The world of tabletop roleplaying games has always occupied a special place in the hearts of gamers as a genre that can support any kind of play experience the group can imagine. The theoretical limitlessness of a game governed only by a few essential rules and the players’ creativity has always been its core strength, and the many rule systems crafted over the years have only served to further cater to any and every possible demographic that could seek to give the math rocks a try. For JRPG fans this particular market seems primed for exploitation by Square Enix’s upcoming tabletop adaptation of Final Fantasy XIV, however I wanted to see if there were any currently existing takes available in the here and now. Lo and behold I did manage to find just such a rulebook, and after rounding up TheGoodHoms, SpicyFoodHiccups, and PB&Justice for a few sessions, I’ve got things to say.

Written by Emanuelle Galletto, published by Need Games, and first released in 2022, Fabula Ultima TTJRPG is a tabletop roleplaying game themed around enabling the creation of homemade adventures akin to those found in Japanese video game RPGs (like the many I have reviewed in the past). Players engage with the game largely through interaction with each other, but also resolve various challenges through dice rolls and the utilization of various skills and resources. Please note that I bought the DrivethruRPG pdf version 1.0 for this review, and future physical and digital versions of the game may feature updated rules.

The book is broken up into five chapters, and I shall review the book’s contents by going through these chapters in order. Chapter 1 is the introduction to the game, and covers many of the basics of tabletop roleplaying by outlining what you’ll need to play, what responsibilities will exist for the players and game master, and a few descriptive examples of what playing the game should look like. Interestingly it is in this very introduction where the most polarizing element of the entire book lies: the Eight Pillars. These eight paragraphs prescribe a set of assumptions about the worlds which Fabula Ultima supports, and while they are on the whole very helpful they aren’t without some baggage. Pillars such as Magic and Technology to inform the nature of various abilities and items, or Heroes of Many Shapes and Sizes to represent the frankly absurd levels of character building freedom you have, all work well enough. However there are some oddly specific Pillars, like Ancient Ruins and Harsh Lands, which assume a world where civilizations collapse with ease and are separated by vast distances or Everything Has a Soul imposing an eschatology of life which is exclusively animist. The group was especially puzzled by that last one. I did manage to (somehow!) wind up in a conversation on Discord where the book’s author disclosed some of the intentions behind Everything Has a Soul, such as being a convenient plot device for all things supernatural, creating pause at the idea of killing living beings thoughtlessly, and ensuring that gods in the truest sense can’t exist (because in most JRPGs the protagonists are generally capable of defeating anyone they set their minds to beating, which in the case of a literal god is nonsensical).

The conversation did give me much more appreciation for that Pillar and the others in their intentions, and if Mr. Galletto ever reads this I hope they know I appreciate how civil they were about the whole discourse even if the sudden realization of how theologically alone I was in the official server made me too afraid of getting put on the spot to stick around. I admit being confrontational is not a specialty of mine… I am PeaceRibbon after all. I do nonetheless feel compelled to very gently criticize the Pillars for limiting the game’s expression of the JRPG genre down to a smaller breadth of options then it could have encouraged. After all, it is entirely possible that a group might wish to play a more civilized and localized campaign that defies Ancient Ruins and Harsh Lands, which would only require moderate changes to the Travel system to stay relevant (think Trails from Zero or other urban-esque RPGs). Or a group might want to be open to exploring themes of theistic heroes without forcing a dissonant subconscious understanding that the characters are secretly wrong in their faith by default. (Mechanically the Souls Pillar is largely just to explain the source of magic; you can simply put forth an alternative explanation). This isn’t an especially benign issue either given this rubs up against the lack of a predefined setting, which we’ll get into later. I’m not saying the system should have supported everything, but there was certainly room for more leeway. I am sure all this talk might prompt someone to tell me to go play a 100% setting neutral system that makes no assumptions like this, and maybe they’re right, but I spent around $40 on the core rules and the High Fantasy Atlas. (The latter of which by the way is an ok book, but overall not full of info that genre veterans wouldn’t know and I don’t especially recommend it unless you really really want it.) If getting my money’s worth means a little creative liberty to make the group feel more comfortable, then dangit my protagonists are in fact blessed by the one true god of the Eternian Church, and I’ll vow not to judge other peoples’ settings if I can enjoy ours in peace! In summary the Eight Pillars are genuinely fine and if you’re unfamiliar with JRPG tropes you should probably follow them. It’s just that I am familiar with the tropes and wanted to rebelliously buck some genre traditions.

The second chapter of Fabula Ultima covers the core rules which players and game masters alike will want to read in order to play, and really this is where the heart of the review starts. This is obviously the densest section of the book by far, so I’ll try to highlight the main skeleton of the game and a few of its most flavorful touches. The dice you roll in order to determine the outcome of an action with a reasonable amount of uncertainty, or rather the core checks mechanic, is built around rolling dice determined by your stats (called Abilities in-game). Aside from a few recommended checks, it is actually up to the players and game master what kinds of stats will be tested in any given check. The strength of stats are represented by the size of the die associated with them, from a d6 to a d12, and each check tests either the same stat twice or two stats to determine which dice a player will use. Aside from making the game supremely flexible in terms of the actions you are allowed to take, it is actually encouraged for players to describe their characters in ways that fit the dice you want to roll within reason. For example if a character wants to proceed forward across a surface with water running along it like a shallow river, the game master might request a Might and Willpower roll to represent the physical and mental resolve needed to press onwards, but a player might convince the game master to allow them to roll their better Dexterity and Insight stats by claiming their character will overcome the obstacle by looking for good footholds beneath the surface of the water and quickly moving between them. This single mechanic makes no stat worthless if you stretch your imagination, and does wonders for build variety.

TheGoodHoms thinks the greatest strength of stats-as-dice is the lack of confusion commonly associated with ability modifiers in other TTRPGs. Much simpler, and better for newcomers.

From here these check systems are spun-off into a variety of different special contexts. An example would be Clocks, which represent scenarios that take multiple and/or various checks to fill up and accomplish. But the most significant mechanic related to checks is the Fabula Point system. This is a resource which every player gains access to at the start of the campaign, and is replenished at the game master’s discretion. Fabula Points represent your characters’ force of RUBBISH JRPG PLOT ARMOR, and while rolling your checks you may spend one point to reroll a failed check – to do so, you must draw upon your Theme, Identity, or Origin. Alternatively you can add the strength of a relevant Bond to the result without rerolling. The Theme, Identity, and Origin are concepts I’ll get into in the character creation section, and Bonds are relationships you nurture over the course of the game and track on your character sheet. You can also spend a Fabula Point at any time (with the game master’s approval) to introduce a new element into the story… like straight up. Needless to say this system is extremely powerful, and unlike other tabletop RPGs where killing monsters is your source of EXP, Fabula Ultima largely hastens your growth by having the players spend these points constantly. In practice with my group they’ve actually ended up hoarding these for a rainy day, probably due in part to my use of the optional accelerated leveling rules on top of our sessions being two hours on average, but I think once a given group embraces this mechanic it will lead to chaotic twists and memorable setpieces alike.

PB&Justice mentions that he felt a need to get more comfortable with the world through interacting with it before considering the use of Fabula Points. He also feels that enduring the struggle against the world is generally more fun than wishing it away.

SpicyFoodHiccups expands on this by suggesting that Fabula Points likely shine brighter in the hands of experienced players who can improvise more confidently, emphasizing focus on growing into the role of his character as a beginner. It doesn’t help that he’s enjoyed the ride and hasn’t felt the need to change anything!

TheGoodHoms summarized the previous points by pointing out the story-changing power of Fabula Points can feel too open, at least when considering that restraints often breed more focused and engaging outcomes. He does also consider storytelling a secondary feature of TTRPGs more generally though, so take from him what you will.

The last mechanic I should touch on before proceeding is undoubtedly combat, otherwise known as Conflicts within the game itself. Unlike most similar games where a grid map and various game pieces are necessary to track movement and ranges, Fabula Ultima embraces the classic video game design of characters lining up in a row and taking turns beating each other up. Round initiative is a back and forth between both sides, with characters free to move earlier or later in the the turn as they choose, and attack ranges are abstracted to the point where the real benefit of a ranged weapon is simply getting to hit flying targets. In exchange for this simplicity, other elements of a conflict are emphasized to keep the tension high. Status effects are inflicted by allies and enemies alike to lower the sizes of stat dice (thus making their rolls weaker), and elemental weaknesses are a hugely important mechanic that shreds otherwise large HP pools, basically necessitating the use of the Study action if you don’t want to waste resources on suboptimal attacks. Encounter design can be challenging to get right in terms of balancing challenge and power fantasy, but the group on the whole seems to greatly appreciate the fast pace of taking turns which is never slowed down by overly involved mechanics. Like with any TTRPG, combat does often take much longer to resolve then you anticipate, but here it feels much less prolonged overall depending on how well the party assesses the situation.

SpicyFoodHiccups praises the combat’s balance of streamlining and mechanical depth.

PB&Justice specifies that the best part of combat is the lack of any feeling that he was waiting to make his move. Actions he could take were varied and resolved quite quickly, keeping the entertainment of the affair more constant. The attack order being freeform in any given round also contributes to the positives even if he sometimes feels an overwhelming sense of open-endedness, though he admits this could be D&D 5e intuition doing the talking.

TheGoodHoms thinks that combat could have been improved by a line system akin to those in Etrian Odyssey and Final Fantasy IV, since as things stand ranged weapons are too similar to melee ones in play.

The third chapter of the book is character creation focused, although before creating characters in session zero you start by making… the world and group? Indeed, perhaps the most alien departure from standard tabletop RPG procedure in Fabula Ultima is the creation of the game’s setting itself. There’s a lot of logic in this too, as while the game probably supports play within preexisting settings just fine, ultimately if you’re going to give the players narrative power on the scale of Fabula Points you might as well make the world itself a group effort. The amount of different aspects each player is encouraged to contribute to is surprisingly daunting, to the point where my own group was taken aback by how much of the worldbuilding responsibility was placed upon them, so I do wonder if the outlined process could be more approachable. This is also where the Eight Pillars conundrum rears its head the most, where the hard prescriptions clash somewhat with an otherwise boundless world creation framework, but I’ve already spoken on that at length and it’s more of a personal gripe besides. The group creation aspect is a smart move which ensures that a group prone to the creation of distinctly different heroes can be reigned in by proposing a party premise everyone will work to contribute to. It’s definitely the lightest section of session zero, and there is a noticeable amount of overlap within the five recommended group types (Heroes of the Resistance and Revolutionaries in particular read almost exactly the same, just with the latter being a bit darker), but it can be a good tool for directing the meat of this chapter.

PB&Justice’s undying respect for the seat of game master as final arbiter of the narrative made him somewhat uncomfortable in trying to suggest new world elements of a grand scale. He proposes an alternate worldbuilding method where the game master establishes some baseline concepts and guides, from which the players flesh out the details, which may have made this much less daunting.

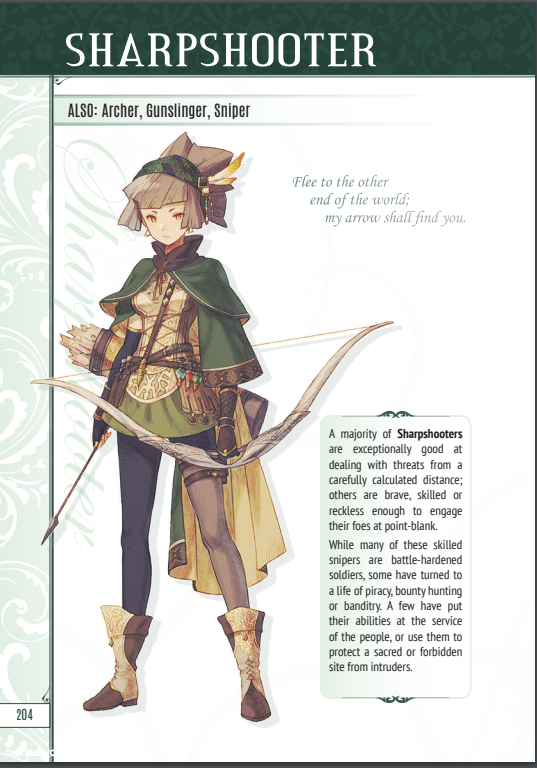

Character creation in Fabula Ultima begins in earnest with the selection of an Identity, Theme, and Origin, which represents a character’s self-perception, a central idea or emotion, and homeland respectively. These define the core characteristics which you will invoke to spend Fabula Points, so game masters can expect to tailor their scenarios around situations that matter personally to these descriptions. That isn’t to say this system is limiting though, as aside from players having radical freedom in picking what these are, they are allowed and encouraged to switch Identity and/or Theme upon leveling up to represent changes in how the character sees themself and what motivates them. The other major choice is selecting character classes, which determine the bulk of your special powers during combat and occasionally outside of combat. The twist is that every character in Fabula Ultima is multiclassed, with a minimum of two taken at the starting level of 5 and a minimum of five classes chosen by level 50 if the game goes on that long. This seems like a lot, but the individual skills you gain when putting levels into a class (or taking a new one for the first time) are usually very small, and the pace of leveling often allows you to gradually evolve your tactics without overwhelming yourself. Every level is meaningful because individual class levels cap at 10, so you’ll need to make tough decisions on what parts of a class you will emphasize as you level up. Whether you take the Rogue class to emphasize opportunistic attacks or evasion is up to you, but don’t think you’ll be a perfect master of all it has to offer by the time you’ve put all ten allowed levels into it.

PB&Justice greatly appreciated the ability to change Identity and Theme upon leveling up. “Furritive Spellblade” turned out to be a difficult Identity to play, discovering he doesn’t especially like playing quiet characters.

Both of these systems put together makes the creation of any character you want super easy, and exciting. The process of playing a dragon-taming knight is as easy as making that your Identity and choosing the Guardian and Wayfarer classes, as is making a classic Final Fantasy red mage by mixing Elementalist, Spiritist, and Weaponmaster. The lack of a built in race system and heavily abstracted rules also means you can get really wild with the stuff you come up with. Want to play a warrior from a winged race? You might not get mechanical advantages from doing so, but it’s as simple as including it in your Identity. How about a double amputee who fights by controlling his weapon with telekinetics? Be reasonable about the implementation and you can go for it. Do you want to play the fantasy equivalent of a shut-in otaku who has never exercised a day in his life but is a beast with a katana because he read a bajillion combat manuals?! Allow me to introduce you to the Weaponmaster plus Loremaster (Knowledge is Power) build. Truly the most freeform character system I’ve ever played with.

This won’t stop TheGoodHoms from playing the most archetypal knight or dwarf you’ve ever met, however!

The fourth chapter is the game master section, and guides said GM through some of the various questions you can ask to enhance the scenarios you’ll prepare, such as presenting ideas and conflicts relevant to certain player classes and how to prepare material rewards appropriate to the current level of play. The most unique game master facing mechanic is that of Villains, special antagonist NPCs which drive the story forwards alongside the protagonists and represent the greatest obstacles in the story. They even have their own RUBBISH JRPG PLOT ARMOR pool called Ultima Points, and yes spending these does help players level up… if they can survive being beaten down by rerolled attacks that is! The creation of Villains and other NPCs takes a little bit of work to understand, but once you’ve grasped how to move between different steps efficiently, it becomes quite easy to whip up a unique enemy with strengths and weaknesses tailored for your party’s needs. Fabula Ultima is incredibly good about giving the game master intuitive tools in creating adventures for those who need it, even if my personal GMing style comes more from looking at chapter two’s core mechanics and making situations/monsters based on feel.

The final chapter of the book is a small bestiary which teaches the game master how to read enemy stat blocks before handing out a bunch of sample foes from all of the game’s major categories. These are a nice bonus and I thoroughly endorse using them, but between my insatiable need to make customized foes and the fact that the sample enemies cap out at level 20 combine to make this arguably one of my least used sections of the book. An amazing reference for sure, but any GM with a modicum of experience will quickly pass over it in favor of the aforementioned NPC designer. Maybe I’d like it more if it had a wider spread of monsters for higher levels of play, but the book is over 350 pages as is so I can sympathize with trying to cut production costs.

On a brief note about the book’s structure itself, I think it’s quite flawless. Information is bolded, highlighted, color coded, and/or placed into distinct boxes to help separate out different kinds of information, and it’s hard to get lost in the book with a chapter tag adorning every other page. The artwork is also quite nice, featuring a mixture of box art worthy illustrations, chibi doodles for mildly amusing visual gags, and even pixel art for the items in the equipment tables. Definitely full marks for presentation.

PB&Justice notes that the book order – which this article reflects in its own structure – did end up as a major criticism on his end. Compared to 5e’s clever means of introducing the player to the game’s rules by having them create a character then read the axioms of play using said character as a reference point, Fabula Ultima felt like floating among a bunch of disembodied rules by comparison, only making full sense in hindsight. He stresses that 5e’s isn’t the only solution, but it did make TTRPGs relatively mainstream for a reason.

So all things considered, is Fabula Ultima TTJRPG a tabletop roleplaying experience worth running? Naturally your enjoyment of the product will probably rely on at least one member of your group (game master, preferably) having a knowledge of its inspirations with which they can insert authentic homages to, or twist the genre in ways that safe mainstream offerings never will. From a purely game design sense though, it is a great system for play groups with a very tightly knit bond. The way world creation and Fabula Points shifts the burden of unfolding the emergent narrative from the GM’s shoulders to the group more equally is tricky for a lot of people who are used to less involved styles of play, and I can imagine how messy this aspect could be if you tried playing with a group of strangers. Heck, I would consider us a step beyond strangers as pseudo-coworkers, and we still struggled with this a bit. If you are in a good group though, the game has a design laser focused on making its rules as unobtrusive to the act of roleplaying as possible, making it perfect for those looking for a more social experience from TTRPG night.

As is usual with this style of game there isn’t really anything inherently Catholic to take away from the experience, because the burden of thematics ultimately relies on what the table pursues through the narrative (unless you’re playing the likes of Castigant, then you’re really in for some holy rolling). Whether this game represents a good choice for you spiritually is very case by case, but if you are part of the specific demographic of “Catholics who play JRPGs and do tabletop roleplay” then I’d say it’s worth taking a look if you are interested (SpicyFoodHiccups cried, “There are dozens of us! Dozens!”). The author’s foreword gave a mission statement about how Fabula Ultima was written as an antidote to the endless streams of dark fantasy nihilist work in this hobby’s space, and I for one think it was quite convincing considering how central the theme of heroism is. We may disagree on the necessity of distinct eternal outcomes to truly defeat such nihilism, but I can admire fellow fighters against such darkness all the same.

Score: 90%

Gameplay: 4/5

Layout and Art: 5/5

Writing: 4/5

Replayability: 5/5

Morality/Parental Warnings

The precise contents of any Fabula Ultima TTJRPG game are ultimately up to the players involved to decide, but I shall endeavor to point out elements written in the book which might give readers some pause. The most immediate thing to identify is the prescription of an animist Stream of Souls as the spiritual backdrop of any world you create, thus encouraging an unjust afterlife wherein all are eventually obliterated and recycled. This Stream also serves as a blanket explanation for the various magics and spellcasting in the game, absolving all magic of any discussion of whether it is good or evil by giving it the same fundamental source. You may of course defy or loophole the animist framework if you’re feeling bold, but that is not the intended design. Magic is also easy enough to rewrite if you want to, although you will probably need some degree of supernatural effects in your setting if you want an easy explanation for the elemental damage types which are essential to the game’s combat system. Of the three supported “fantasy” types in the system, Techno Fantasy bears elements of darker cyberpunk themes, but it is optional and can be omitted from your game.

One of the emotions you can attach to a Bond that you develop is “Hatred”, and there’s even an entire class called Darkblade which can be built around weaponizing that hatred into dark attacks. Characters run around with all manner of weapons from swords to guns to mystical staves, but things only get as graphic as you allow it to be. Some of the sample recommended Themes are things like Anger or Vengeance. The game also uses pronouns in place of declaring sex or gender, which might be obfuscating for younger audiences. There are a total of five different magic-based class disciplines you can choose for a character, and some feature more spooky thematics than others like the Arcanist’s binding and summoning of entities or the Entropist’s chaotic void magic. A few of the flavor quotes in the class section are a little suspect, like the Rogue’s “I will find my own justice.” Some of the game’s sample rare items reference real world mythology and the occult, such as a bow named “Artemis” and an arcane weapon named “Ars Goetia,” although their literal translation of such legends is dependent on the group. Undead creatures and “demons” feature in the game’s bestiary, and the entire class of “demons” are described as “beliefs made manifest” rather than the true sense of the word.