If I had a nickel for every murder-mystery video game I’ve played set near the Reformation, I’d have two nickels. Which isn’t a lot, but it’s weird that it’s happened twice! Misericorde is a visual novel set in an English abbey, circa the 1480’s – you follow the story of Sister Hedwig, an anchoress who, under orders from her Superior, is broken out of her cell and tasked with investigating a murder. As the only one with an ironclad alibi, the Superior can only trust you. But this abbey is far from your normal abbey, and this story will only get stranger.

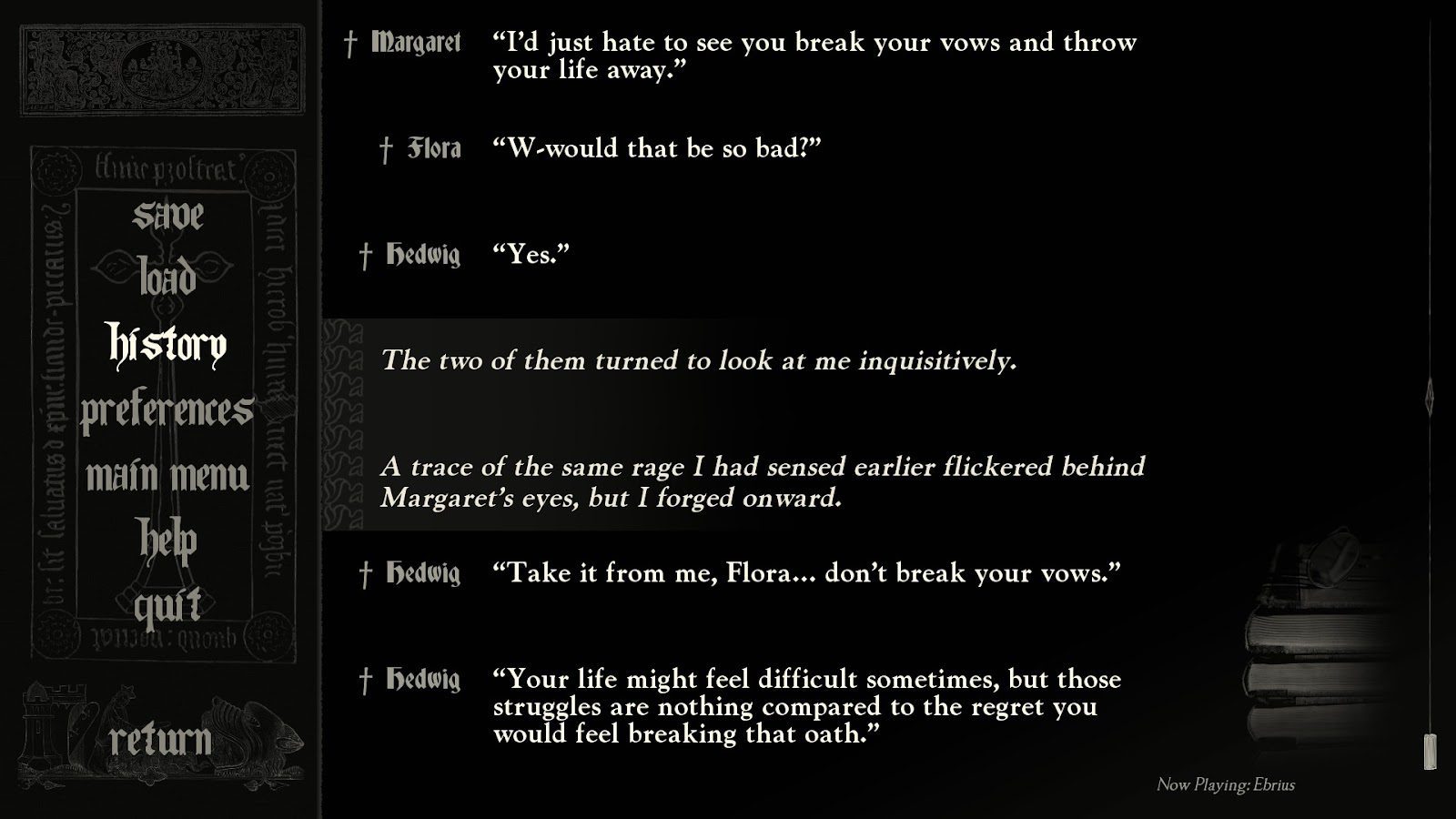

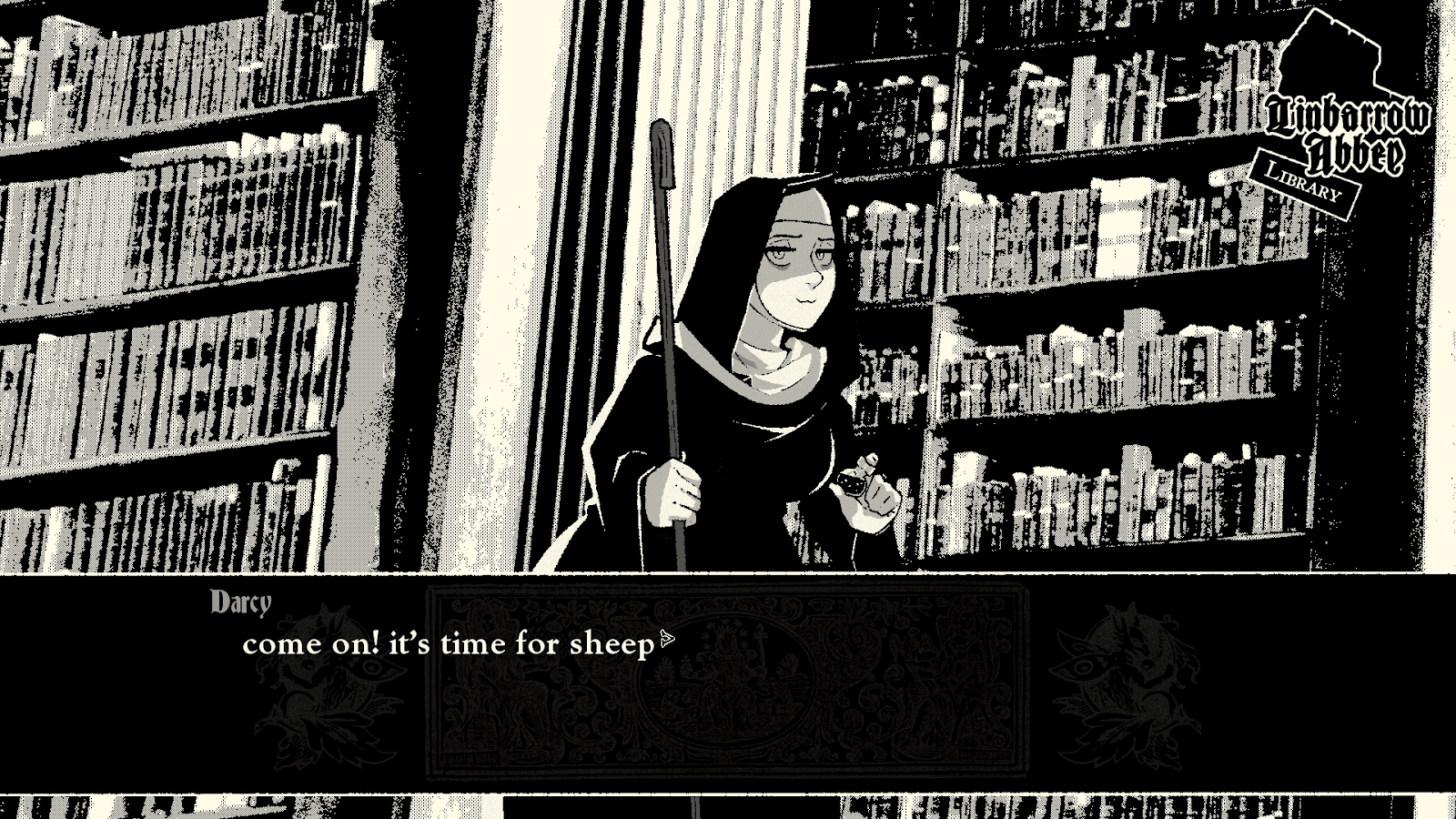

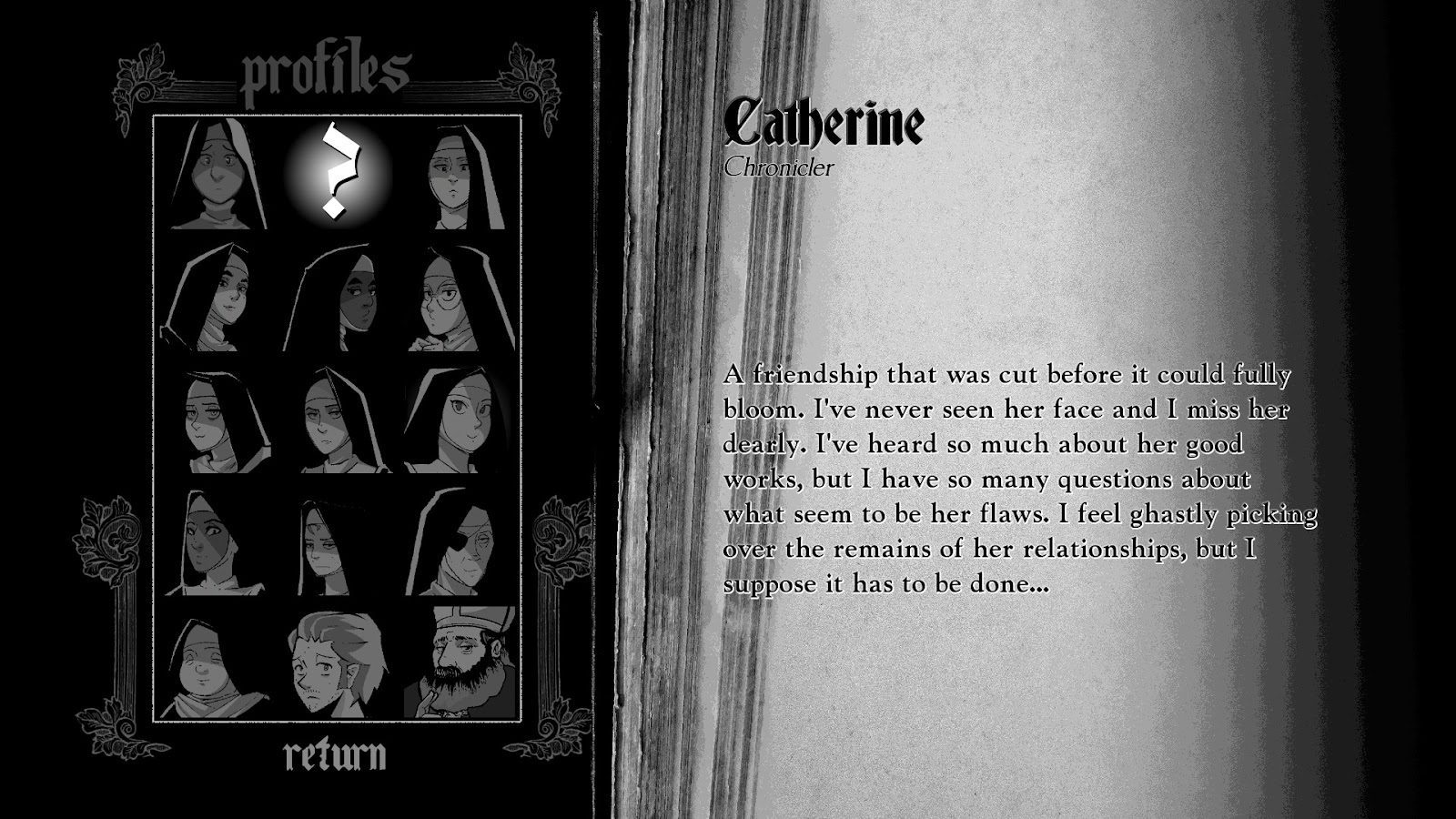

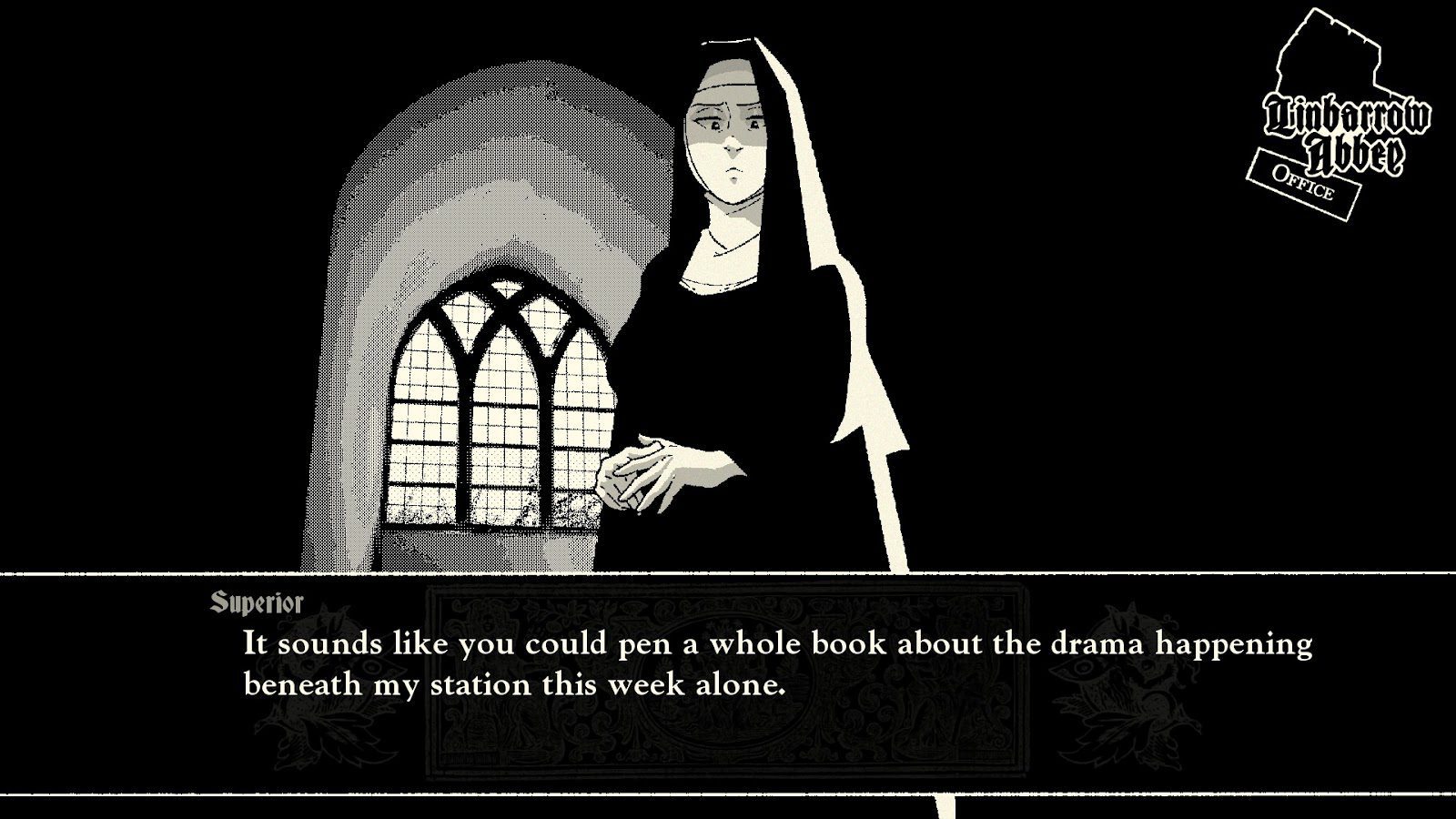

If I was being fresh, I’d describe the style of the game as “goth Gothic” – Misericorde does a lot to combine the modern sense of the word with the ancient. Pictures of beautiful church architecture are derezzed & desaturated, giving it an almost retro-gaming aesthetic. It’s contrasted by some interfaces reminiscent of Persona 5 – again, the ancient and the modern combine. Musically it’s hit or miss for me – older saltarellos are rendered in chiptune, and abstract jazz veers into discordant harmonies. That being said, not all music is meant to be pretty, and it certainly does a good job unsettling you. The characters are lovingly illustrated and contrast the distorted realism of the backdrops. Their designs do a fantastic job conveying the words they’re saying.

Which, being a visual novel, there’s a lot of. I’ll admit, visual novels are not my go-to genre of games. I see their value, but I prefer to be able to make choices, even if it’s just an illusion of choice behind the scenes. Video games are by definition interactive. Still, even if it leans more towards the “video” than the “game”, visual novels can be a better vehicle for a story than pen and paper. Music can set a mood, and pictures help cut to the chase of the narrative, eliminating unnecessary scene-setting.

And the story does a good job of gripping you as much as solid gameplay would! It’s an intriguing story and highlights much of the themes of the time: corruption in the church, theological questioning of established dogma, and more. At the same time it feels anachronistic in its word choice and characterization. However, this is by choice and not by accident.

As an artistic choice it is usually fine; however, some of these anachronisms are a detriment to the characters. Modern sensibilities and concerns clash with some concepts that would have been understood by educated people then. There are social mores that are hand-waved away by various characters that would have shocked them back in the day. I don’t want to paint a rosy picture of the past; there was plenty of sin and scandal back then too. But the indifference towards sin on display doesn’t seem characteristic of the nuns who chose to be there. Perhaps there’s more underneath the surface…

If you were a woman and wanted a good education back in the 15th century, one of your better options was to become a nun. The Church invented the university, after all! But many of the questions raised seem to come from a place of ignorance on what the Church taught back then. When the Church’s teachings are rightly remembered, some of the sisters tell Hedwig she’s being too rigorous. In certain situations they are right – Sister Hedwig is very rigorous, especially with herself. However, some of these sisters need a bit more rigor in their lives.

It does its research, but in some areas doesn’t dig deep enough. I’m reminded (again) of Pentiment and Josh Sawyer’s approach: ‘if these were intelligent, rational people, why did they believe what they believe’? Faith seems to be more often depicted at odds with reason than complementary to it. Faith and reason both point to truth.

But then again, shouldn’t I ask the same of Misericorde? If I know this game was made by a rational, intelligent person (which it was), what do I think the game is trying to say?

Honestly, a lot. What stands out the most to me is its subtle commentary on scrupulosity and self-flagellation. Hedwig, narrating from the future, often states how much she deserves all this punishment, and in the present any praise directed her way makes her sick to her stomach. Humility, however, is being honest about who you are in God’s eyes. So yes, we are sinners. But God made us so that He could love us.

Hedwig falls into the trap of scrupulosity that too many of us do – that semi-pelagian idea that love and grace has to be earned by our actions. But as soon as we fail, so does our self-worth that was tacked on to our actions. God doesn’t want us to be good because it benefits Him or supplies a lack in Him – He wants us to be good because that is what’s best for us. He loves us in our brokenness, no matter what, and as soon as we turn from our sin back to Him, He runs out and meets us halfway.

I can relate to this struggle, but I know many ex-Catholics have as well. They feel that all we’re taught is shame for our sins, and for those of us who do peddle that, I’m ashamed. So many have left the church because of this. But that is not the truth of our relationship with God. Jesus died personally for you. Not the royal you – He died for you. He leaves behind the ninety-nine sheep to find the single lost one, and rejoices having found it. Love can demand things of us that might hurt to give up, but in the long run it will be so much better. Guilt over hurting someone we love is natural, but shame is when we uncharitably disparage ourselves for having done such damage. If you find this describes you, I’ll conclude by just saying God is mercy. You don’t need to hold on to it anymore.

Misericorde is told in parts, and I’ve only finished Part 1 as of completing this review, so I am reviewing an unfinished story. Part 2: White Wool and Snow was just released in January, and I plan on reviewing it as soon as I can, so take my opinions for what they’re worth; they might change once the final volume is released. But as it stands, Misericorde is a good, sometimes great visual novel that’s befuddled me at the same time. If you’re going to play, be spiritually prepared.

Scoring: 83%

Art: 9/10

Music: 7.5/10

Story & Writing: 8.5/10

Morality/Parental Warnings

Divination: one of the nuns uses tarot cards to predict the future. Asides from the moral issue, it also turns out this is an anachronism, as tarot used for cartomancy didn’t exist until the 1700’s. The more you know!

Nudity: there are two bath scenes in the game. Everything is technically covered up, but enough is implied for it to be a potential issue for some.

Language: Adult language runs the gamut in this, Katherine being the worst offender.

Lewdness: The nuns sometimes talk bawdily.

Demonic / Pagan Imagery: [spoilers] There is a satanic-looking symbol hidden somewhere in the abbey. A ghost seemingly appears to Hedwig and chops a goats head off. A barghest chases you at the end of the game.

Representation of Faith: Misericorde gets many details right when it comes to the historicity of the fictional abbey. Their routines and responsibilities are well captured, though the amount of prayer gets off-screened shortly into it. It even has some accurate philosophy and theology; however, while there is some theological understanding, it’s not comprehension. The story of Elisha and the bears is brought up early in the game. When not read carefully, it is a complicated story! Here’s a link to a more in-depth analysis of the story, though I’ll address what I can in as short a time I can.

In brief, Elisha goes to a new country, and is accosted by some young men. They say “go away baldy”, he curses them, and then bears come out of the woods and maul the young men. Now, the translation of the time said these young men were boys; a more direct translation of the Hebrew actually equates the phrase to “foolish or unwise young men”. The latin word “pueri” usually indicates boys, but it too can also be translated as “bachelors”. Another point when we look at the translation is that the young men tell Elisha to go away; but this same word is used for when Elijah went up to Heaven. So the initial translation sounds like schoolyard ribbing, but the implication is that they want Elisha to die.

Another assumption many make when reading this passage is that Elisha calls down the bears on these young men. But when you read it again, all Elisha does is curse them: God judges the young men’s hearts and sends the bears. This might not be very convincing to an atheist, but the point is they were not punished by Elisha, especially not over hurt feelings. Elisha has no authority over God, after all.