Tabletop RPGs can often feel like more work than they are worth, and a lot of that I think has to do with the difficulty of successfully engaging in subcreation through play. Many DMs feel immense pressure to bring something highly unique to the table in order to hook their players, and as such they can spend years agonizing over discovering the right system and crafting an original setting. The dream in this hobby is to create games and stories that could only come from your perspective after all, but without being professional worldbuilders in your own right this can feel impossible at times. It was this reality of TTRPGs that was brought into perspective by today’s title, and the more I immersed myself in it the more I wanted to give it a proper reflection. Special thanks to TheGoodHoms, Starwarp, and Catholic Twitch streamer ZergTron for being players in my campaign, still ongoing as of this writing!

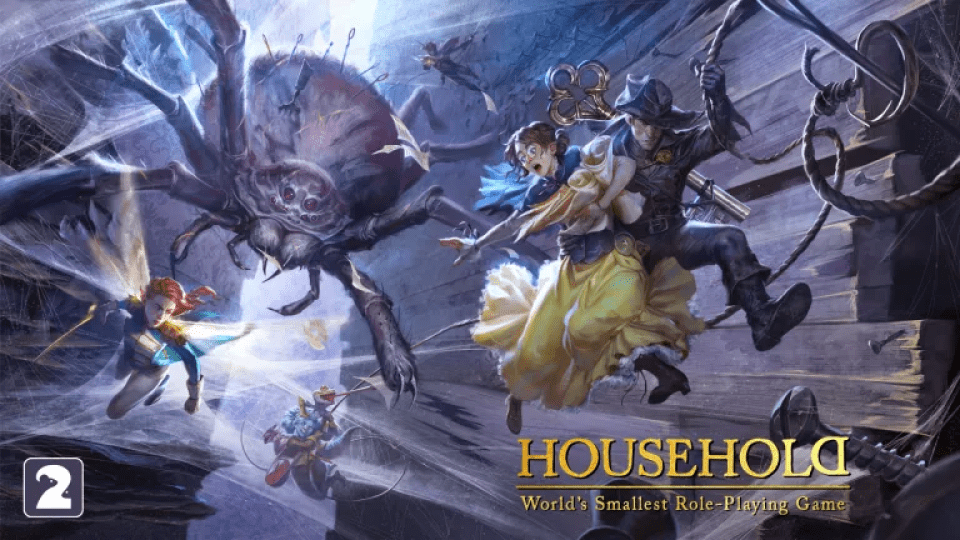

Written and developed by Riccardo Sirignano and Simone Formicola, and published by Two Little Mice, Household is narrative-driven tabletop roleplaying game released in 2022. Its premise involves a collection of tiny people creating a society in a long abandoned human house, and tells the history of how they lived their lives and how a fragile peace was pushed to the breaking point. Players interact with the game through creating characters and telling a story together, rolling dice to resolve challenges and uncertainties. Please note that I own the pdf versions of all the volume one books which will be used for this review. There is also a 5e variant of the game under the title Adventures in the Household and I did buy that version on sale as well, but this article will not cover that version of the game. Also keep in mind that Volume II is not out at the time of this writing.

The setting of Household takes place in an abandoned human house sometime in the early 1800s and follows the tales of the Littlings. These are a collection of small people based on European folklore, and includes the fairies, boggarts, sprites, and sluagh. The backstory leading into the game is dense, but I’ll try to condense it as much as possible. After the family living in the house disappeared a roughly 90 year history kicked off where those littlings who had been living in the walls even during the family’s time, as well as a couple of peoples from afar, founded nations and fought in bitter conflicts to control the destiny of the house. In recent times an uneasy peace has been forged thanks to the creation of the High Council and the signing of the Astraviya Treaty, which negotiated a rule of law to be upheld throughout the house. The game itself begins 97 years after the Master’s Disappearance and 6 years after the Council’s creation, and covers the 5 years over which the Fragile Peace is slowly unraveled.

Perhaps Household’s most unique feature compared to other ttrpgs is that the game is not framed as you creating a totally original story. The campaign is grounded in a particular point of Littling society’s history, with certain events being completely inevitable within the timeline. The focus is instead shifted onto the player characters themselves, with the primary task being to explain their part in history through playing the game. In practice this means that no matter what corners of Household the group ultimately decides to delve into, life goes on in the background and the world of the game is alive and moving without much extra effort needed to showcase that. Individual adventures are almost always self-contained narratives that take place months apart from each other so you’re allowed and encouraged to introduce some off-screen developments, and you can even change over to a secondary character or switch GMs between sessions if you want. If your goal is to play a sandbox-style game where players can radically alter the status quo of the setting this game will be a disappointment. If you like the setting of Household and are down to find your place in it though, then it is a truly satisfying experience.

I honestly can’t stress enough how captivating the world of the game is. The core rulebook details the history of the house leading into the game in lavish detail along with the major regions and cities, while the Practical Guide to Living Inside the House adds a ton of addition information such as more niche settlements, legends that make great plot hooks, and a crazy deep dive into the politics, martial traditions, cultures and more for every nation in the game. I didn’t even use most of what I read directly, but it was all so engrossing that I couldn’t help soaking in all the details so that my DMing would be as on-point as possible. It also helps that the game takes its world and characters quite seriously. Beneath the cutesy premise of playing as a bunch of little folklore people in a Borrowers style setting with magical contracts and such, there is a fairly mature Napoleonic-era drama of wildly different peoples struggling to coexist despite their differing ideals. While the game is ultimately still what you make of it (this is tabletop after all), this is one of the most well-realized settings I’ve ever engaged with, and an incredible scaffolding from which to build a campaign.

But how do you play Household? Well, players begin by designing some characters they’d like to tell the stories of. It’s a fairly simple process which is lighter on customization than most systems, but if anything helps build solid characters with variety, strengths, and weaknesses. Race selection is referred to as your ‘folk’, and this provides both a cultural context for your character as well as a Hereditary Contract. Contracts are the closest the game comes to having magic, and provide players with a powerful ability in exchange for a roleplaying requirement, with Hereditary Contracts being simple “get this power, keep this promise” affairs. Fairies can fly but have to keep any agreements they undersign with their name, Sprites have three sub-folks themed around elemental powers but have to honor any agreement they accept money for as part of the deal, etcetera. Failing to keep your promises causes the enchantment of the house to punish you with Terrible, Terrible Things, so you’ll need to make amends if you slip up. Altogether a pretty fresh mechanic that oozes flavor and provides great roleplaying opportunities, though players generally have to consciously choose to put their character into position to potentially break the contract for TTT to really be an issue, so one must be a sport to get the most out of it. There are also special Personal Contracts which characters can discover that provide crazy good benefits at some really wacky behavioral costs, so advanced players can choose to make Contracts a more involved part of the game. Back to your budding protagonists though, a refreshing aspect of this is that your folk does not determine your character’s ability to excel at any particular area of the game, meaning certain folk aren’t pigeon holed as ‘the martial option’ or ‘the face option’ and encourages a lot of creativity.

Said proficiencies are actually determined by your Profession and Vocation, a class and subclass system which determines the bulk of your abilities. Each Profession and Vocation provides a Field proficiency and ten Skill points, which determines the sizes of dice pools you roll while making checks. So a Soldier will always have Field proficiency in War as well as ten specific Skill points, but two Soldier players might have fairly different stat spreads if, for instance, is Soldier A is a Cadet with proficiency in Society while Soldier B is a First-Class with Academia proficiency and each with ten additional Skills. Granted characters in the same Profession do overall tend to play pretty similarly, but you do get four extra skill points to allot as you like (plus more as you level up) so it’s not completely rigid.

There are more things determined by Profession and Vocation, but at this juncture it might be best to explain Household’s core mechanics. Whenever a player wants to take an action to advance the story that might have negative consequences for failure, they consult the Field and Skill stats for the check they are making and roll six-sided dice equal to the number of points in each. Commonly the Skills have an associated Field, but they can be used in other Fields given the right circumstances (i.e. Elusion is typically used in its base Field of Street to represent stealthy movement, but might be used in Society to carefully change subject in a tense conversation). Success is determined by how many matching die faces the roll produces, with two-of-a-kind being a Basic Success, three Critical Success, four Extreme Success, and five Impossible Success. Once a die shows up as part of a Success it cannot be changed, but rolling even one pair allows the player to Re-roll any lone dice in hopes of gaining a new and/or improved Success at the risk of losing the one they have if they are unsuccessful. If that works out you can even go All-In to improve further at the risk of crashing out and losing all of your accumulated Successes.

This core dice mechanic, lovingly nicknamed the “Yahtzee System” by my game group, is the framework which most other mechanics in the game are built around. For instance the Professions and Vocations (and progression) provide Traits which often add +1 to rolls of a certain nature, like Pickpocket adding an extra dice to attempted theft, or grant Free Re-rolls which allows you to perform your Re-roll without risk of losing your Successes, such as Know-It-All while attempting to recall information about the house and its history. Various items, npcs, and circumstances can also add +1 or -1 to your rolls, known as being Helpful or Hindering, so there are a lot of ways to swing the odds around. Overall this system is very intuitive once you wire your brain to look for matches instead of looking at the numbers themselves, and keeps each check engaging by incorporating a press-your-luck element to every challenge.

There are many other mechanics to consider too. Another related mechanic is Moves, a set of special abilities that can be used once per session chosen from a list available to your Profession, and sometimes grant +1s and Free Re-Rolls but just as often allow you to automatically do cool things like safely fly somewhere with a bumblebee’s help or burst into a conflict scene you weren’t originally part of. These are probably the most memorable resources to use out of them all, and are a lot of fun to pick more of while leveling your character. Perhaps less impressive is the Memories system, which allows players to invoke past experiences as Helpful to certain checks, as while this is an interesting take on freeform progression it can be hard for players to remember these are even on their sheet and look out for opportunities to bring them into play. My personal favorite mechanic is Decorum, a character status which represents how well-put together or fancy their attire is, and has a direct effect on how the Littilings around you react. Increasing Decorum is expensive too, and lowering it can be the result of a failed roll or an ability’s cost, so players need to be able to know when to cash out to make an impression and when to cut costs by dressing down. Social mores don’t often have this kind of direct manifestation in TTRPG games, and it really adds to the game’s atmosphere.

While I could go on about other gameplay mechanics, I’ll cap things off by quickly going over Household’s combat systems. Conflicts see the players make a variety of checks, whatever ones they see fit in fact, in order to deal stress to their opponent and overcome fearsome foes. All checks are made in the Field of War, but otherwise you can attack directly with Fight, insult and demoralize with Eloquence, perform a sneak attack with Elusion, and much more. The opponent only takes one turn per round like a player, but attacks every player at once to compensate and dictates the necessary defensive roll depending on their approach. As fights progress opponents also unleash powerful Moves of their own in accordance to the damage they take, so even as the heroes gain the upper hand they have to be careful. My one issue with Conflicts is that opponent Traits are intended to be the main means of spicing up each encounter more passively, but the strong enemies can have a lot of conditional modifiers to keep track of and some Traits are basically mnemonics for combinations of other Traits, so they can get really difficult to actually run. Some Traits are just mean too, like the ones that limit the amount of damage an opponent can take even if your player just rolled a devastating amount of damage. Just let them have their cake dangit! The other major combat system is Duel, where the player and narrator roll dice-pools against each other in a bid to win on the offensive three times, and opponents can invoke strengths and weaknesses to change the flow of battle. These are typically more narrative heavy since regular stress isn’t used, and Duels tend to end swifter than regular Conflicts. I think they’re a fun addition. Overall, the gameplay of Household presents a good mix of social, exploratory, and martial scenarios that’s easy to learn thanks to a strong central dice engine, and is well presented as a tool to move the story forward rather than stall out encounters.

Next I’ll give a brief overview of the contents of each book of Household as something of a buyer’s guide. The core rulebook is of course mandatory and covers all the mechanics and lore you need to start playing, so there isn’t much to discuss. The Practical Guide to Living Inside the House I mentioned earlier is also as I said: a hefty volume that expands upon the lore of the setting to really make it come alive for people who live for the little details. You can weave a fairly compelling campaign with just the core rulebook so this one isn’t mandatory, but it can really broaden your perspective on the setting as a whole and present new narrative ideas if you find yourself invested in the lore. A favorite NPC of mine who I eventually got to play a session as a PC with is actually based on some lore within this alternate book. There’s also a smattering of extra Vocation options for players that want to be a little unique, but they’re nothing too crazy.

The other optional book is A Saga of the Fragile Peace, a campaign book which provides 24 premade characters, 6 pre-written adventures for Chapter I, and 61 adventure prompts for the remaining Chapters. This book primarily exists for players who prefer further structure beyond what the base game provides, and can serve as something of a ‘canon’ version of Household’s timeline if you prefer. You can even pick one of the 24 characters as a de facto protagonist and play 11-12 sessions following their full story! This one is the most specific in terms of target audience so probably not mandatory for most players, but I do love its approach to adventure modules and wouldn’t mind playing through the campaign with it one day (maybe following Dimitri Sokov since I’m quite fond of The Realm).

No matter what books you buy though, the presentation is sure to impress. The writing is not only clear and informative, it is written as though it were a diegetic artifact uncovered from the house itself and the prose is from the perspective of a boggart named Herasmo Hemingway. This is always a favorite technique of mine in ttrpg books as it allows the writers to develop the world’s setting in a way that feels lived in. It also adds just enough unreliability to the narration of events that players are free to make their own judgements about which characters and factions are right and wrong, and in turn make the setting truly their own without having to reinvent the wheel. The artwork in the books ranges from gorgeous pseudo-realistic paintings, to striking concept art, to charming political cartoons, and all of it is a pleasure to look at. Rulebooks as wordy art books is a trend that has taken a bit of a toll as time has gone on, but Household benefits immensely from all these drawings as they effortlessly transport the imagination to the fiction’s world and gets you excited to schedule your next session. My only real criticism with the books’ presentation is in the core rules, where I think the game might have benefited from moving chapter four to earlier in the book (maybe to chapter two) so that players would be encouraged to get familiar with the game’s dice mechanics before being asked to create a character.

Talking about the spiritual merits of a ttrpg is always a challenge because often the moral of the story is up to the players more than anything, but I do think Household has at least one aspect of its lore’s design I think is worth examining from a Catholic perspective, even if a bit of a meta one. Spirituality itself is a surprisingly subtle feature of the setting’s design as the game lacks any sort of traditional arcane or divine magic, opting instead for the more enchanting set of soft magic forces and the Contracts. This does cause religion in particular to be sidelined as a background detail slowly fading from societal consciousness, and there is something deeply melancholic in how it reflects our own world’s historic decline into a secular shell of itself, but in a way I think the game benefits from this approach. For one it lends all encounters with the supernatural you do come across as genuinely ineffable and sublime, and powerfully resistant to any attempt to gain mastery over it. In this way I see a reflection of how the material and spiritual realities of our own world intersect: always just below the surface yet dramatic in its effects and impossible to deceive into your advantage. It’s a feeling no other system has really been able to capture, and I’m not sure where else you can get this kind of experience.

For the vast majority of tabletop RPG systems there is and probably always will be an undeniable hurdle for religiously serious players in just how off-putting so many of their depictions of faith and the spiritual can be. These games often feature a hodgepodge of warring gods whose ambitions warp the entire setting and themes of the game around themselves in really loud and obvious ways, assuming the games don’t find a way to undermine or villainize the divine outright. While such a thing might fit these games on its own, it’s hard not to feel a little bit cheated when you sit down to play a pious character in earnest only to find the games give off a flippant air that ridicules that honest desire (as written anyways, house rules are the lifeblood of this hobby). With Household cutting away all of the pulpy nonsense it invites the player to encounter the spiritual with the solemn gravitas it deserves, and ultimately engage with the ethics of Elfland which lead back to God. In that way Household shows us that sometimes the best way to find reflection on the spiritual is to not mindlessly pick a game that says you can be a cleric, but to simply play something with tasteful focus on its own ideas and allow reflections on spiritually to emerge naturally from the pieces you’re given. It’s a worthwhile thing to consider when deciding on your next campaign.

In conclusion, the best way of expressing my opinion on Household comes down to the way I felt when I first finished reading it. The majority of RPG books I read tend to give me plenty to imagine as far as scenarios I could see myself being a part of, but it’s hard not to ultimately view said musings from the perspective of a player character. Everyone has a natural drive to be a protagonist like that, and while one can certainly submit themselves to the role of game master for the sake of the group it’s hard not to feel something was left behind in order to make the game actually happen. Not to mention when I do sit down to run them, I always end up feeling the need to adjust major elements of the game’s setting and rules (if not make my own world outright) just to hit the tone I’m actually looking for. When I read Household however, it was the first time where my desire to play as a player was only matched by my excitement at the thought of being able to run the game for my friends. And most critically, I wasn’t compelled to change much about the setting. Perhaps to put it more simply, it is the first TTRPG I am able to find myself in unconditional love with. It absolutely has its quirks and rough edges in addition to some design choices that are borderline heresy to traditional RPG sensibilities, but if you give it an inch it will take you the whole nine tiny-meters. Household is an incredible game filled with novel mechanics that make learning the game easy, and defined by one of the most well-realized game settings I’ve had the pleasure of exploring. The structure is ideal for easing newcomers to this type of game into the ins and outs of both playing and game mastering, yet interesting enough to offer grizzled veterans a breath of fresh air. If anything about this game has struck you as neat, it is definitely worth the asking price. The stories of the Littlings are certainly going to stick with me for many years to come, but especially the ones my players and I created together.

Scoring: 95%

Gameplay: 4/5

Story: 5/5*

Art: 5/5

Writing: 5/5

Replayability: 5/5

*Story in this context refers to the quality of the setting, its canon history, and the way it seamlessly moves in the background of the campaign. CGR does not guarantee that playing the game will make your table into a cadre of master storytellers.

Morality/Parental Warnings

Household is a tabletop role-playing game starring tiny peoples from European folklore. There is no explicit magic in the setting, but a variety of metaphysical enchantments called Contracts underpin the more fantastical side of the setting. They are framed as agreements that provide certain supernatural concessions to the littling, at the price of a counterpart they must follow or suffer increasingly worse consequences if they don’t make amends. Hereditary Contracts simply exist as spiritual realities of the various folks and Welcoming Contracts are just magically enforced entry waivers, but certain Personal Contracts can feel like deal-with-the-devil type affairs (demons are not actually in the setting, but there is a giant spider named Mammon who offers the Goldthirst Contract). The only two instances of religion in the books are the Spider Idols worshiped in The Great Horde, and The Church of Safekeeping in the Hearth Republic. The former is regarded as a set of unnerving but popular superstitions, while the latter is regarded as a positive but waning force in society. Monsters in the game are literally just a bestiary of common house pests. The characters wield a variety of weapons themed around household items like pins, needles, keys (including varieties that are firearms), cutlery, etc. One of the Professions is entirely dedicated to playing as a Criminal, with Vocations for it being Courtesan, Cheater, Thief, Professional, Snitch, Thug, and the bonus Bandit in the sourcebook.

The main themes of the game’s built in lore and setting generally resemble the cultural and racial tensions of our own times, as well as debates between international cooperation vs national sovereignty. The most obvious figures in this respect are The Tristarred, an ultranationalist terrorist group from The Realm which the game draws not-so-subtle parallels to ‘German socialists’, especially in the artwork featured in the Practical Guide sourcebook. There’s also an adventure hook about a stage play that depicts a politically charged theater production coming under fire from the public, especially because its boggart protagonist is portrayed by a sluagh. This seems particularly tone deaf because the game depicts protecting the play as an act of heroism in the name of artistic freedom and racial tolerance, while forgetting that boggarts have the smallest population and have suffered immense hardship while the sluagh are the largest and are one of the more powerful groups (put simply it celebrates giving a role for a minority to a member of the majority, boy they did not think this through). Marriage in the world of Household is described as distinct from the sacramental inviolability we know of it, however I am inclined to give it a pass since Hereditary Contracts would imply the ability to entrap someone in a magically enforced abusive marital relationship. Artwork in the game is mostly tame, with only a few slightly spicily dressed men and women.

Keep in mind that as a tabletop roleplaying game, Household allows you to basically alter or remove mechanics or lore elements as you see fit and nobody is able to stop you.