Twenty-five years ago, with waves crashing against an open coastline and a choir intoning a haunting melody, Final Fantasy VIII made its memorable debut. The game that followed was a swift adventure with relatable protagonists, a memorable love story, unique character customization systems, and what is perhaps the series’ most famous side-activity. Even with all of that (and more) to commend it, FFVIII seems to live in the shadow of its PS1-era brethren. It still has plenty of fans, and in fairness to a series where each entry is so unique, ranking Final Fantasy titles can be a difficult and silly exercise.

Except in the case of Final Fantasy VIII, which is objectively the best. (Editors’ note: Whatever…)

Maybe that’s an uncharacteristically sweeping assertion, but de gustibus non est disputandum. If it hasn’t been clear from my review history, there are few Final Fantasy games that I don’t thoroughly enjoy, but Final Fantasy VIII has always had top-billing.

FFVIII’s story and mechanics cohere in meaningful ways, and it’s capped off with one of the series’ most satisfying endings. From the beginning, you’re given interesting mechanical decisions, and engaging with the game’s systems removes or recasts what would otherwise be typical JRPG tedium. Finally, and most importantly, Final Fantasy VIII tells a tale about growing in faith and humility, heroic self-sacrifice, and a fight against a villain who wants to be a counterfeit god. What more could you want?

Final Fantasy VIII’s story centers on Squall, a pensive and competent up-and-coming student at Balamb Garden, a school for mercenaries called SeeDs. Squall and his classmates are approaching their induction as SeeDs, and are given a mission to defend a peaceful town from an attack by the nation of Galbadia, which has recently developed imperial ambitions. The disobedience of Squall’s rival, Seifer, causes the mission to go awry, and Galbadia is able to take over the town, and more importantly, its rare communication tower.

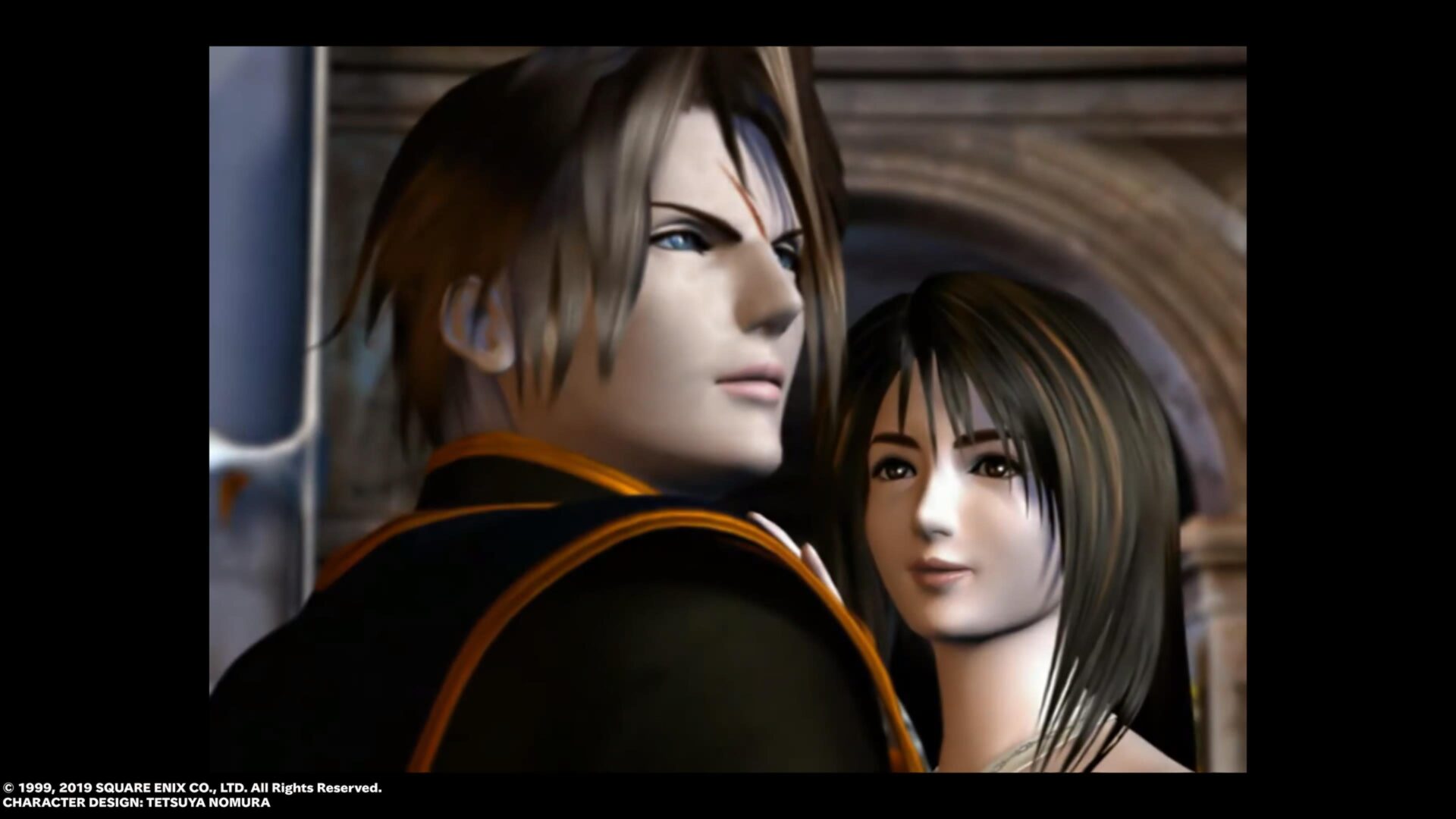

Seifer is reprimanded for his actions, but Squall and his squadmates are permitted to advance. Now fully-fledged SeeDs, they’re immediately dispatched to the Galbadian-occupied town of Timber to aid with a resistance movement. In accordance with JRPG tradition, as you complete these initial pedestrian objectives you’ll uncover a larger plot with world-spanning consequences. However even at its wackiest, FFVIII manages to stay grounded through its focus on Squall and his friend (and eventual love interest), Rinoa. While superficially the final villain’s aims may seem to be standard-issue lightly-explained mustache-twirling, closer inspection reveals that they externalize important conflicts within both our hero and heroine.

Further discussion can only be held in spoiler territory – skip ahead to the Spiritual Value section if you’re already on board.

The fundamentals of playing through Final Fantasy VIII’s story follow series conventions (at least among the first 10 entries). You’ll take your party of heroes through a fantasy world, advancing the plot primarily through success in turn-based battles. However, FFVIII departs from the norm through the controversial design decision to allow enemies to level up along with the player characters. Since experience-based character-growth cannot be relied upon to gain an edge in combat, FFVIII provides the powerful, deep, and perhaps initially complicated “Junction” system.

“Junctioning” refers to two actions in Final Fantasy VIII: assigning a Guardian Force (GF) to a character, and assigning magic spells to character statistics. Junctioning a GF to a party member allows him or her to call upon it in accordance with the series staple of summoning magic, and also grants access to a skill tree unique to said GF. These skill trees combine active, passive, and junction abilities, the last of which give you the option to invest spells into specific character statistics. For example, dedicating Cure to HP would boost that character’s health points – and would do so more effectively than Fire. Fire spells might be better invested in Strength, but then again you could also put them towards an elemental attack, sacrificing a small global boost to your attack power for a significant advantage against enemies weak to fire. You can also…(Editors’ note: we’re cutting Spicy off here in the interest of preserving your sanity and time.)

Junctioning magic depends on another design departure: each spell is stored in a discrete unit. There’s no MP, and your spells do not reset to some maximum when you rest. They function more like cards in a deck, which seems to be the intended analogy, given FFVIII’s Triple Triad card game and the Draw command for obtaining spells. Drawing can be performed both in combat, and at particular points strewn about the world, but there’s numerous ways of crafting spells outside of combat as well.

Since the Junction system provides non-combat means of building and customizing your characters, battles become something you want to do for specific reasons, rather than something you must do to crest an arbitrary milestone. In FFVIII, you do not need to wander aimlessly until numbers get bigger. Instead, you might want to buy certain items for crafting purposes, or fight certain enemies because you want to draw a certain spell, etc. (Editors’ note: so you’re wandering purposefully for numbers to go up.) (Spicy’s counter-note: yeah, but it’s fun.) Then, when you’re happy, you can turn off random encounters entirely once you find the GF that has that ability.

If you’re playing this game today, congratulations on your fantastic taste. Also, you’re probably playing the remastered version which has nicely redone character models, but has pre-rendered backgrounds which show their age, at least from a technical standpoint. They’re still successful on the artistic and cinematic fronts, with camera angles that feel like deliberate choices to match the drama or subtly hint at things to come.

FFVIII is a delight musically, too, as Uematsu knocks another one out of the park. It feels to me like a breath of fresh air after the often gloomy tone of FFVII’s soundtrack. There’s the Dorian flavor of the main theme, “Blue Fields”, upbeat battle themes “Don’t Be Afraid”, “Force Your Way”, and “Man with the Machine Gun”, the meditative “Find Your Way”, supremely chill “Fisherman’s Horizon” and “Breezy”,…(Editors’ note: you can’t just list the whole soundtrack.)

I could go on, but there are some aspects to criticize, too. It’s fair to say some of the plot reveals may stretch beyond where some players are willing to suspend their disbelief, and there’s magical jargon undergirding the villain’s plans which are outlined with little more than handwaves. However, I find that all outweighed by FFVIII’s lighthearted tone and mechanical flexibility. In a way, I’m reminded of Final Fantasy V, another excellent entry which allows itself to be a little goofy, and provides a bevy of customization options to players. However, what really struck me with this latest replay was Final Fantasy VIII’s surprisingly meaningful core.

Spiritual Value

Final Fantasy VIII has all the heart and humor you’d expect from a story about a group of friends banding together to save the world. Instead of spreading characterization across a large party, though, Final Fantasy VIII chooses to focus on Squall and Rinoa. This does come at a certain cost, since the rest of the heroes are somewhat static. What it buys is the opportunity to demonstrate the main two protagonists’ meaningful internal conflicts, and then mirror those in a well-crafted foil.

With Squall, we see a young man who actively avoids building relationships of any kind, and who generally acts uncaring and guarded. FFVIII’s internal-monologue bubbles and flashbacks, however, tell the rest of the story. Orphaned by war, Squall’s only familial connection is his half-sister Ellone. For a time, they’re able to live in the same orphanage, but Ellone’s eventual disappearance devastates Squall. That loss scars him, and he adopts his loner demeanor both as a means to avoid further pain and to avoid being a source of others’ disappointment.

Squall’s attempt to control his present environment and close himself off to others as a way to prevent pain is self-defeating. Rather than freeing him from his past, it effectively traps him there. In this, I see the relatable tendency to want to control every variable to try to stave off uncertainty. Uncertainty is difficult to accept, because it’s a reminder of our contingency and mortality, but to believe it can be eliminated entirely is to idolize an illusion of control. At the very least such a belief is a rejection of the Cross. Our ultimate goal is not comfort, but Christ, and as He says, “If any man would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. For whoever would save his life will lose it, and whoever loses his life for my sake will find it.” (Mt 16:24-25).

God doesn’t expect us to bear our crosses on our own, though; rather He gives us the grace we need to carry them. However, it is a gift we must accept, and that requires an act of faith, recognizing that no matter what, God loved us first. Squall, then, illustrates the challenge of opening one’s self to love in order to take up his cross. Given his tragic past, it’s natural Squall would find the vulnerability that faith and love require to be difficult. He has to recognize that his own efforts are not sufficient, and therefore that there is a power beyond his own. However, the answer was not to close in on himself. Squall grew into his role as a leader (and his capacity to love and serve) to the extent he allowed himself to be loved by his friends. So it is with us – we grow into what God wants us to be through a humble response to His love for us.

While Squall is troubled by his past, Rinoa struggles with her present and future. At first, she is stymied by her powerlessness. She wants to free her town from the Galbadians, but doesn’t have military skills like the SeeDs. Even after she’s welcomed into Squall’s team, she never quite feels like she measures up.

Rinoa then finds out she’s next in line to inherit power sufficient to rule the world.

Unlike her predecessors, though, Rinoa is willing to trade her future, and all of that power, for the sake of her friends. In that, she demonstrates a heroic and Christlike humility. She could have had a sort of equality with God, but did not consider it something to be grasped. After she learns of her power, and understands the consequences of giving herself up for the sake of her friends, she shares a touching moment with Squall remarking how she wishes the present could stand still, and it’s here that we begin to see the artistry in FFVIII’s villain.

Ultimecia, who we learn is the source of the problems that beset the world of FFVIII, is a sorceress from the future, with power like Rinoa’s. Her goal: to compress all of time and space into a dimension she controls. Rinoa might want time to stand still, but Ultimecia makes it happen. Why? We’re never really told – however we can look at Squall and Rinoa, and make some educated guesses. Perhaps she has scars of her own in her past, and is unwilling to face an uncertain future. Or, perhaps recognizing the power she has, is unwilling to accept a future where she might lose it. Either way, Ultimecia wants to hide from the truth, that there is a power beyond her own. Our heroes, though, learn to face that fact without fear. They take up their crosses and sacrifice for their friends, and in so doing, save the world.

I already want to play it again.

Scoring: 96%

Gameplay: 5/5

Story: 5/5

Art and Graphics: 4.5/5

Music: 4.5/5

Replayability: 5/5

Parental Warnings

Suggestive Themes: The sorceress villains wear revealing outfits, with Ultimecia’s being a more extreme case, but she is not often seen. The Guardian Forces Shiva and Siren are both scantily clad. There is a scene where a man is invited to a woman’s hotel room, but the what-you’d-expect subtext which doesn’t ultimately happen in effect highlights the man’s innocence and wholesomeness.

Violence: Relatively cartoony fantasy violence. You fight humans as often as you fight fantastical monsters, but combat is essentially bloodless.

Other: One of the GF’s is named Diablos and has a dark magic aesthetic, which may bother some.