This review was made in gracious collaboration with Top Notch International and you can buy the game through the Kickstarter link here.

One of the primary purposes of alternative TTRPG games in the broader tabletop marketplace is to offer unique experiences that draw from more genres than your typical game of Dungeons and Dragons. There have been plenty of options for the likes of science fiction and cyberpunk since the hobby’s initial surge in popularity, but the modern resurgence of tabletop roleplaying has pushed the boundaries out into games that get very particular in where they draw their inspirations from. Today’s title aims to capture the appeal of one of the 2010s’ most explosively popular genres of anime, and I’m here to share just what came of those efforts. The new world is before you, so heed my guidance before your smartphone battery runs dry!

Helmed by Andrea Ruggeri, published by Top Notch Internations, and successfully kickstarted on September 22 of 2024 with a physical release arriving soon, Gates of Krystalia is an isekai TTRPG available currently on Kickstarter. Its premise involves players assuming the role of heroes summoned to a fantasy world where they must gather renown and riches alike to grow their settlement and carve out a place in their new environment. Players engage with the game through roleplay, using playing cards to determine their performance in clearing tests, fighting monsters, haggling with shopkeepers, finding materials, and deepening relationships. Please note that I primarily used the 1.4 version of the english pdf and changes may come in the future along with differences in the physical copies.

Foundational Rules

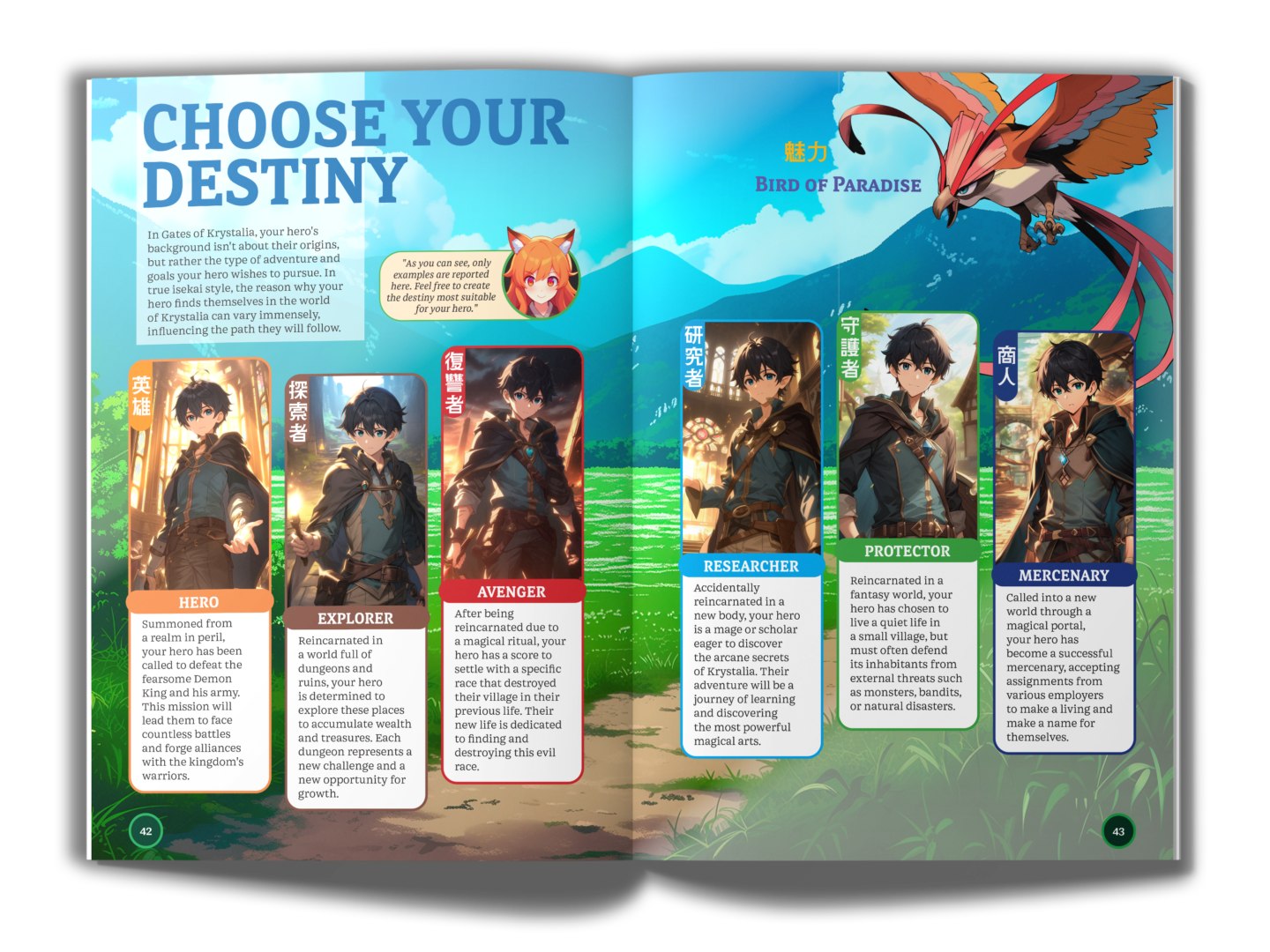

This review will cover the contents of the book in roughly the order of appearance, skimming over the introduction as most of the information there is reiterated in more detail. One thing to note immediately though is that the table of contents and the page numbers are often either in green or red, and these delineate mechanics which the designers consider basic and advanced areas of the rules respectively. This gives the game a level of immediate customization where the table can decide to start the game off as a simple “combat n’ checks” affair, and gradually incorporate more punishing mechanics or involved downtime activities as the game becomes more familiar to them. The first step in playing Gates of Krystalia is having the players create their heroes through a series of choices. The first thing established is what Rank the game will be starting at, from the basic Heroic Rank (one) all the way to the fully-featured Legendary Rank (four). This serves as the game’s progression system, and is thoroughly at the Game Master’s (Deux as the game refers to them) discretion as there’s no exp to speak of. This system naturally lends the game to a more narrative driven pace to power scaling, which means groups dedicated to playing out every Rank for their campaign can decide for themselves how long the game lasts compared to more jealous experience systems.

Next the players select a race and a class, which affects their base stats and affords a number of unique abilities. These obviously provide a good chunk of variety to how each hero plays, but there does seem to be more overlap here than one might initially think. For example you gain both of your race’s Innate Abilities by the time you hit Valiant Rank (two), so your choice of a race perk becomes less of a trade-off over time unless you opt to instead take one of the advanced Generic Innates at Heroic Rank. Classes are more upfront about simply giving you two abilities (called Specializations) but you may want to read them carefully as while these are all pretty different from each other, some class abilities overlap with racial abilities. For instance you’d be forgiven for wanting to play an Astralis Healer due to how delightfully archetypal it sounds, only to realise that Healer’s Healing Light is just Astralis’ Celestial Light with one extra function and feel really awkward in that moment. Some of the classes can also feel unbalanced in ways that make me worried that some might be seen as strictly necessary in any given party. For example the Priest can use Divine Blessing during combat to count another player’s attacking card as any suit of their choice. This effectively makes it so that as long as the Priest doesn’t have any fighting techniques they specifically need to use, they can just rig the game’s randomness factor waaaay in the party’s favor for free (note: if this is a secret artistic design choice to convince the players of the almighty power of God and His servants on earth, then I 100% support the vision of this balancing). I certainly wouldn’t say I dislike the way race and class is handled here, but some better balancing and more Racial Abilities might make the game more replayable. Especially if a couple players find themselves drawn to the same race.

There’s a little more to character creation which you’ll see touched on as I go along, but now’s a good time to explain how Gates of Krystalia actually plays. Each player has a deck of playing cards which they can flip over to participate in ability checks known as Competency Tests, where clearing the target number equates to success. Each card is worth what it says on the tin, with Jacks, Queens, and Kings being worth 11, 12, and 13 respectively, and Aces being 14. You then add your ability bonus from your stats, adjust for narrative or conditional bonuses/penalties, and if the card’s suit matches the type of check (spades for intelligence, clubs for toughness, ect) then the whole result is doubled. These card checks retain the randomness found in dice, but give it a twist by making repeat results less common and encouraging more strategic uses of resting. This is because resting is the only way to reshuffle cards back into your deck, and the deck is also your health points. Thematically it’s quite genius insofar as it gives a concrete way to tell when a character is tired beyond simply accumulating wounds, and it makes pushing yourself to accomplish complex tasks more tangibly risky.

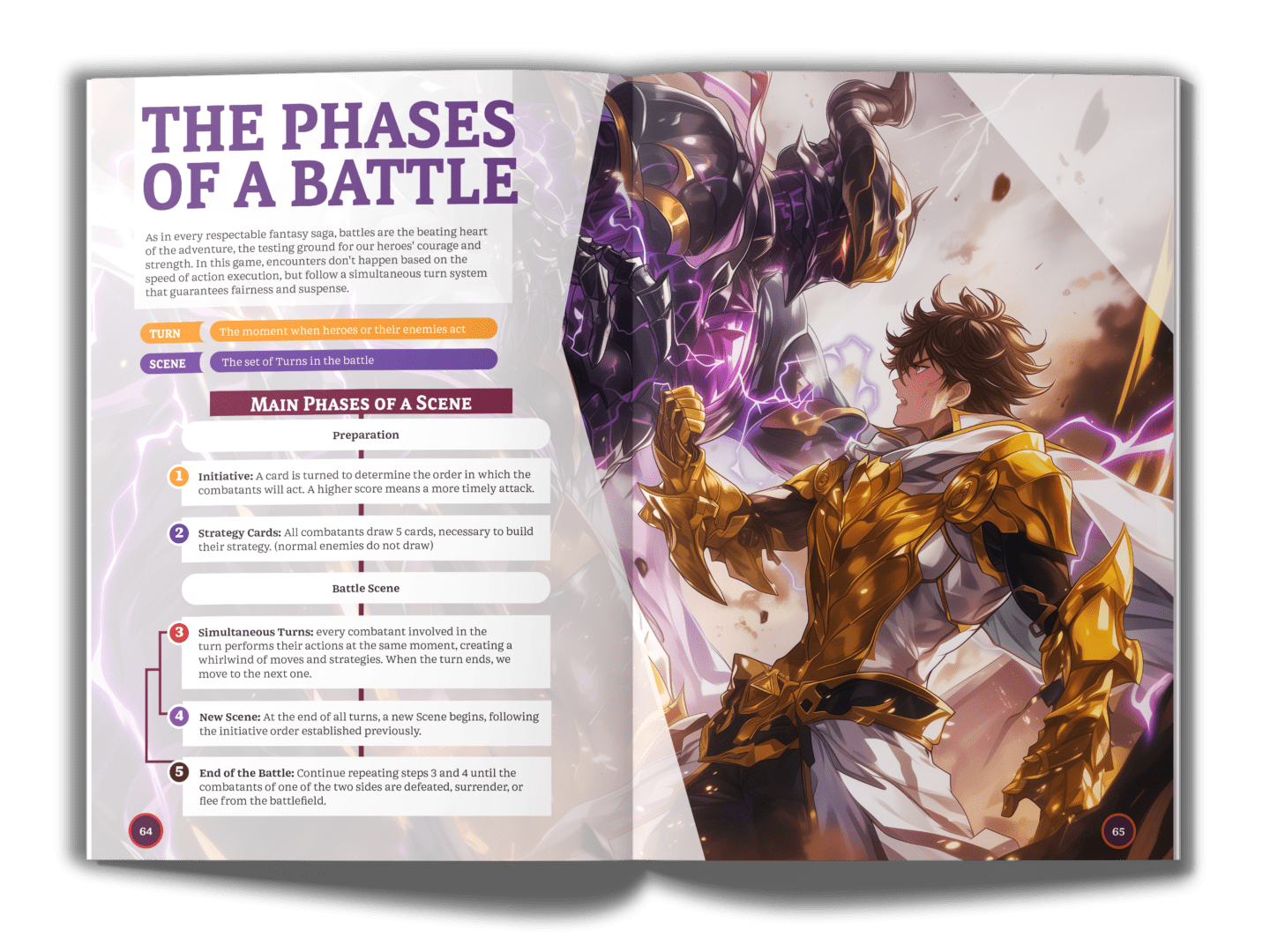

This is especially true for the combat section of the game, where you burn through cards much faster. In battle rather than simply drawing a single card, you draw a hand of cards which you can use to launch attacks with Combat Techniques on your turn or respond to attacking enemies during their turn (with those same Techniques). Combat includes further depth through the ability to create classic straights and pairings to increase your numbers, Blessed Seed bonuses chosen at character creation to double the damage of Techniques with matching suits (hello Priests!), and bonus effects that can trigger if you use face cards or aces. All of this utility comes at the cost of using up your hand very quickly, which not only leaves you helpless to respond when you need to most but also severely limits the variety of responses you can make given your suits in hand and such. A great example of the decision making involved here are the dodging self-buff techniques which when used with a face card basically invalidate an opponent’s entire turn, creating a dilemma of whether to use those valuable cards for defense or offence (especially since self-buffs must be used with their relevant suits).

This combat system does have some issues though. For one these Combat Techniques are in themselves an engaging part of building and leveling your character, but the basic attack Technique is a mandatory ability everyone needs on their sheet that is maybe the most useless of them all. Even if you can’t get a matching suit for some of the Combat Techniques, you seem to want to always use them anyways because the basic attack has no suit it’s blessed by, deals less damage than most other single-target attacks, and it’s only face-or-ace bonus effect is letting you use it again. There’s just no reason to spend your cards on something like this when you can use almost any other Combat Technique to get more damage and potentially get powerful bonus effects like status conditions, and an option as mandatory as this one shouldn’t be this useless. This in turn can make your other techniques and combat as a whole feel spammy too, though I guess Krystalia’s Blessing system does a decent job at combating this common RPG issue. On the GM’s side, controlling enemy actions aren’t too difficult but their ability to mixup encounter design is limited quite a bit by the card engine the game uses. Standard enemies top-deck for their actions while special enemies draw a hand and play like the heroes, and while you can fairly easily run multiple standard enemies from the GM’s deck it’s basically impossible to do more than one special enemy unless you’re a really organized person. Perhaps changing the abilities of the special enemies will do more to increase variety than I currently appreciate, but this does appear to be a limitation worth noting. All in all the combat has enough interesting and approachable design elements to be fun, but a mix of oversights and necessary evils do leave it with some flaws that could be iterated upon.

The last basic mechanic is the items system, which is mostly self explanatory but there are some things of note. The game is full of items of various types, from weapons to items that monsters drop to crafting reagents and more. Consumables give you expanded options in terms of moves you can make, while weapons affect the available Normal Type combat arts you can use, and armor can provide protection as one would expect (though curiously the low-level armors are the only ones that make a distinction between ranged and melee damage). Perhaps the most unique thing is that just about every piece of gear or consumable item has a recipe for you to craft it without buying it outright, and while some of these items require special workshops that I’ll get to later, this can actively save money for players if they are smart. You can dress like a nobleman for essentially half price if you make it yourself! The one issue I have with this system is how it relates to character creation, because the game offers you common clothes from the start and 50cc to get more gear but 50cc can’t even buy you a basic weapon. What’s so odd about this is that the sample starting character near the beginning of the book does have a weapon on him, but the step-by-step character creation rules never offer an explanation as to how he got it. It’s a strange oversight and I hope an update to the pdf will clarify this.

Advanced Rules

This covers all of the base mechanics if you want to play a simplified campaign, but Gates of Krystalia has a variety of advanced systems which add more involved downtime and greater challenge to the game. You aren’t expected to use all of the expanded systems, but you are encouraged to eventually use some of them given that aspects of the character options intentionally have interfaces with them, like the Dwarven bonus to forging tests. Speaking of, the first advanced rules are found early on in the character creation section. The first are the Generic Innate Abilities I mentioned earlier as a partial fix to the race homogeny issue, and generally include powerful new abilities that draw direct parallel to various isekai tropes. Next are the similar Hero Psychology options which grant you further bonus abilities based on the personality you wish to roleplay. On the other hand there’s the Corruption and Madness systems, which allow you explore the terrible price of wielding dark powers and the traumas of the warrior/adventurer life respectively if those are topics the group is interested in delving into. These are nice mechanics for those willing to keep track of a few more passive abilities, and the negative rules can make for a nice counterweight against all of the positive options the advanced rules offer.

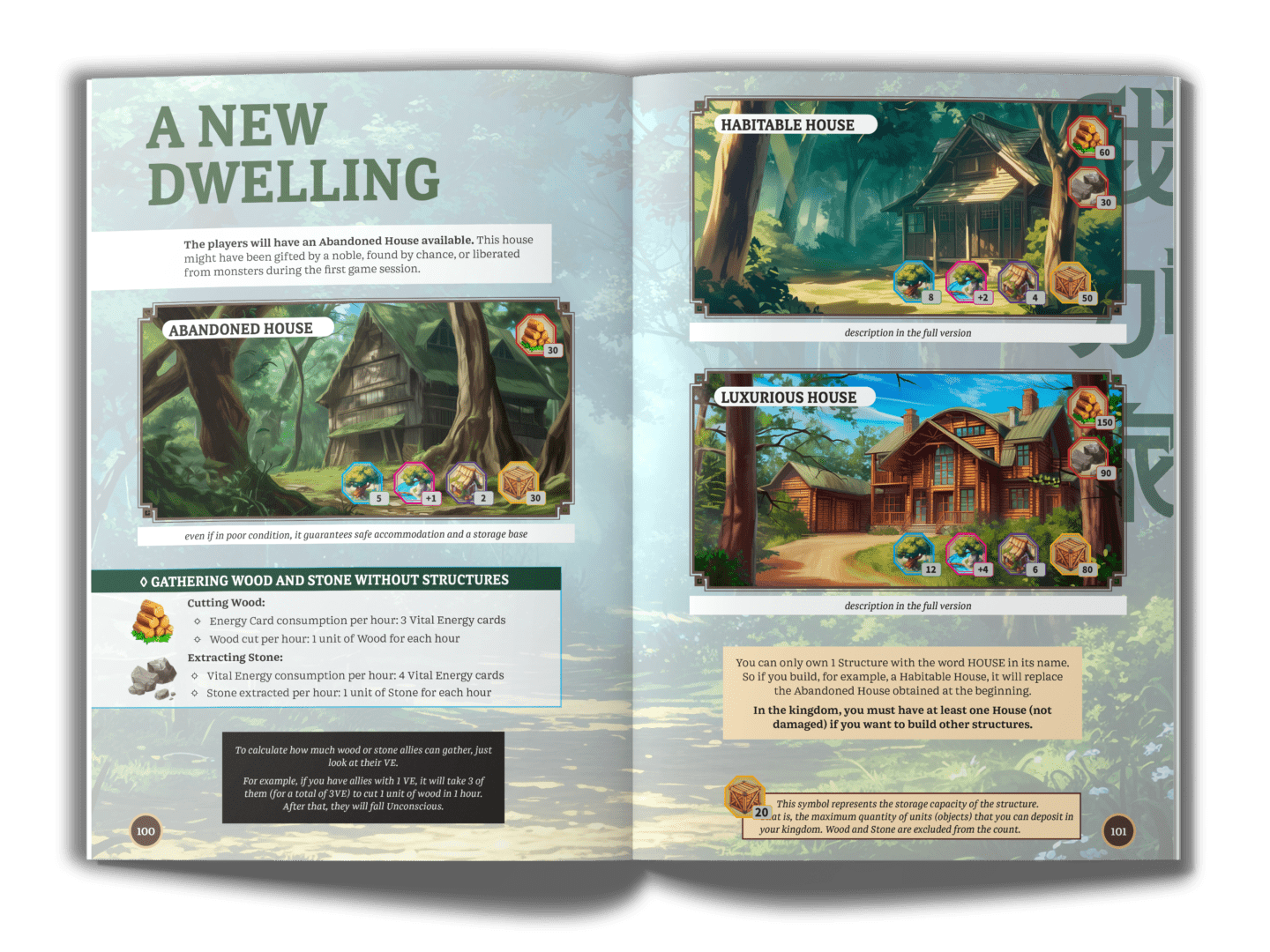

The rest of the advanced rules are more downtime focused, affording great rewards for great costs. There’s rules for joining an adventurer’s guild to get extra training and more lucrative jobs, and rules for the GM to manage ally characters not played by a hero (TOTAL God-send for me), but none are quite so in-depth as the kingdom building system. When using this system you start out with a house that provides storage space and a little room for allies, citizens, and personal belongings. Through gathering wood and stone through adventures, shopping, or just plain hard labor, you can build other structures like farms and workshops that increase both your kingdom’s maximum capacity as well as its upkeep costs, not to mention the ability to craft items you would otherwise have to barter or adventure for. Taken all together it’s a neat feature that basically serves as another soft leveling system, and I think captures that sense of building a new life for yourself which the isekai genre inherently speaks to. There is also the elephant in the room known as the harem mechanic, which as the name implies is designed to facilitate romantic relationships between the heroes and their allies. From a purely mechanical standpoint it works well as a way to reward bringing allies on missions consistently, and there is a rather tricky jealousy mechanic which does make monogamy a viable strategy. I’ll get more into this mechanic in a bit, but my one general complaint is that this system explicitly assumes these relationships are romantic, something that I find rather narrow-minded when good platonic friends can also help a hero resist corruption and make them look better socially. On the whole though, the downtime systems round out the game’s rules nicely for those willing to try them.

Other Non-Rules Topics

The last major sections of the book are a collection of monster profiles to take inspiration from and a gazetteer of the game’s base setting, Lumina. It’s a setting that gives easy context to your adventures, but it’s also not very detailed. There’s very obviously been a lot of room left to let the GM and players build their own kingdoms and flesh out the pocket worlds laying just behind the titular Interdimensional Gates in the capital city of Krystalia. If all you need is a setting to start playing I think it gets the job done, though personally I would work to create an isekai setting with a more complex and detailed state of affairs so I can immerse myself in a compelling world.

The actual book of Gates of Krystalia is probably where most of my issues with the product mostly stem from, as there has clearly been some editing troubles. Strange incongruities like with the starting equipment I mentioned earlier are way more common here than you might think: The base stat spreads for races typically display “0” for neutral scores but the Demons and Elves have “-”. The physical stat represented by clubs called Toughness in the book is called Robustness on the character sheet (a relic of an earlier version I believe). Competency Tests and Combat Techniques are both abbreviated to “CT,” which while not technically a mistake makes some sections more confusing to read. The Light and Darkness Crystal weapon effects have incorrect font coloring leading me to wonder what suits they actually interface with. The “(max +2)” for the affection Relationship Bonus is written twice. I understand an indie team trying to translate a whole book of rules on a modest budget can run into these kinds of issues and they can and likely will patch these up in the future, but I hope the print version has a good double check before it launches.

Then there’s probably what will be the most controversial aspect of this game: the AI art. Now to be as fair as I can, the developers have gotten the proper licenses they need for the art featured in the book, and the creators actively used editing to make sure that the art avoids the various eldritch horrors that AI tends to produce, so I will not dismiss the work that went into this production. Honestly given the reputation isekai currently has for being the ultimate genre of slop entertainment in the anime sphere, I would even go as far as to say that the somewhat bland feel of most pictures feels oddly appropriate. However it has to be observed that their desire to use this technology to fill the book with dozens of unique characters and background landscapes actually come across as incredibly overstimulating, leading to a book that can be hard to navigate when some of the text has to be placed in high-saturation color bubbles just to stand out. And in general I think the game might age poorly because visually it lacks that human touch which AI art simply can’t match even with the editing. If this book manages to generate enough profit, I would highly advise the team behind it to eventually release a definitive version that features a more concentrated amount of human art and cleans up the format so the text is more easy to parse. This will allow the book to be more user-friendly, and give it a visual identity that people will be drawn towards and inspire them in ways that human art alone can.

Like with most roleplaying games the degree to which Catholic themes can be drawn out of Gates of Krystalia is left up to the players, and to that end rather than having a massive spiritual deep dive here I’m instead going to produce a separate guide on ways you can bring out spiritually meritorious themes in an isekai roleplaying game. While I’m here though I might as well touch on the one element of the game that will raise the most eyebrows from prospective players: the harem mechanic. Harems are probably one of the most recognizable (though not universal mind you) aspects of isekai stories, usually included because they heighten the power-fantasy the viewer indulges in through the self-insert protagonist. After all if we’re already fantasizing about going to a world where your power is borderline peerless, why not include massive influence over the dating market too? Naturally this provokes all kinds of reactions from the anime community, from those who indulge the fantasy without thinking to much about it, to those who revel in the polyamory of it all, to those who find it cringy and uncultured, and to even a few with accusations of colonial undertones. What would the Catholic perspective take from this? Well if I had to narrow it down to any one thing, I would call this an infusion of pagan ethics into this particular brand of fantasy.

In the ancient pagan world the judgment of one’s character was rooted in strength and winning was the mark of a good man, and immorality wasn’t about what is bad for the soul but what ultimately weakens a man to the point of self-destruction. This was one of the many things that made Christianity so revolutionary at the time of its inception, as Christ taught us that true virtue came in mastery over our sinful desires and orienting our hearts towards The Good (aka God). Thus when we in a society founded upon Christian truth look upon much of the isekai genre’s legion of overpowered twink chick-magnets, we see the specter of ancient warlords and their concubines wrapped in a saccharine package. They may or may not pay lip service to real morality, but they are certainly engaged in anything but in the romance department. The chastity of saving our eros for one monogamous partner is without a doubt much harder than the alternative, but doing so provides a mastery over one’s self and a bond with your family that is unrivaled. Even the most powerful polyamorous isekai protagonist can’t match this level of love because he or she can never offer their partners the gift of true exclusivity, and all the material capacity to provide for their harem won’t make up for it. All of that is why if you do choose to use the romance rules I’d advise considering if you truly benefit from starting a harem at all, and work with the GM to make the pursuit of love more impactful in the absence of the harem-specific mechanics like Jealousy and Harem Harmony. There’s also nothing wrong with engaging with the harem mechanic as it is to eventually make a point that returns to the ultimate truth of monogamy’s superiority, but such an endeavor is highly group dependent and probably requires at least some coordinated effort from everyone at the table.

In conclusion, Gates of Krystalia is a game with many good and flavorful ideas in pursuit of the experience it wants to provide, but shows a few flaws in the final execution. The system plays fast and tactical with some very satisfying central mechanics, yet suffers chiefly from editorial issues which highlight some of its less well considered ideas. If nothing else I would encourage the interested to give it a read to experience both its more unique card system and the ways it cleverly tributes to the genre it pulls from, but you may find it prudent to wait for some further updates to clean up the product a bit before proposing it to your table. There’s fun to be had in this new world, but you might find yourself as uncomfortable as a shut-in dropped into the royal court before you truly find your footing in it.

If you’d like to try the game out for yourself there is a demo version available, provided you click the button on the official site and share your email: https://www.gatesofkrystalia.com/

Scoring: 60%

Gameplay: 4/5

Layout and Art: 2/5

Writing: 2/5

Replayability: 4/5

Morality/Parental Warnings

The content of any given game of Gates of Krystalia is largely dependent upon the group playing it, but there are some elements in the book to be aware of. As far as supernatural elements are concerned, players can choose to play as a demon or an oni when selecting their race, can learn a variety of dark-aspected Combat Techniques, and there is an optional corruption system that lets the players simulate the punishment for drawing upon dark powers (though that’s probably a health message to send). There’s also a Shaman class that binds the spirits of the dead to themselves and channels them to gain various boosts. The default assumption for the setting of Lumina is that the players are reincarnated into this fantasy world by a goddess introduced as Thenarix, and the built in end-game conflict is between a fantasy archangel and a demon king. Some of the Combat Techniques also make reference to vague gods in their name, implying a certain connection between those beings and the particular abilities. Many abilities in general are magical in nature, but they aren’t particularly described or used similarly to real magic other than maybe the aforementioned Shaman and things that could cause you Corruption. Additional setting themes with potential for other sticky subjects could be encountered via the Interdimensional Gates of Krystalia, like cyberpunk cities and limbo worlds. Combat involves the usual fare of swords, guns and spells but with no set visuals to speak of it only gets as gory as you make it. Enemies are your typical variety of magical animals, undead corpses, monstrous abominations, fiends, etc. A good chunk of the artwork for female characters is sexualized, with plenty of exposed skin to go around. The book’s most extreme piece of art is actually one of the very first ones you can encounter: the fallen-angel-looking character on the “what is a role-playing game?” page whose skimpy outfit leaves next to nothing to the imagination (amazingly the hot springs girl later in the book is arguably tamer!).