backstories for the guild like the one I shared above, so if you’re into projecting stories onto your playable characters then this is a great game for it. (If this article gets 5,000 views, I’ll make my above excerpt into a legally distinct novel)

Gameplay in Etrian Odyssey begins unsurprisingly with the formation of a guild and populating it with adventures. You can hold up to 30 playable characters for whatever reasons you may need, but most players will probably stick to a core of five adventurers to meet the party limit. As mentioned before these characters are all blank slates, meaning you get to choose what they look like, what their names are, and what class they belong to. Whether you want to create totally original characters, delve into the maze with your family, recreate a favorite cast of other fictional characters (more or less), or some combination of these is all up to you, and this makes every player’s experience of the game personal to them in some way. One of the best things about this game’s party building is its limited selection of seven classes at the start. Many people bemoan the fact that the Ronin and Hexer classes are locked until much later into the game, and I do feel for the people who would rather have one or both through the whole game to save the trouble of slowing progress to grind them into fighting shape, however I actually consider this to be one of the game’s most important on-boarding tools. A smaller pool of playable classes ensures that a new player’s selection of 5 out of 7 is much more likely to include some of the most valuable classes in their long-term party. As someone who beat the game in high school on the DS with a very wonkily built team I can assure you that basically every combination will have enough synergy to get by, although you will probably regret not bringing a Medic, Protector, or especially both, because defense is very powerful in this game.

That sentiment will be especially apparent when you take your first steps into the labyrinth, because your very first set of encounters will probably match you with basic enemies that can totally rock your socks off. Playing on Picnic Mode turns the game into a one-hit kill simulator (which there is no shame in activating for grinding sessions) and Basic Mode is a sizable boost in your favor, but Expert Mode is in fact the game’s intended difficulty. Putting in the work and leveling up your characters does smooth out the experience a lot (and later on you can straight up break it with the right party builds), but Etrian Odyssey on the whole wants you to feel outmatched and sell the danger of its world. This does lead to a gameplay loop where sometimes you are only able to inch towards the next floor before getting your butt handed to you and you have to haul back to town (hopefully with an Ariadne Thread). While veteran players have come to enjoy this incremental thrill, it is definitely not a design friendly to those used to being able to sit down with games and make landmark process every session. The combat itself is very standard fare for the genre, although it can be more interesting depending on the build you go for. Having elemental damage on your team allows you to exploit weaknesses for bonus damage, and status effects can be game changing, especially the unique bind system which allows you to disable enemies’ special abilities by targeting the right body part (and they can do the same to you!).

Perhaps the best part of the game’s dungeon exploration design is its player controlled cartography system. The Yggdrasil Labyrinth is not a randomly generated space but rather a fixed maze, and the game engages the player with that space by forcing them to mark down its layout with a mapping tool. The game fills in the squares you step on automatically (though if you’re mad you can make this manual too) and the updated version gives you the option to automate walls (I like wall drawing personally), but no matter what you will be responsible for writing in annotations and placing doors, gathering points, secret shortcuts, and more. The game actually features a huge number of icons to choose from, but while some are obvious in their application most are general-looking enough to the point that the player will ultimately make up their own mnemonic code for certain elements of the dungeon. Which is awesome because two players might make maps with their own unique visual language, and that really puts into perspective the work that developers put into making prebuilt maps readable for a huge audience. I myself map out things carefully enough that I rarely make any risky mistakes, but online testimony about how a sloppy map got them killed really speaks to how much this mechanic adds to the adventure. With that said, perhaps the greatest weakness of the modern ports is this very mapping system as in order to make it work it has to take up half of your monitor, and while you can tuck it away to look at the environment more closely this is often less practical than having your guide on hand. This system was so fluid on the DS and was truly built around its hardware, and while I got used to the new system it just screams compromise. Hopefully any fresh entries in the series will iterate on this in a way to truly make the series at home on PC and console, but as it stands the transition to a single screen is fully functional but less naturally integrated than I’d like.

Of course there is one more element that ties navigation and combat together which is perhaps Etrian Odyssey’s most iconic feature: the Formido Oppugnatura Exsequens, or FOE as normal people call them. These guys appear within the game as fuzzy orbs of a scant variety of colors that move throughout the maze on set patterns or behaviors. Some patrol specific routes, some chase you if they notice you, and so on. If you collide with them, you enter combat, and FOEs are essentially minibosses for players without the strength to neutralize them. They even take steps around the maze as turns in combat pass, so if you’re fighting in their territory they might show up to clean your clock during a random encounter. FOEs are the main reason why mapping is so important, for if you know the area and figure out their behavior then there is usually a way to avoid them altogether, thus adding a layer of puzzle solving without the need for adding tacky brain non-teasers. Just the ever looming threat of sweet, sweet pain. There are a lot of different kinds of FOEs that pose different flavors of danger, so never let your guard down and enjoy the elation of getting to explore additional grounds of the floors when you do finally conquer them… at least until an in-game week later when they respawn.

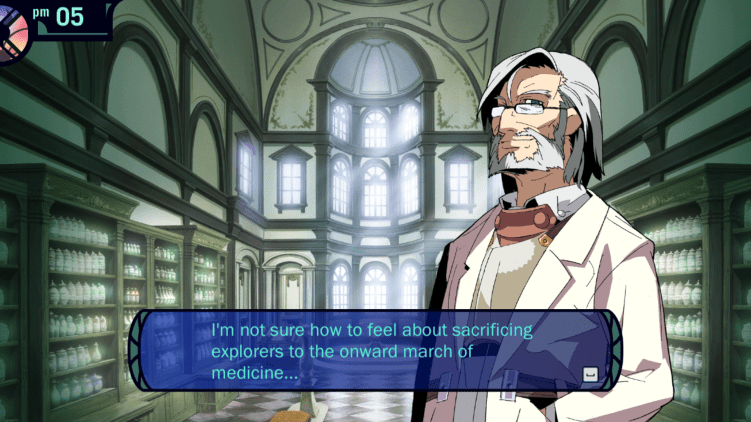

The town of Etria is the last major part of the game, and it basically functions as a very flavorful preparation menu. There’s an inn to restore your health and save progress, a clinic to revive downed party members and buy medicine, etcetera. The main twist on the normal RPG loop here is that the equipment shop updates its inventory as you sell them monster parts, and buying the equipment stocked this way is absolutely invaluable to getting stronger. The early game’s difficulty is definitely heightened by the competing needs of healing at the inn and clinic, upgrading your gear, and having an Ariadne Thread in your possession for a quick escape. Making trips into the labyrinth to collect monster parts and gathering point items does pay off in the long run, but knowing when to slow down and farm easy floors and when to push through and farm lucrative harder floors is a skill in itself. The game’s quest and mission system does help with this by offering a boost to your coffers and some free items, and I like how they are rewarding with respect to that tight economy. It’s also worth noting that while quests are typically added each time you reach a new floor, some quests ask for items found deeper than said floor you just reached, and I like how that feels less gamey than most other side quest systems. The demands of the townsfolk don’t just magically happen to line up with your party’s level of experience, and that feels so at home insofar as worldbuilding is concerned.

Presentation wise, I have a huge bias towards the game’s visual style from my younger years, but objectively it is very much what one would expect from a DS game. Animation in this game is saved exclusively for battle effects and a few elements of the dungeon like doors, and the rest is communicated through static images. The enemies are static pictures, your party is static pictures, the town is static pictures, and so forth. Thankfully, the artwork in the game is good and you can tell a lot of care was put into what the final art piece would be for every character. Each shopkeeper got a single frame to express themselves visually and the rest had to be communicated through text, but I really feel the warmth radiating from every one of them. The style itself is pretty soft in its presentation and gives everyone a sort of youthful energy which compliments the spirit of adventure.

The main issue with the style though comes in the form of the remaster’s unique portraits, which are newly drawn for the release but overall reflect the illustrator’s current style more than his old style. I’ve used one of each in the thumbnail for demonstrative purposes, and as you can see both pieces are good but the new makes little effort to blend in with the old. Perhaps once an artist’s style develops it’s not truly possible to draw in an old style, but some stylistic restraint to better blend with the older portraits would have been better. I’d also like to mention that while the texture of the 3D labyrinth was touched up for the remake, ultimately the visuals get pretty repetitive with each stratum, as there just aren’t as many environmental flourishes or interactables to break up the tree-walls. The final area of the main story serves as an exception here as while it is similarly repetitive in some respects, its novel elements are very powerful and make the environment quite impactful.

Musically speaking, Etrian Odyssey was originally composed with its retro aesthetic in mind and all of its soundtrack is synthesized. While ultimately I think the music was enhanced by the move to orchestrals in later installments, that doesn’t mean the original sound was bad by any means. How could it be when you’re billing the legendary Yuzo Koshiro? In particular I have to give props to the themes that play over each stratum while you walk through them. These pieces are disparate in how they set the tone for their varying environments, and yet most of them center on a heroic climax to reinforce the player’s resolve to overcome their surroundings, be they beautiful or hostile. The last two stratums of the main story stick out in this regard.

As for the moral wisdom of Etrian Odyssey, as one can expect there isn’t too much to glean from the game’s early stages outside of perhaps some discussions of perseverance and prudence in the face of great challenges. However, when the story picks up in the latter half of the game, a really interesting question lingers in the game’s overarching narrative that I find fascinating. The player starts to become increasingly more aware that reasons exist within the setting which would argue that the Yggdrasil Labyrinth should forever remain unsolved, and it brings forth a very simple question to the player: what could be worth pressing onwards for? Getting to the bottom of the maze eventually leads the player into conflicts with some pretty dark themes, and nothing less than a clear idea of why the Labyrinth is so important so conquer will suffice to redeem that conflict. In many ways a player’s reading of the whole game is directly affected by their ability to answer that question, and whether your guild is ultimately a fellowship of heroes or a band that committed grave injustices for the sake of reaching some trite endpoint will be a huge point of contention between different players.

Here in the real world we will hopefully never have to face the kind of impossible choices like the one featured in Etrian (especially since morally speaking we really must not do wrong in pursuit of right), but I think there’s a lot to be said for this idea of having a clear understanding of one’s purpose. As Catholics we thankfully have a fairly simple understanding of the ends we are striving for, but nonetheless we could all stop and ask the question “what I am pursuing by following this course?” from time to time. Without such a capacity for self reflection we may find ourselves unwittingly running towards a goal contrary to God’s Will, or try to accomplish that mission by the wrong means. We may be called to serve God in different ways, but ultimately the door we are seeking is a narrow one, so vigilance is key in all things. I myself feel guilty of this lack of self-reflection in many ways, but ultimately I hope this point inspires you to greater seeking of God’s will in your life, as I hope to amend that in my own as well.

In conclusion, Etrian Odyssey is a game with a very specific inspiration and design goal, and is also strongly a product of its time being the first entry in its series. Said identity makes it a difficult game to explain the appeal of, but striving to see the game for what it is reveals just how visionary it was, and why its legacy is not yet laid to rest. If you’re looking for a simple RPG with a strong focus on dungeon exploration and love a good challenge, then Etrian Odyssey will definitely charm you. It may not be for everyone, and furthermore its accessibility in terms of both its secondhand and primary market price points can compound the issue, but those who’ve tasted this labyrinth often find that nothing else quite compares.

Scoring: 76%

Gameplay: 4/5

Story: 4/5

Art and Graphics: 3/5

Music: 4/5

Replayability: 4/5

Morality/Parental Warnings

Etrian Odyssey takes place in a fantastical setting with various fantasy elements. The dungeon is filled with various monsters, although the vast majority of them have an animalistic or insectoid theme to them. Some of them are named after mythological figures and later in the game there are one or two FOEs that take the form of scantily-clad dryad-esque women, but on the whole nothing here is any scarier than “bear with massive claws”. Character design is arguably as modest as the player makes it since you have control over the looks of your party, but that doesn’t mean the option to venture into the labyrinth with a party of risque women isn’t available. The item shopkeeper and the bartender are also frequented characters with some revealing outfits. The ages of the characters are rather ambiguous, which may intensify the modesty issues present here for some players. Some player classes like Alchemist and Hexer have a magic theme to them, though this applies to the Hexer to a much greater degree with them being themed around cursing enemies. The furthest they go with this is a skill where the Hexer can make a scared monster commit suicide, although battle graphics are very primitive and neither this nor any other attack in the game is especially inappropriate to watch. Light use of foul language can accompany conversation with the guildmaster. Later in the game you are assigned a mission to exterminate a certain group within the labyrinth, which could come as a dark twist in an otherwise simple adventuring story. The post-game stratum features environments which are intended to come off as unnerving and gory.

I hope this article was worth the wait! If you enjoyed it or any other Catholic Game Reviews article, consider supporting us by becoming a Patron on our Patreon. For a modest donation each month, you can gain access to special updates, exclusive stickers, and even the right to request games to review every so often. Guild CGR is a passion project for everyone involved, so your continual donations help make it possible for our adventures to continue. Thank you very much for your generosity.