The world of board games is much vaster than many people give it credit for. While the number of different genres is eclipsed by that of video games due to the inherent limitations of physically moving and tracking different game elements, the industry nonetheless manages to find ways to make its smaller pool of possible mechanics represent a wide range of ideas. It is this ability to make simple mechanics feel thematically resonant which eventually made today’s game of enough interest to write a review of. But does its style belie a cheap and gilded construction, or will its craftsmanship be thorough enough to wow your group inside and out?

Designed by Shem Philips and SJ Macdonald and published by Garphil Games, Architects of the West Kingdom is a worker management board game released in 2018. Its premise involves a bunch of architects seeking to construct various buildings and earn the most respect from their king, while weighing the consequences of the various ways to reach that point. Players interact with the game through worker placement, hand management, accumulation of resources, disruption of opponents’ engines, and competing over limited chances to score points. Please note that this will be a review of just the base version of the game, as I haven’t really gotten into the habit of buying expansions due to the amount of physical space board games take up already.

Architects of the West Kingdom, like many of its contemporaries, scores player performance with one simple metric: collecting victory points. The most immediate means of accomplishing this is by playing building cards. These cards give you a set number of victory points when placed down, in addition to immediate and/or endgame bonus effects. To play these one must dedicate their workers to various locations around to board in order to gain various materials for paying the cards’ costs, from plentiful materials like clay to elusive materials like marble. You may also need to accumulate and spend silver coins to do things like hire apprentice cards, which in addition to having passive bonus effects feature icons necessary to build the more intricate structures. The other primary means of gaining points is by placing a building card under the bottom of the building deck and paying a relatively simple material cost to contribute to the construction of the cathedral, a central project available at all times. Doing so awards fewer points than most cards but offers a limited set of various random goodies, and reaching the highest tier is the single highest value thing in the game as far as victory points go. Both of these primary scoring actions are taken by claiming limited space at the guildhall, of which full occupation ends the game and signals the tallying process (made much simpler with the Garphill Games app). The cathedral additionally has limited spaces at each tier, meaning that only so many players can achieve the benefits of investing in it long term, and you can even block others’ cathedral progress just by hogging a tier alongside other players. These two stipulations reveal the first layer of the game’s tension, where time spent gathering resources for big plays leaves your opponent with time to potentially make plays of their own big or small, meaning you have to ensure that whatever you are working on will score you enough points to make up for building fewer projects overall.

If that were everything then the game would be mildly interesting, but the actual dynamics of gaining materials make this whole process fiercely competitive. Each worker you place on a location stays there, and whenever you place an additional worker in a location you gain a greater effect, such as a larger sum of wood or a wider selection of apprentices to choose from at no additional cost. This can get you crazy amounts of resources and decide entire games, but the whole dynamic changes when the town center is considered. By going to the town center, for a single silver a player can return all of their workers in an area to their supply, and capture the workers of enemy players along with them. Those workers are then able to be given to the guardhouse for a tidy return on your silver investment, and only then can players retrieve their captured workers back unless they opt to visit the guards early and pay a handsome sum. This creates an environment where you want to accumulate lots of materials and stack your workers to make it easier, but all it takes to change that is one opponent taking notice and opting to spend their turn setting you back considerably. You can also try timing your captures of popular areas to make as much money off your opponents as possible, or simply use it to scoop up your workers when you’re done with an area and save yourself headaches later. Despite how relatively solitary the actual act of working towards your score can feel in a vacuum, the pressure of capturing makes almost every moment of the game feel like a competition. Many other games achieve similar effects by making the spaces themselves limited resources, and there are a few mechanics that do feature limited spaces here too, but Architects manages to pull off the exact same feeling while encouraging a much more fun system of dogpiling spaces, all while avoiding a lot of the first move imbalances other games suffer from at times.

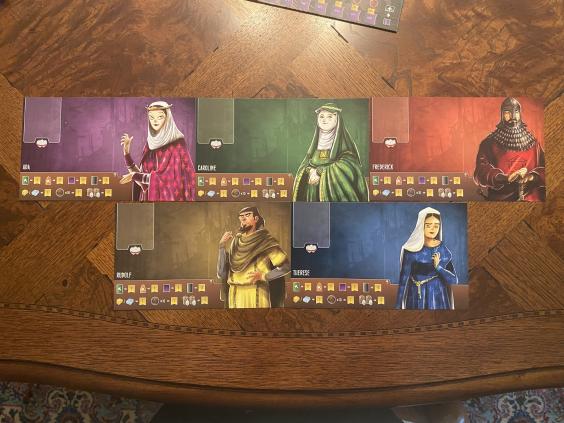

From here I’d like to go ahead and talk about the game’s presentation. Artistically speaking, Architects of the West Kingdom’s style is inherited from the North Sea trilogy of board games which has carried through the other two West Kingdom games, and will be there in the South Tigris series and whatever the East ends up being. Everything has this cartoonish exaggeration to it and overall has a rather hard-edged feeling at first blush. There was a little hesitation in me about how the artstyle might propagate stereotypes about how medieval civilization was supposedly full of dirty and unwashed people, but after a while I came to find it rather charming in how it embraces the rugged act of building up a civilization. Sure I think a softer aesthetic might better suit a game about constructing grand cities, but given that the choice was made to keep a consistent brand across four trilogies I think they’ve done a great job incorporating western Europe’s cultural sensibilities into that brand. The game board itself depicts the town with functional focus, but the little people painted in give it a spark of life that I can appreciate. Architects is also unique among the West Kingdom games as being the only one where the player’s selection of color is also the selection of a particular character. This feature is a purely practical matter in order to include a variant game mode where the character you have changes your starting resources and grants a unique passive, but selecting a particular architect to represent your actions in the world makes arguing over pawn colors way more fun, and I would have loved to see more superfluous character selection in Paladins and Viscounts.

You might have noticed that a lot of what I’ve had to say about the game’s presentation is wrapped up in functionality, which leads me to probably both the strongest and weakest aspect of the game’s design: how the game’s components minimize the amount of text in them as much as possible. Text is largely used to indicate flavorful stuff like the name of a location or the occupation of an apprentice, but many of the strictly mechanical aspects of the components are communicated through mnemonic symbols referring to different pieces and rules. This has the effect of making every card very pleasing to look at and leaves more room for the art to breathe, and while reading through the rules is vital to learning the game, it is once you understand its systems well that you really appreciate how easy it is to know what the consequences of specific cards are at a glance. The issue is that not every last rule has these kinds of reminders, so you will often crack open the rulebook to a section you wanted to check only to suddenly remember “oh yeah you can only have 5 apprentices hired total” or what have you. While Architects of the West Kingdom is actually much easier to play than you think once you see how it all fits together, there is nonetheless a learning curve to get there, and while the mnemonic design helps in this regard it is very easy to over rely on it and ultimately let a few rules slip under the table. Still, I can’t deny the ambition and execution of the text minimization, and come away from it more positive than negative.

Finally I want to go over one last mechanic which ties everything together and gives the game its thematic cohesion: the virtue track. Every player begins the game with their virtue score in the center (variant play notwithstanding) and various actions either raise or lower this score. Individual buildings and apprentices can affect your virtue when put into play, but there are also consistent ways of manipulating your virtue score. Working on the cathedral and donating supplies to the king’s storehouse, for example, will increase your virtue, and actions like taking the silver accumulated at the tax stand (the destination of a certain portion of silver paid for various actions) or taking an action at the black market (one of the only limited-space actions, which offers you a lot of ways to get rare and costly supplies on the cheap) will lower your virtue. Having a high virtue makes you lose the ability to use the black market but awards points at the end of the game, and a low virtue will prevent the cathedral from accepting your services and lose you points at the end of the game, but allows you to commit tax evasion and lessen the strain on your silver pool. The basic idea behind the system is that playing virtuously makes accomplishing your goals take longer, but by playing unvirtuous strategies you endure various penalties that you must make up for somehow, and it’s a neatly flexible system.

What has really stuck with me about the virtue system though was one game I played with TheGoodHoms, where I played full virtue and he played full scoundrel. We each managed to accomplish really great feats of architecture in our own fields and scored a ton of points, but when all was said and done I managed to beat out my brother by a single point. Now obviously we haven’t optimized our play or anything, but relatively speaking I find it striking that the player who strives for virtue also tends to be the player who ultimately comes out on top. Heck, in just about every game we’ve played so far, progress up the cathedral is often directly correlated to one’s position in the final ranking. In this regard Architects of the West Kingdom is a rare game that subtly teaches the player the value of taking the straight and narrow in order to win ultimate victory in the end, or at the very least teaches one to atone for engaging in bad behavior if they want to have any hope of victory. I can scarcely imagine many games more suited to an afternoon of friendly table politics among company that also wants something meaningful to chew on. As a Catholic I’ve never been overly interested in didactic game design because its lack of subtlety can make the experience into an education first and a game second, but Architects clearly shows that you can infuse a game with moral lessons without taking anything away from the dynamic of the game. And while it’s true that a player who eschews the moral high ground can still win, the long-term effort they have to put in to make up for their short term corner cutting nonetheless communicates a very distinct message about how the means are as important to scrutinize as the ends are.

In conclusion, Architects of the West Kingdom is a fascinating twist on worker placement games, with its emphasis on player politics and moral decision making alike make it one of the most memorable games I’ve ever played. Its learning curve can be a bit to overcome during your first round, but once you pass that hill then it becomes a game that’s quite easy to replay many times over thanks to some ingeniously streamlined design and various different strategies to try out. Building a kingdom that will truly be lasting requires the will to promote the virtue that shall sustain its people, be that a medieval civilization or the heavenly endpoint of our lives. Perhaps give it a thought while figuring out where your next worker is headed off to.

Score: 80%

Gameplay: 4/5

Art and Graphics: 4/5

Replayability: 4/5

Morality and Parental Warnings

For the most part, Architects of the West Kingdom is a fully appropriate game. The game features a morality system, consequently meaning that the player has the option to make morally dubious choices like hiring a swindler or a thief, building gambling houses or a seedy moneylender office, visiting the black market, or stealing from the tax stand. Each of these actions are properly penalized by the game however so the depiction of morality is overall quite reasonable. It is perhaps a little bit of a stretch to say that building a watchtower or a military keep should lower your morality based on precedent like Just War Theory, but I see where the designers were coming from. Beyond that, there isn’t much to say other than the Merchant and Trickster are wearing clothes that show a fair bit of skin around the chest, and the Dungeon card having a skeleton in it, but the depictions are so cartoonish that it’s far from anything traumatic or corrupting in my opinion.