The Etrian Odyssey Origins Collection was an exciting return to the roots of Atlus’ iconic dungeon-crawling series, and for me personally a chance to play the entirety of the original trilogy for the first time. I was very eager to jump into Heroes of Lagaard directly after revisiting the maiden entry, but if the gap between that review and this one tells you anything it’s that the prospect of rounding out the journey was… unusually challenging for me. This is because today’s title has an incredibly strong reputation among the Etrian Odyssey community, and in all honesty I was worried. Was I going to enjoy this pinnacle and have my perspective on Etrian as a whole transformed, or would the shadow of its legacy conceal something that I couldn’t see the appeal of? After more than a year of procrastinating, it is finally time to give my answer.

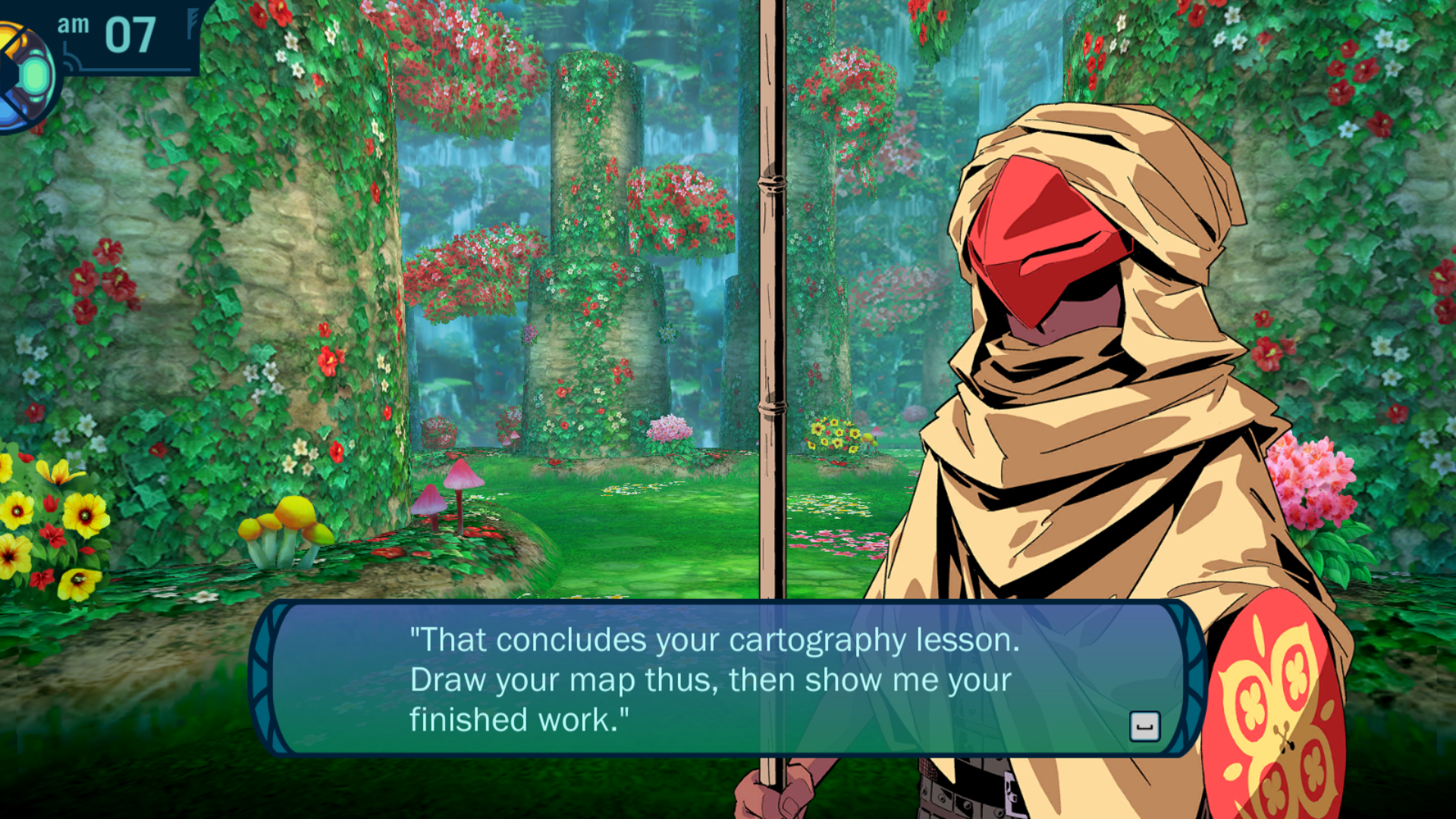

Developed and published by Atlus in 2010, Etrian Odyssey III: The Drowned City is a cartographic dungeon surveyal RPG, released initially for the Nintendo DS and later remastered for PC and Windows in 2023. Its premise involves a guild of explorers diving into a deadly labyrinth to find a sunken city district, and navigating their way into a conflict much more complex than they could have foreseen. Players interact with the game by reading dialogue, managing a guild of explorers, fighting monsters in a labyrinth, and drawing maps. Please note that the game was played on the Steam HD remastered edition, and version differences may arise.

The story of Etrian Odyssey III: The Drowned City, sees the player arrive in the ocean city of Armaroad, located on an island under the great tree Yggdrasil. 100 years ago there was an event called the Calamity which caused a portion of the city sink into the depths of the sea, which has now become known as the Deep City. The only way to reach the Deep City now is through the dangerous Yggdrasil Labyrinth, which none have been able to conquer. But your guild is here now, and perhaps you’ll be the ones to rediscover the Deep City and witness the truth of Armaroad for yourself.

Right away we see that this new entry sets itself apart from its predecessors by being entirely standalone, lacking any non-cameo references to the town of Etria or the Grand Duchy of High Lagaard. While it does technically take place in the same universe the tale is thoroughly its own, and this will become a fixture of the series going forward. I personally will miss the unique sense of continuity that exists between Etrian I and II, and hope that perhaps one day Atlus will consider doing another duology in the same vein, but I can understand the desire to give this game and the other future sequels more space to pursue their own ideas. As usual The Drowned City is perfectly happy to simply let its plot marinate in the back for a while before giving you a better picture of what’s really going on, but this entry in particular starts building a heavily involved narrative backdrop much sooner than the previous games. Even more impressively is that this story is technically built up to as early as the first stratum, as a subplot within the early game serves as major foreshadowing for how the game is ultimately going to play out. It may not have the same cutscene density of other RPGs, but Etrian III is definitely the most narrative-driven entry thus far.

As for the narrative’s quality it’s difficult to really grasp at my full thoughts on it without getting into spoilers, but for now I’ll try to be vague and say that it is good but it might be a bit too out of step with what came before. The most iconic feature of the game’s campaign, its multiple routes, does a good job at paying off the game’s themes and gives players an engaging dilemma to further invest themselves in the story, in addition to giving New Game+ more value. At a base level the worldbuilding is more detailed and should for all intents and purposes be the most epic saga in the series. For me though I think the story eventually starts to lose me when halfway through the game it becomes apparent that the Yggdrasil Labyrinth is less of an enigma than it first appeared. While Etrian Odyssey stories have always featured characters who secretly know the answers to the main mysteries, the nature of The Drowned City’s labyrinth becomes so much of an open secret amongst the power players that the story loses the adventurous feeling which is so essential to the appeal of these games. It’s the empty hole left by this decision which really leaves me conflicted about the storytelling, as while it successfully weaves the most fleshed out narrative so far it comes at the cost of the core fantasy I went into the game looking for. Perhaps it’s my fault for not meeting the game on its own terms, but this conflict dwells within me nonetheless.

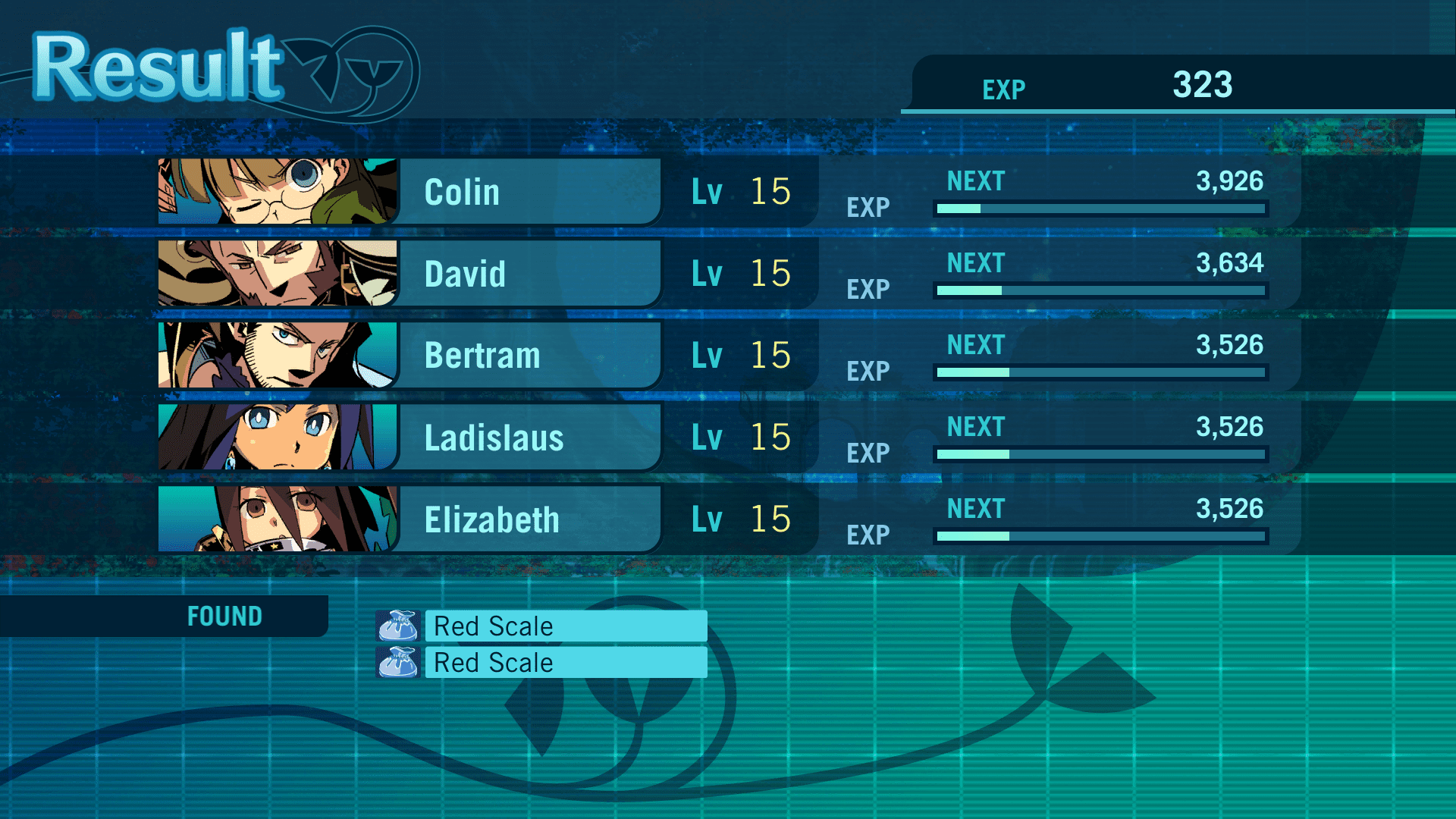

As for the gameplay, Etrian Odyssey III retains the fundamentals of its predecessors whilst challenging the player to relearn the systems through a totally new set of tools. Every single class in the game is brand-new, with ten playable archetypes to choose from at the beginning of the game. The variety on display is impressive and the various classes each have novel abilities that make them fun to use, however the large roster does ultimately end up being a pretty noticeable issue for first-timer onboarding. Etrian Odyssey II was able to get away with a large roster of initial classes by virtue of the fact that its identity as a sequel was embraced fully, but with III trying to be more standalone these ten options serve to make constructing a well-composed party extremely difficult without outside information. In particular you might hear that any party combination you can think of works (within reason) online, but in practice this is really only the case after you unlock sub-classing after beating the second stratum. The first two stratums by comparison feel like they borderline require certain classes to beat, and the huge number of options makes it extremely difficult for the game to guide you towards actually assembling that core team. In particular the Prince/Princess and its passive healing abilities dramatically alter the difficulty of the early game, but with ten classes to pick from and only five active party slots it’s a literal coin flip as to whether you’ll even choose to pick this most crucial asset if you don’t already know about it. It’s also worth mentioning that the two unlockable classes only open up deep into the campaign and are each exclusive to the two main story routes, meaning that casual players won’t really have much reason to disrupt their party composition just to make those newcomers work.

Once you do understand how these character classes fit together into a core fighting engine, I’d honestly say that the play patterns encouraged by most of them are among some of the least interesting in the series. There are a few exceptions like the Monk class, which is designed with the frontline healer/dps hybrid build in mind such that playing a Monk involves an engaging dynamic of choosing whether to spend each turn pressing your luck with more bare-knuckle beatdowns or focusing on supplementing your Prince’s healing output. But then you have classes whose optimal strategies are just frustratingly simplistic and passive. The Zodiac as the spiritual successor to Alchemist should provide the challenge of TP management and careful skill point allocation to maximize its weakness-exploiting potential, but why would you bother with such strategic play when you can just spam Dark Ether on your front line and extract an insane amount of value from allowing the vanguard to spam their strongest moves over and over? The Hoplite in theory should be a fresh take on tanking that sees it move between the front and rear lines to block wherever they’re needed most, but this is so cumbersome to do in practice that the better strategy is to just draw the enemy’s aggro with Provoke and hope your parry skills randomly nullify damage whilst you spam Blitzritter. Perhaps this is more a symptom of my particular party composition and the game might have been more fun with a different loadout, but it’s hard not to notice that many of the best skills are ones that are passive and it’s simply less engaging to me.

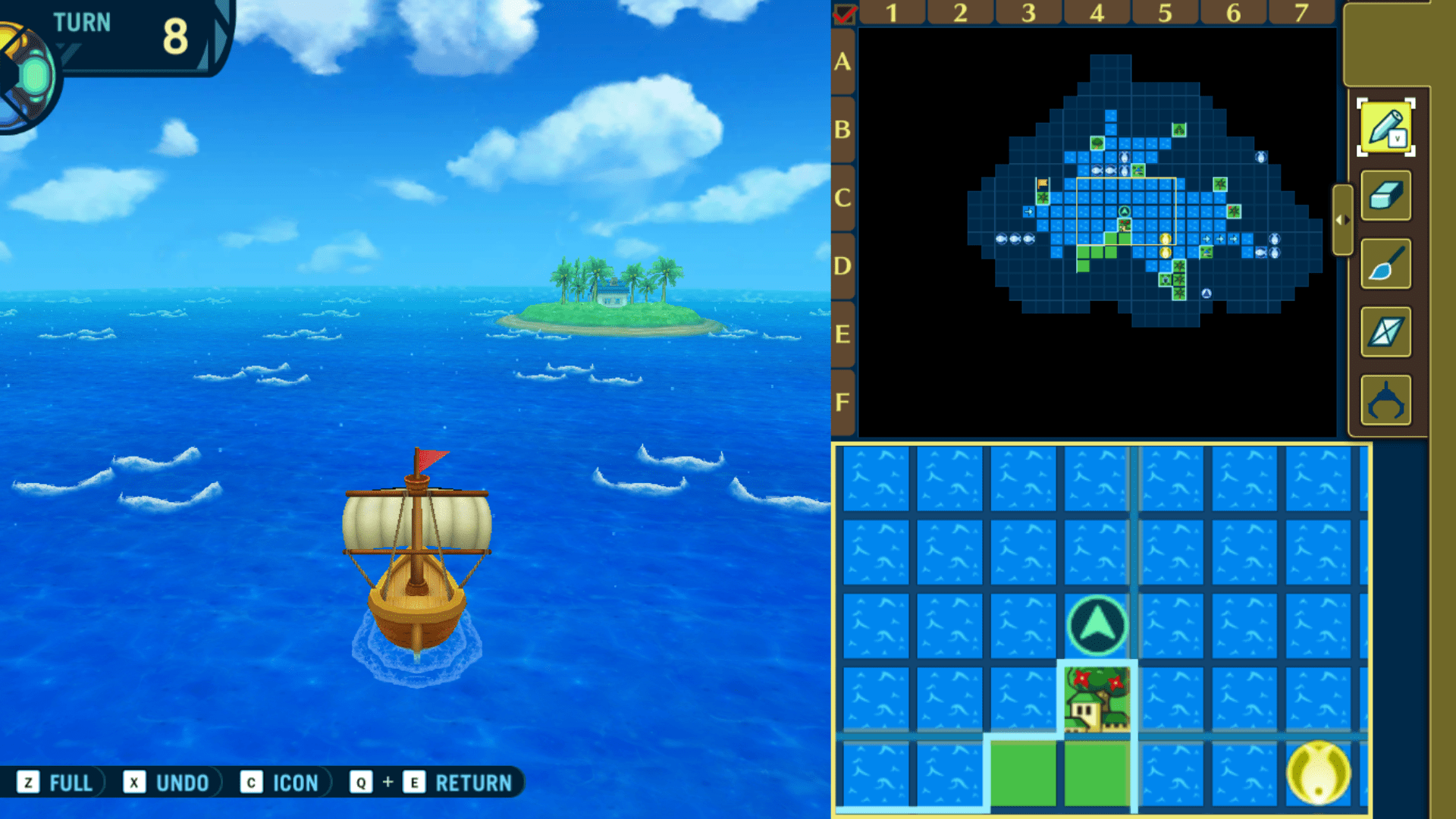

As for the core gameplay, The Drowned City retains the same general battle and dungeon system from the previous games, and instead focuses more on structural overhauls. The biggest change would be the dungeon having a total of 20 floors to beat the main story instead of 25. This is likely the case because a decent chunk of the memory space was used to create the sailing expedition mode, which sees you setting out to complete quests in the oceans around Armaroad and map the archipelago that was scrambled by the Calamity. On paper this seemed like a unique way to have EO III stand out from its contemporaries, and I will give the game some credit for its core dungeon challenges. The navigation puzzles in the 4th and 5th Stratums are some of the most challenging and fun ideas I’ve seen in the series thus far, and the 2nd Stratum has an incredible layout that essentially sneaks in a fifth floor via a maze design that wraps around itself. Unfortunately for most of the game four floors are all you get, which would be fine except for the fact that enemies are scaled in difficulty at roughly the same pace as the previous games. This means that progressing through the campaign is an arduous procession of difficulty spikes that you just have to power-level your way through. Not even attaching bonus exp to the completion of side quests and main missions really mitigates these problems. This leaves the sea exploration to fill in the gap, right? After all, it’s a major new feature that hosts many bonus quests and optional boss fights to help you even out the leveling curve right?

Well this is where I admit maybe the most embarrassing thing I’ve ever experienced working on one of these reviews for the site: I could not for the life of me progress in the sea exploration mode. The main limitation here is just how punishing the mode is, as it costs money to even start sailing and you can only sail for a certain number of moves before being booted back to Armaroad where you have to pay more money to explore more. Money in Etrian Odyssey games is scarce as it is, and constantly throwing it into a side mode for minimal returns on investment is hardly an appealing prospect. I know that the item upgrades I need to progress are somewhere out on the waves, but honestly I can’t see how I would find everything without either an online guide or a lot of note-taking outside of the game. The sad part is that none of this had to be the case, as I think this issue could have been solved by making some of the side quest rewards better sailing items, thereby creating a harmonious relationship where progress in the labyrinth makes sailing easier and vice versa. As it is now the sailing in EO III is just an obtuse and frustrating aspect of the game that punished me heavily for not gambling away money in the hope that maybe this time I’ll find the right island in the middle of nowhere. Call me a filthy journo who can’t play games all you like, I still think it’s dumb.

Overall The Drowned City probably has my least favorite gameplay in the series to date, as while the individual pieces of the Yggdrasil Labyrinth are some of the most interesting iterations of the core gameplay, it’s surrounded by design decisions that are hostile to the natural progression curve one would expect. Honestly I have half a mind to forgive Heroes of Lagaard for its lack of FOE exp after seeing just how much worse an effect cutting 5 floors out in favor of a wonky sailing minigame has on the pace of the game! The character building is also at a low point too, with many classes devolving into fairly uninteresting builds despite their unique themes and more ambitious ideas. At the end of the day it is still Etrian Odyssey gameplay and if you like the series’ gameplay then you’ll definitely get some enjoyment out of it, but when most of the significant gameplay changes make the game less fun overall it’s hard to not focus on the negatives while discussing it.

Presentation wise, The Drowned City is about on-par with the previous entries. Character portraits have settled into the more dynamic style introduced in EO II, but customization has been further enhanced with alternate color palettes for every portrait. This means we’ve essentially doubled the number of options, and this even includes the extra portraits made for the HD version. NPC and enemy art is good as always, with the town backdrops in particular being quite varied and interesting. Unfortunately the labyrinth itself is kind of a miss for me visually, as aside from the vibrant 1st stratum and the captivating 5th stratum, the theming winds up being quite desolate in its aesthetics. It works for the ocean vibe to be sure, but compared to previous entries that desolation loses impact when it’s the rule rather than the exception.

As for the music, it’s probably my least favorite soundtrack of the Origins collection games but it’s still pretty good. My main hangup is that the exploration themes don’t quite hit the atmospheric heights of other games, as those were often my favorite tracks, but I suppose I’m just nitpicking about how these songs aren’t as good as actual kino. One piece of particularly high praise I have is for the first battle theme, which might be the greatest fight theme in the whole series… making it all the more disappointing that it’s retired from the 3rd stratum onwards in favor of a still good but far less impressive track. At least the town themes are pleasant as always!

Lastly in terms of what we can take from Etrian Odyssey III spiritually, I think the best use of our discussion would be in analyzing the route split and all that it entails. Spoilers for pretty much all the major mysteries of the game, so you have been warned. After the 2nd Stratum you discover that the initial quest to find the Deep City is already complete, and from there delve into the true conflict of the game. It turns out that the Calamity happened because the last king of Armaroad, now known as the Abyssal King, heeded the call of Yggdrasil itself and sank what would become The Deep City in order to combat the Deep Ones, servants of an evil power that Yggdrasil has been fighting for a long time. Believing these beings to prey upon human emotions for power, he isolated himself and waged a lonely war against the Deep Ones with an army of automatons, whilst in Armaroad above his left-behind sister The Porcelain Princess wishes to reunite with her brother and take Armaroad’s fate into humanity’s hands. Soon after you’re made to make a choice between helping either Armaroad or The Deep City’s interests, which symbolically is a choice between facing evil with a mistrust in human emotions or a commitment to fighting in spite of human vulnerability. Who is right here?

From the Catholic perspective this could be taken as a musing on human nature and sin, namely a question of why do we have emotions when they make us vulnerable to sin and disobedience to God. It’s very tempting to imagine a world where a lack of emotions would lead us to be perfect in our behavior, never swayed by passion to stray from the straight and narrow, and yet the evidence of our own lives proves that God chose create us with emotions, with even the Bible being full of commands for us to rejoice. Further still we can know that God Himself, the one perfect Being, has emotions like love and sorrow, which suggests that it is better and more perfect to have experiences of emotion than to not have them. In light of this, while the Abyssal King might be technically correct in saying that human nature leaves us more vulnerable in the fight against evil, there is still an undeniable necessity and nobility in facing evil for ourselves. The denizens of The Deep City also demonstrate the dangers of lacking emotional grounding too, as during the early stages of the game they coldly lead adventurers to their deaths in the labyrinth to prevent them from reaching the levels where the Deep Ones reside. A rational strategy for the Abyss King as far as maintaining his plan of action, but it makes him into a walking contraction who claims to be fighting out of dedication to mankind yet kills the very people he means to protect in pursuit of that end. It might be a tough call to make, but our emotions are as much a gift from God as our reason is, and only by siding with Armaroad do you truly show gratitude for both. We do indeed have a responsibility to manage excesses of emotions that might cause us to sin, but it is as important to allow our hearts to embrace those movements of spirit which drive us to greater heights of virtue.

But no conversation about Etrian Odyssey III’s endings could be complete without discussion of the third path, so allow me to briefly touch on it. Many would argue that the third path is the correct choice since it leads to the best outcome for all parties involved, but I’m of the opinion that this ignores the means by which this is achieved. To even gain access to this route you need to engage in oathbreaking and manipulation earlier in the game, which is clearly a terrible thing to do. Then after that you need to parley with the head of the Deep Ones and strike a bargain which directly empowers them before starting the final stratum. As we’ve established that the Deep Ones are symbolically manifestations of sin and evil in the story, this gives the entire proceeding a deal-with-the-devil undertone. At best you can read this as the Eldest One trying to amend the suffering caused by his earlier deal with The Porcelain Princess, but if that were the case why does he immediately challenge you to a fight to the death to determine the fate of Armaroad? (As an aside, yes the Princess is in the wrong herself for compromising her humanity in bargaining with the Deep Ones, but that’s a little beside the point.) The true ending is just an out-and-out mess as far as morality goes, a long string of questionable decisions and sinful non-sequiturs that just happen to work out for everyone in the end. By now I’ve pretty thoroughly established with my readers that you can’t do evil in pursuit of good, so I’ll leave it here for today. End of spoilers.

In summary, Etrian Odyssey III: The Drowned City was unfortunately a sour note for the DS era of games to go out on for me. Many of its new ideas are solid in a vacuum, but taken in sum almost every corner of this game has issues that lead to an experience that heavily punishes you for not knowing obscure information, with story and world-building that feel too incongruent to Etrian Odyssey’s core appeal. This game exists in a strange middle-ground where its biggest potential audience is made up of either metagaming Etrian diehards who love a good challenge, or prospective new fans turned off by other titles in the series who might appreciate its unique features more. But for most other players, I would consider it the game you get for free in the Origins bundle whilst paying the price for the other two games. Play the game if you have it and maybe you’ll be less harsh on it than I was, but I for one couldn’t help being massively disappointed in The Drowned City. I’m glad I got to play this final adventure of the collection, but I’ll be taking the first boat elsewhere.

Scoring: 68%

Gameplay: 2/5

Story: 3/5

Art and Graphics: 3/5

Music: 4/5

Replayability: 5/5

Morality/Parental Warnings

Etrian Odyssey III: The Drowned City features a few mythological and supernatural elements. Enemies in the game are typically made up of oceanic wildlife and typical fantasy monsters but a few draw mostly benign ties to myths, like the Deep Ones being based around merfolk (shapely bodies included). Some are a little more terrifying than others. Two of the major entities in the story are referred to as gods, sometimes even with the capital G, despite the fact they are evidently not particularly divine. Among the player’s available classes, the Monks are based on eastern martial spiritualities like the manipulation of ki, the Zodiacs are astrologers who draw elemental magics from the stars, and the Wildlings take inspiration from tribal shamans. No magic is portrayed in practical manners at least. The game’s story features principle characters who sacrifice great parts of their humanity in pursuit of their goals, both to the aforementioned ‘gods’.

Violence is portrayed through still images and particle effects, so though most characters wield a variety of weapons nothing especially graphic is shown. Some descriptions given during quests can get bloody, but it’s not visualized. The player has full control over the modesty of their party’s clothing, but there are certainly a number of portraits you can choose from which are quite risque. The characters’ ages are also ambiguous, which might make some of the art more or less bothersome. Beyond the party you will also regularly encounter the townsfolk Missy and Napier’s sister, whose outfits are fairly revealing. Foul language is relatively uncommon, but still present in the script. Getting the true ending involves being a liar and dealing with a dark entity.