In our second entry of the Terminal Typology series, we’ll discuss various Christian themes present within Final Fantasy II. Such an exploration is not possible without discussing details of the story, so spoilers will abound. Please note it’s not so much our contention that the themes are present intentionally, but rather because the Final Fantasy games are good, contain truth, and are beautiful – and those transcendents can lead us to God. Essentially, we hope to nerd out over Final Fantasy II and follow these words of St. Augustine:

“…when anything pleases us because of You, You are what pleases us in that thing, and when by Your Spirit something pleases us, it pleases You in us.” (Confessions, Book 13, XXXI).

For the first entry in the series, discussing the original title, please see here.

A darker tale…

Final Fantasy II opens on a grim note – we’re told that the peace long enjoyed by the denizens of Final Fantasy II’s world is over. We see city after city laid waste as the Emperor of Palamecia looses demonic hordes upon the world in a bloody bid for world domination. The kingdom of Fynn attempts to resist, but Palamecia’s response nearly destroys them. A small remnant from Fynn is able to escape and gathers in the town of Altair, where they form a new rebellion under the sign of the “Wild Rose”.

The player characters – youths from Fynn named Firion, Maria, Guy, and Leon – are among the escapees, but their flight is arrested by pursuing Palamecian soldiers. The quartet is defeated in battle and subsequently separated. Only Firion, Maria, and Guy find safety, later awaking in the care of Fynn’s princess, Hilda, and Minwu, a wizard who lends his magic to the rebellion. Healed by Minwu’s ministrations, the youths implore Hilda to allow them to fight for the Wild Rose – in part to search for the missing Leon.

It’s worth pausing here, as a few important types can be identified right as the game begins. Our first experience with the game’s world is to be defeated by its evil; a defeat remedied by a healing ritual performed by a priest-figure in the presence of a royal woman. If we consider the language we often use to describe the Church: “Holy Mother Church” or “the bride of Christ”, then it does not seem to me too much of a stretch to read this event as a type of Baptism. We are marred by the brokenness of Original Sin as we enter our world, and so too does our life’s quest only truly initiate when we are healed through the waters of Baptism.

Furthermore, Hilda’s typification of the Church isn’t limited simply to a superficial connection to words we use when referring to it. Hilda becomes a constant presence in our path through the game. The Wild Rose rebellion is not centralized in a particular location – it operates wherever she happens to be, lending it a pilgrim quality until she is restored as the queen of Fynn. She sends the player characters on their missions, and it is to her that they always return. As I see it, these repeated encounters with Hilda point to the way in which we encounter God’s grace through the Church, and how we should respond to it.

A striking feature of Final Fantasy II‘s tale is that it is not one of a band of plucky teenagers taking it upon themselves to save the world, though save it they ultimately do. Instead, these heroes are operating at the behest of a higher authority. When Firion, Maria, and Guy are restored to health, they wish to satisfy their youthful zeal and belligerence as soon as possible by taking up arms in support of the rebellion. However, they subordinate their wills to Hilda’s, as Hilda knows there are tasks for which they are better suited, and which will prepare them for greater and greater responsibilities. This is a message that aligns well with something Scripture reminds us of again and again – whenever we believe we know better than God what is right for us to do, we harm ourselves and those around us. This is essentially the story of the Fall, it’s why Moses is denied entry to the Promised Land, it’s the reason Saul is punished for his impatience with Samuel, and more. The story of Jonah, however, is particularly apt when considering the story of Final Fantasy II, as we’ll see when considering the nature of the game’s quests.

First, since the Wild Roses are outmatched by the strength of their foes’ weaponry, the youths are tasked with securing a source of a metal called mythril. With mythril, the Wild Roses will be able to forge armaments on par with Palamecia. Unfortunately, the only reliable source is a Palamecian-controlled mine far to the north of Altair. The heroes successfully infiltrate the mine and obtain the mythril, only to find that Palamecia has nearly completed a new weapon – the flying warship “Dreadnought”.

The Wild Roses then hatch a plan to interfere with the construction of the Dreadnought. Our young heroes sneak into a Palamecian-occupied town, but their efforts come to nothing. They’re intercepted before they can stop the completion of the warship, Hilda is kidnapped, and the Emperor uses the Dreadnought to cut a worldwide swath of destruction. Firion, Maria, and Guy then set out to rescue Hilda from within the Dreadnought itself, where she is held captive.

Glossing over quite a few details, the heroes destroy the Dreadnought and ultimately save Hilda from within the Palamecian capital itself. Time and again, we see that our heroes’ mission is to operate amongst great danger, but not be consumed by it. We, too, are given this same directive. We must be in the world, but not of the world. (John 17:14-16). And if these metaphorical entries into the belly-of-the-beast weren’t enough…one mission actually involves the escape from a Leviathan’s stomach.

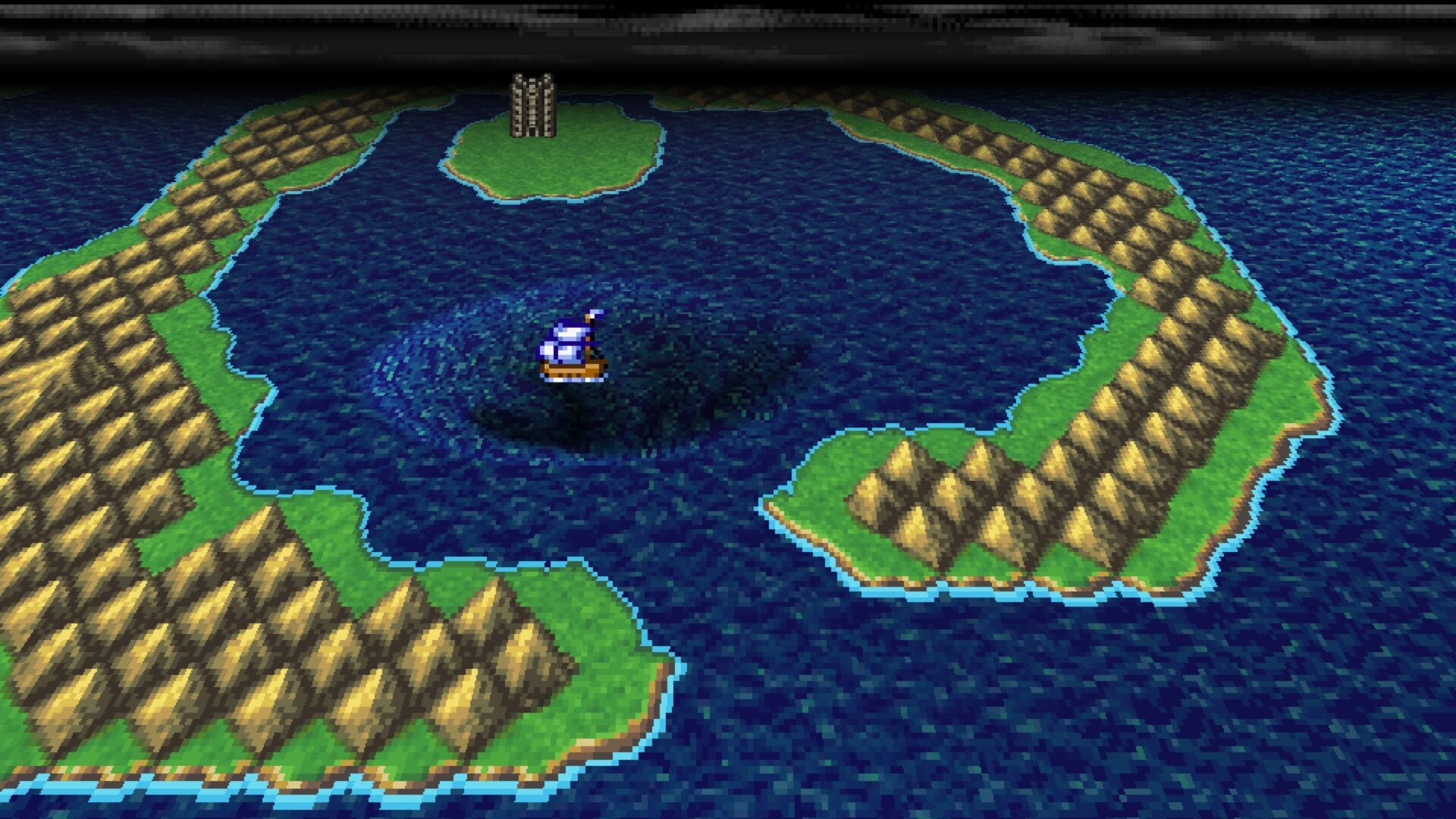

Before the heroes can launch their final assault against the Emperor, they must again obtain a power equal to the task. However, where before they sought a weapon of physical power, they now chase a rumor of the ultimate magical power, a spell aptly named “Ultima”. They learn that ancient mages weaved Ultima to banish the lord of Hell, but then hid it away for fear that the spell would later be misused. Ultima’s spellbook was sealed atop a secluded tower on an island protected by the sea serpent Leviathan.

The image of a boat caught in a storm, along with the presence of a great fish, naturally brings up associations with Jonah, and there are indeed some interesting contrasts with that story. The analogy is not perfect – in Jonah’s case, God sends the fish to get Jonah where he should be. In Final Fantasy II, Leviathan is instead an obstacle, even if it is designed as a test. The test appears to require only timing and physical strength, as there’s nothing to suggest that the Emperor couldn’t also have obtained the spell, had he chosen to search for it. However, we could surmise that the Emperor believes that nothing exceeds his own power and discounts the existence of Ultima as a useless legend, while the heroes have no qualms about seeking an ancient authority. Speculation aside, and considering video game quest design as a whole, there are still some valuable lessons to be drawn from the episode.

Jonah has the capacity to resist his mission, and when he does, he and his shipmates are nearly swallowed by chaotic sea waters. Given the design of Final Fantasy II, our player characters cannot be given this choice, but this design limitation can be read in a couple ways. In one sense, while internally to the narrative the characters may have no choice, we have the choice to participate in the story or not. If we do not operate within the parameters of the game’s design, and continue to play it, its world will forever be unsaved. A similar dynamic is at work in our own lives – we are only truly free to the extent we participate with God’s will for us. If we do choose to complete the quest, the heroes’ conquering of the Leviathan and return from the depths can be seen as imaging God’s power over the primordial watery chaos and as a metaphor of Christ’s resurrection.

Once they’ve obtained Ultima, Firion, Maria, and Guy prepare themselves for the final confrontation with the Emperor. Again glossing over a few plot set-pieces, the heroes enter the Emperor’s stronghold, confront him, and defeat him. All seems well with the world, and Fynn naturally throws a huge celebration…which is interrupted by the unwelcome news that one of the Emperor’s dark knights has taken up his mantle and adopted his violent tendencies.

Our player characters are tasked with returning to Palamecia to defeat its new lord, but are met with a few surprises. For one, the new ruler’s identity is Leon himself, who had apparently been inducted into the order of the Emperor’s knights. Secondly, they find that the previous Emperor is not truly gone, but rather has gained power from his infernal experiences and has returned to retake his throne and resume his ambitions ostensibly as an instrument of the lord of Hell (which, based on a comment from one of your compatriots, he likely always was. Background details are slim by necessity in NES games). Keen readers who have heard a story before will not be surprised to learn that our heroes, with Leon’s help, journey deep into the Emperor’s hellish castle itself, Pandaemonium, and defeat the evil Emperor again once and for all. They may, however, be surprised at Leon’s decisions in the celebration that follows.

Leon, wounded by his association with Palamecia and its crimes, chooses to leave Fynn rather than stay with his friends who’ve forgiven him. We’re never told why Leon ended up a dark knight of Palamecia, but it’s worth speculation particularly in light of our discussion of how we must train ourselves to conform our wills to God’s.

Was Leon abducted and pressed into service by the soldiers he encountered with his friends when fleeing Fynn? Perhaps, but even so, no one forced him to rise through the ranks of the Palamecian war machine. Leon may have been forcibly taken from his friends and his home, but he voluntarily adopted the ideology and justifications of his captors. Is this not an object lesson for us? How easy it is for us to hide or let go of our principles when surrounded by those who do not share them. How easy it can be for us to adopt the conventional wisdom if it’s expedient for our personal interests or simply makes life a little more comfortable. Leon, in contrast to his brethren, did not listen to a higher voice, and as a consequence became indistinguishable from the enemy. It is fortunate he returned to his senses, but understandable that he would feel a need to do penance before reintegrating himself in Fynn.

There are other praiseworthy elements of Final Fantasy II, but it was the concept of mission, and how we choose to carry it out that stood out to me. I’m probably not in a position to become some edgy dark knight lord of a vast empire (though I dig the armor), but I can’t help but find relatable elements in Leon’s descent. It’s easy to fall into a spiritual rut, mistakenly believing I should have some grander mission when I’ve already been given roles of incredible importance. If I ever neglect my duties as disciple, husband, or father, considering them to be mundane, what would I be doing other than constructing a god I want to listen to, rather than listening to the One Who Is?

In the final analysis, we either are truly seeking after God, or we are listening to ourselves. As in Isaiah 50: 10, we all in some sense walk in darkness, but we make a choice to rely upon God, or to stumble through with lights of our own making. In Final Fantasy II, we can see this difference metaphorically represented through the stark differences between the heroes and villains. Only with patience, discipline, and docility, can we train ourselves to follow God’s will, and on this score, Firion, Maria, and Guy can serve as good examples.

Typology Terminus (II)

Thanks again for indulging in some Final Fantasy analysis. If you enjoyed this, please look forward to the next entry, covering the last NES game, Final Fantasy III.

Additional Links

If you want to go deeper into the idea of mission, how we should respond to God’s call, or the themes in the story of Jonah (and more), please see this address given by Bishop Barron.

(Or here, for a more bite-sized version.)