The long running Trails series is undoubtedly one of the most special sagas in the JRPG genre. As one plays through the various games it is a delight to behold the ways its stories and combat systems iterate and expand over two decades of content, It has been known to take these steps slowly, but today’s title promised a bold step forward in its marketing, claiming to bear a new and innovative combat system as well as a more mature take on its world and characters. As the resident series expert who’s taken it upon himself to see just where this whole tale would go, I of course eagerly sank my teeth into this long-awaited new beginning to tell you all about it. It was a long 70 hour journey to the end of this road, but I’m finally ready to give my thoughts!

Developed by Nihon Falcom, published in the west by NIS America, and released on July 5th of 2024, The Legend of Heroes: Trails Through Daybreak is a modern Japanese roleplaying game available on PS4, PS5, Nintendo Switch, and Steam. Its premise involves an underworld contractor teaming up with a high school student to reclaim a technological legacy amidst the underbelly of a rising superpower nation. Players interact with the game through environmental exploration, character customization, turn-based and real-time combat systems, and a lot of cutscenes and dialogue reading. Please note that the Steam version of the game was used for this review.

Regarding this title’s place among the wider series, it is the eleventh mainline title and constitutes the start of a new arc. As with all games that start new arcs this does lend itself to being a decent on-boarding point for newer players, however unlike the army of reviewers who have emphasized Daybreak as a starting point I do personally think that it is not the best place to begin from. This is because the game features a very sizable amount returning characters, in fact the official website displays about a half dozen of them. While other starting games like Trails from Zero also had some returning faces, they weren’t nearly as numerous or frequent as Daybreak’s ensemble, and their market share of screen time would definitely be lost on beginners. I am of course not here to dissuade you from beginning here if you are so determined, as insisting that someone play ten lengthy games before the one that they were interested in would likely be burnout city, but you do have to accept that not everything is going to make sense right away, especially in regards to terminology.

The story of Trails Through Daybreak takes place about a year and a half after the events of Trails Into Reverie, and is set in the Calvard Republic. The protagonist is a young adult by the name of Van Arkride who lives in the capital city of Edith and works as a spriggan, which can best be described as a fixer who tackles commissions either too complicated or too illegal for civil servants to handle. The game opens with a highschool student by the name of Agnès Claudel hiring Van to help her track down a pocket watch-like orbment, one of eight Genesis devices created by the father of the Orbal Revolution and great-grandfather of Agnès. The hunt for the first of these brings the two into contact with the terrifying mafia Almata as well as a mysterious power dormant in Van called the Grendel. Sensing great danger Mr. Arkride opts to assist Ms. Claudel over the long-term in her hunt for the other seven Geneses, which leads the two of them into an investigation spanning most of the Republic, in a tale fraught with conflict.

Based on my own personal taste in Trails games I wholly expected Daybreak to win me over with a slower paced and character driven dive into the new setting and cast, but having come out the other side I can quite confidently say that for a number of reasons that this is among the worst Trails narratives to date. The main plot is driven entirely by the hunt for the Genesis macguffins, to the point where the one Agnès carries around literally lights up to let her know that she needs to beg Van to accept some job or other that will lead them to another Genesis. The vague nature of the Geneses also leads to them being perfect plot devices for literally anything the story wants to do, and while Daybreak doesn’t do this uniquely it does feel the most blatant considering the focus is mostly on these baubles. The many characters you meet along the way are also quite static and don’t change much over the story, meaning this is another cast of characters that you pretty much either love or hate based on your first impressions of them. Out of the main cast I really only felt attached to Quatre and Ferida, with the other characters either not getting enough screen time or are just plain uninteresting. The extended cast similarly struggles to find meaningful highlights outside of some returning characters, and even then not all of those were handled as well as they perhaps should have been. Only the villain Melchior of the Thorns ultimately left a big impression on me, as amid a sea of middling protagonists and painfully bland villains he embodies the essence of a character that is irredeemable in every way possible and yet leans into it so hard that you can’t help but love watching him (helped by some absolutely killer English voiceover).

If I had to pinpoint one issue with the story that truly causes it to lose its way it would have to be Van Arkride himself, as everything about him feels profoundly fake and childish. The main advertised element of “increased maturity” that Daybreak flaunted was that Van was going to be a morally gray sort of character who rides the line of legality to achieve his goals, and for me that would be fine if this background was used as an opportunity to grow into a more virtuous person that walks more in the light of justice (perhaps through the positive influence of Ms. Claudel) or otherwise leave us with a message that teaches us the danger of riding that line. Unfortunately this never happens, and we’re left with a story that does nothing but adulate Van at every turn no matter how much he acts like a conniving lowlife. This is extremely indulgent and not at all healthy, and I’ll explain why this is in the wisdom section of the review. For now though I’d like to express that what makes Van feel so fake is that his profession of ‘spriggan’ comes across as a massive contrivance to justify a ton of deception, entrapment, assault, working with criminal organizations, blackmail, and more, without actually getting him into trouble. The job of ‘bracer’, as a point of reference, is also a largely fantastical job with no real world equivalent but the Sky games go to great lengths in establishing the Bracer Guild as a sprawling international network that serves a logical purpose within the world of Zemuria. Compared to that, Van is the only spriggan we meet over the course of the entire story and there’s no bar by which we can measure what a spriggan can and can’t or should and shouldn’t do, to the point where Van might as well be the only spriggan on the entire continent. The crap this guy pulls with no real consequence is staggering, and I simply couldn’t buy into his fantasy at all.

All of this is to say that the story of Trails Through Daybreak is impressively bad, and I haven’t even gone over some of the other problems like how some of its chapters have terrible pacing, its awful treatment of women (HELLO CHAPTER 3, GO TO PERVERT JAIL), and how bland Calvard as a setting is. There is of course one infamous topic of discussion surrounding this game that needs examination though, because in addition to everything else it includes modern racial politics as part of its narrative. This is way too touchy of a subject to include in the main body of an article on a website primarily aimed at serving families as a whole, so I will address this in a special feature to be released soon. Spoilers will be on the table there, and I don’t recommend reading it unless you’re seventeen years old or more.

Regarding the title’s gameplay, this is where Daybreak delivers significantly more on its promises of change. The combat system is divided into an action combat phase and a turn-based phase as opposed to the purely turn-based system of old. The action combat phase in one sense can be seen as a simple extension of the previous systems where smacking an enemy in the overworld will grant you an advantage, but Daybreak offers the player the ability to stay in this mode of combat and defeat enemies without needing to go turn-based at all. The game certainly is not designed for the action combat to completely replace the turn-based system, flagged by the great simplicity of the action movesets compared to the wealth of options in the turn-based mode, lower exp bonuses in action combat, and a lack of action combat in boss fights at all. On the whole though it serves as a good middle ground between choosing to do a full turn-based encounter and ignoring the enemies in favor of simply advancing the story. Most of the time you’ll be using this action system to put the enemy into a stun state and make switching to turn-based combat much easier.

As for the turn-based combat itself, it’s the same position-heavy Arts and Crafts system we’ve seen since the earliest days of the series, but a few key changes give it a flavor all its own. For one thing the move action has been completely removed, and now combatants are free to reposition themselves as much as they want no matter what action they ultimately choose to take. Aside from being a very flexible tool that keeps the pace of a battle going, this opened up design space for Crafts that check character position relative to the enemies for bonus damage. It’s a very impactful change, and the numbers you can achieve by engaging with the system such as Aaron’s back hit bonus on Falcon Talons are extremely satisfying. Speaking of positions, the ARCUS Links from the previous five entries have been changed into SCLM Links, which provide many of the same benefits like follow-up attacks and Arts boosting with the condition that the characters stand right next to each other in order to trigger. This arguably makes positioning more important than ever before, as you have to weigh the risk of bunching your characters tightly together against the reward of increased dps, and overall just zeroes in on the core of what makes Trails combat so engaging.

The last major change to turn-based combat is the S-Boost system, which is a resource that characters can consume for increased stats and special effects based on the Holo-Core (basically Master Quartz) they have equipped as well as being the means by which S-Crafts are primarily accessed. This mechanic forms the foundation of each character’s unique playstyle and allows you to formulate strategies that invariably become your win condition. For instance by equipping Van with Mare – Law to increase his survivability and taking advantage of the Hate Up status, he was able to run to the other side of the battle field and tank enemy attacks while the remaining party members focused on bursting down the enemies. This system does have its silly exploits though, as S-Crafts are not only quite easy to pull off but also increase your maximum S-Boost gauge, leading to a vicious cycle where using your most powerful moves makes it easier to use them again.

I also would be remiss if I didn’t mention the new defensive shield mechanic that allows you to effectively add a temporary bar of HP over your normal HP to protect you from attacks, and the fact that this mechanic is accessible through Crafts is supremely cheesy. Angès’ Jibril Guard is perhaps a little underwhelming when you consider you can just boost and use her S-Craft for 30 CP more, but Risette’s Cobalt Curtain increases your survivability by an absurd amount considering its low cost and Quatre’s Laplace Code is borderline cheating against any fight that doesn’t feature All Cancel. All that aside though, combat in Trails Through Daybreak is probably the best the series has ever been thanks to smart iterations that really lean into the series’ strengths while offering time-saving solutions to potential repetitiousness.

Orbment customization in this title is actually among the series’s most technical iterations, returning to its roots and yet reimagining its purpose in a way thoroughly tied to the modern system. The new XIPHA orbments are divided into four lines, most with four quartz slots each but often at least one line having just three. The quartz gives not only the stats and passives written in their names and descriptions but also elemental values, which are added up to determine passive effects depending on the line being calculated. Most of these abilities revolve around elemental damage such as boosting specific elements of Arts or adding elemental damage to physical skills, and later into the game you can assemble more generic powerful abilities like dealing extra damage after casting an Art or executing your enemies when they reach certain health thresholds. These passives are activated randomly, but S-Boosting a character increases the odds of their activation with double S-Boosting often guaranteeing them. This system is passive enough that you can spend most of the game simply adding in the quartz with the stats you want and be just fine, but it’s worth researching the code behind the stronger abilities in the late game to really push your power to the point where it needs to be, especially for the EX Line. In exchange for this more involved quartz system, Arts have been relegated to their own subsystem called Arts Drivers which determine your character’s available Arts in a very plug-and-play manner. Additional plug-ins may be purchased to round out the more specialized Arts-Drivers, but on the whole it’s much less easy to make a fully dedicated Arts character as self-sufficient as they used to be.

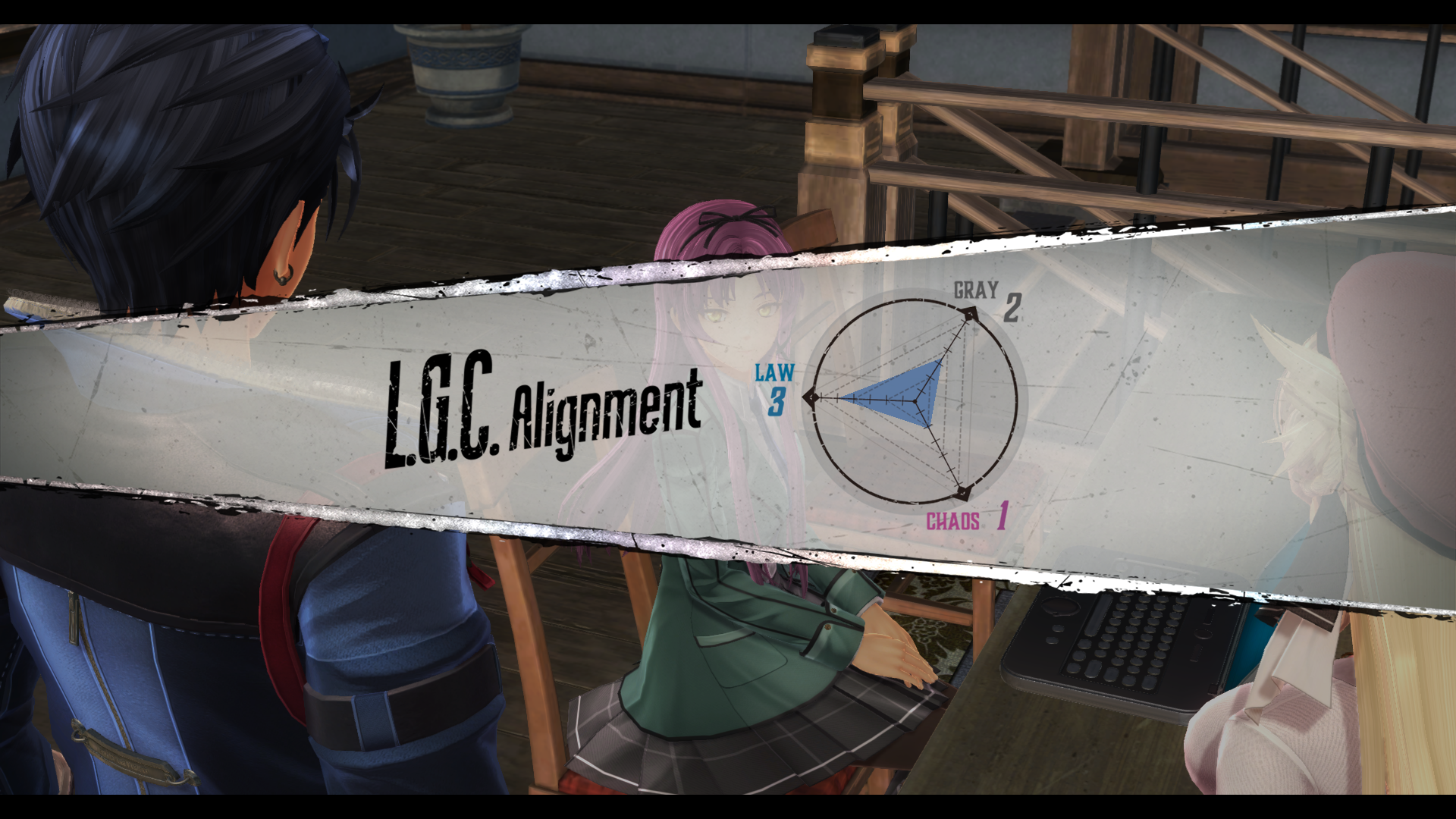

As for the exploration portions of the game, it remains relatively unchanged from the previous titles. You’re still taking on requests for side missions, moving between quest markers to advance the story, talking to NPCs, hunting for chests, the whole nine yards. The combat system changes make it easier to ignore enemies and swipe chests from under their noses, but it’s not like you couldn’t do that before. If anything the greatest change that came about in exploration is the alignment system, as clearing side quests as well as making choices during both side and main quests will earn Van points towards Law, Grey, and Chaos. At first I was very intrigued by this system as perhaps it was an opportunity for me to steer the course of the main story in a direction that would lead to the character growth I wanted out of Van, but unfortunately it ultimately wound up being a useless gimmick. The most significant this system ever gets is determining your allies for the duration of chapter 5, which while neat doesn’t lead to any long term consequences. Perhaps any true effect on the story was maybe a bit much to hope for considering the wide scope of the Trails project as a whole, and giving players that level of control over the characters’ development has already been noted as a long-term issue for Lloyd and Rean’s love lives, but at that point why bother with all this alignment nonsense if you’re going to have the story retake control of Van’s characterization by the end of it anyways? It’s simply a shallow way of encouraging replay value, and many of the most important decisions related to Almata are, without spoilers, completely undercut and muddied for the sake of gameplay.

As for the game’s graphics, Trails Through Daybreak is Falcom’s first full run of the in-house engine which was teased during climatic cutscenes in Trails into Reverie. After having spent the full duration of the game with this new engine, on balance I don’t think the raw graphical displays are truly remarkable as most of the character models and environments are about on-par with what we saw in the previous three games. This is a studio that runs on fairly modest budgets after all, so they really don’t have the money to push this side of the presentation much. Where the graphics truly improve is in the animation pacing, as there is a notable step up in quality both in the animations themselves and the cinematic direction. Ever since Cold Steel III the games have been trending in this direction, but I think Daybreak manages to push its combat animations to a new level, to the point where I didn’t start skipping battle animations until the finale. One of the stated goals by the developers was to cut down on the amount of time it takes to resolve combat, and their animation directors deserve a ton of credit for this even considering the conveniences of the new hybrid combat system. The lower stakes talking cutscenes are still as jank as ever, but really that’s just par for the course. Unfortunately for the musical side of things, the game’s soundtrack stands out as one of the most forgettable in the whole series. With the exception of a few late game tracks from the final dungeon it was hard to really identify any portions of the soundtrack that stood out to me, which is rare for a Trails game. Even Sky the 3rd’s relatively subdued soundtrack at least fit the reflective nature of that story and had Overdosing Heavenly Bliss, but Daybreak neither has a soundtrack prominent enough to match the action-packed setpieces it wants to have nor does it even have a song I actively burn to listen to again. There’s just not much to say about it, and I hope they can improve for next time.

Lastly, as for what we can learn from this title in a moral sense… you can’t. The foundational main theme of the entire story is Van’s role as an inbetween for the dark and light sides of society and how the people around him learn from interacting with his perspective. This is all based on the modern notion that good and evil aren’t usually clear concepts and there needs to be a ton of leeway given to those who operate in the gray area, and today I want to dive into that very concept.

From a pure human perspective on things, I do agree that knowing what the right thing to do can be difficult because we are all clouded by our personal biases unique to our experiences, the limited scope of our knowledge and understanding, and because of our tendency to abandon justice for the sake of selfish benefit (better known as sinfulness). However, we as Catholics know that God in His Omniscience is bound by none of those limitations, and if we are to hold that He knows the truth of all things then it stands to reason that He knows the right and wrong thing to do in any given situation. When you consider this key fact, the gray area thus reveals itself to be nothing more than an intellectual illusion that humanity constructs to help rationalize our doubts whenever the morality of a situation is too difficult for us to comprehend.

The demarcation of black and white is always there even when we can’t perceive it, and we have a responsibility to choose the good to the best of our ability. I believe that God in His perfect Love and Wisdom recognizes the great challenge we face in this and will show mercy to those who stumble into evil because it looked gray from their perspective and they simply made a wrong choice in the moment, but I think this comes with the expectation that we avoid even the gray almost as much as the black and strive to stay in the white. To live in the gray is to become desensitized to the true colors of the world, and it could end up warping your perspective until everything seems gray and you commit terrible injustices you never knew you were capable of.

I am of course not saying we shouldn’t risk entering that which we call “the gray area” at all because the white can and does truly exist in that space too, and it would be terrible if we did not chase the good out of a paralyzing fear of making mistakes. But we mustn’t allow ourselves to become self-deluded lowlifes the way Van has, and we certainly shouldn’t act like the other characters in the story and laud him for his “deep” and “mature” perspective. As it is written: “… God is light, and in Him there is no darkness. If we say that we have fellowship with Him, and walk in darkness, we lie, and do not [do] the truth. But if we walk in the light, as He also is in the light, we have fellowship one with another, and the blood of Jesus Chist His Son cleanseth us from all sin.” (1 St. John 1:5-7, Douay-Rheims Ver.)

In conclusion, Trails Through Daybreak very comfortably lands as my least favorite Trails title to date. While I believe it’s not objectively the worst one as the improvements to the combat and visuals do deserve some credit, the story being totally morally bankrupt and lacking in quality deals such a major blow to it that I can only say that it’s barely not the worst one. This game, more than any other in the series, is to me a title that the Trails superfan is obligated to play simply to witness the complete scope of the overarching story, and absolutely useless to everyone else. If you’ve never played a game in the series before, you will only enjoy this title if you relish in the idea of a game that balks at distinctions of right and wrong (which I would hope my reader base is not), and I highly recommend starting with a different arc. Trails Through Daybreak II has been announced for next year at the time of this writing, and while I still intend to cover it if I am able to I can’t say I’m very hopeful as of now. How ironic that the game with dawn in its name seems to be heralding dark days ahead for the series…

Scoring: 56%

Gameplay: 4/5

Story: 1/5

Art and Graphics: 5/5

Music: 2/5

Replayability: 2/5

Morality/Parental Warnings

Trails Through Daybreak takes place in a fantasy world steeped in supernatural themes. The orbal technology that much of the game’s world revolves around effectively runs on magical energies and this is sometimes accompanied by magic circle imagery. Various items, monsters and organizations regularly draw upon real world religions and mythologies for their names, although their distinction from said inspirations are quite obvious. The most pressing inclusion in this regard is the appearance of “devils” and “archdemons” as fightable monsters, but there are other more subtle inclusions like the black ops heretic hunters of the Septian Church having the very unfortunate name of Iscariot. Said Church is the primary fantasy religion of the entire series, but it is otherwise a monotheistic force for justice so it’s not terribly scandalous. It’s also implied the power of the Grendel has some sort of demonic element, and the living AI Mare is capable of possessing people. Combat in the game features fighting with melee weapons, guns, spells and more but blood is rarely present. Blood does get portrayed pretty explicitly in some story scenes however, including a scene where a villain stabs himself in full view of the camera (suicidal acts and contemplation are also featured in the game). The game’s quests also feature the protagonist engaging in, either depending on player choice or as a matter of course, blackmail, lying, deception, smuggling, assault, subversion of lawful authority, entrapment, visiting adult establishments, and even murder in very rare cases, among other things which I probably didn’t see because this game has a ton of content which you can’t see all of in one go. Naturally in order to make the protagonist look more heroic the primary antagonist in Almata is especially heinous, featuring an executive line up filled with psychopaths and nihilists whose crimes go all the way to nuclear terrorism. The game also features themes of racial politics that are handled quite badly, which I will discuss extensively in a separate article. I will say though that the game basically associates any and all conservative thoughts on the part of white people (and yes WHITE is the term they use in-game, even though no other races are referenced directly like this) as implicitly racist and supremacist, to the point where the story effectively condones subtle prejudices against them.

Ferida Al-Fayed is a child soldier which the party hires without much serious objection, and her outfit probably should be more modest considering she’s thirteen. Aaron Wei’s day job before joining Arkride Solutions was as a theater dancer who crossdresses for his performances. Quatre’s chest has deliberately never been shown on screen, and while there could be any number of explanations to reveal in Daybreak II I can’t discount the idea of transexual themes being involved. As a survivor of the D∴G Cult (child experimenting devil-worshippers from previous titles) this would almost necessarily cast this secret as a negative thing though, and when Van asks Quatre “What pronouns should I use for you” everyone else in the room finds this gesture deeply offensive. A couple of characters are all but stated to be homosexual, most of whom are villains but the game does try to come off as non-judgemental about it. The info broker Bermotti in particular speaks in a lot of homoerotic innuendo and dresses very effeminately, though most of the characters who know him don’t take these aspects of him seriously. Sexualization of women is absolutely rampant even by low-brow anime game standards, with many of the major characters wearing revealing outfits at least once if not constantly, and there is a pole-dancing bar scene in the middle of Chapter 3. Chapter 3 itself is centered around a film festival helmed by Salvatore Gotti, and the fact the crowning production of the festival is called The Carnal Cavalcade should tell you everything you need to know about him and his movies (the Cavalcade is a parade featuring dancing in sexy outfits). There are also scenes at saunas and hot springs that feature the cast in bathing towels. Foul language is quite prevalent in the game’s script, as well as rather explicit and base reference to acts of fornication. They even include words so strong they have to bleep them for the sake of keeping the rating down.