If you asked the average parent among the Catholic Game Reviews regulars why they choose to engage with our articles, chances are a good number of them do so because they appreciate that little morality warning section at the end. Who can truly blame them too, in this era where increasingly more radical ideas and depictions of sinful acts make their way from the B-list to the A-list entertainment media at a rapid pace? While it appears for the most part that our audience appreciates the work we do on this front though, there are occasionally those who feel we don’t go far enough and insist that we should review only games devoid of the many things that go in the morality section to begin with. These cries very much go heard by our little team, but as you may have noticed we haven’t exactly changed our policies on this issue. In today’s article I’d like to provide what I personally feel are the reasons why we feel comfortable with more mature content in the games we review as a part of our mission. The answers are perhaps simpler than you think, but they certainly may not be too obvious at first glance. Please note that this article is about my personal arguments and views, and may not speak for the entire staff of CGR.

The philosophical discussions surrounding the contents of stories are about as old as the practice itself. Plato’s Republic for instance, arguably the most recognizable work of classical philosophy for most people, covers this topic in great detail in Book III (far more detail than I have time to cover here). I bring Plato because I suspect most critics of art and storytelling on moral grounds take a similar stance to what is written in Book III, for he claims that his contemporary poets should not write about ordinary humans because “…what poets and prose writers say concerning the most important things about human beings is bad – that many happy men are unjust, and many wretched ones just, and that doing injustice is profitable if one gets away with it, but justice is someone else’s good and one’s own loss. We’ll forbid them to say such things and order them to sing and tell tales about the opposites of these things.” (III.392b)

Now, this quote by itself lacks a TON context regarding the project of the Republic when taken by itself, but I use it here anyway because I feel it reflects the fundamental worry at the heart of this issue: some people would write stories to promote that which is unjust. If the opening to this article tells you anything it’s that I and everyone at CGR acknowledges this, especially with how stories have tended towards being less pure and more propagandistic lately. It’s entirely reasonable to want to protect yourself and others from authors who spread ideas contrary to what is true. But where this line of thinking ends for most people fails to recognize one crucial aspect of this conversation: depictions of unjust behavior and the promotion of said behavior are fundamentally two different things.

To put this assertion into perspective, consider the Holy Bible. Because the Word of the Lord is sacred nonfiction, it has to depict the events of the past in order to get its message across. It’s also worth noting that projects such as The Great Adventure Bible Timeline have shown how truly narrative-like the Bible is when read in a certain order, so using it as a base is more relevant than you think. To say that grave evils take place in the Bible’s recollections would be an understatement: the murder of Abel, the adultery of David, the fall of Solomon, the betrayal and death of Jesus, and many others. Even the brief conversations that Lord Jesus had with the demons He exorcized are preserved within the pages of the Gospels. Does all of this make the Bible a deeply problematic and sinful book? Evidently not, and this is because all of these records exist for the purpose of teaching us right from wrong, and how to overcome these ills with the help of the Grace of God. In including details of grievous sin the Bible is not therein promoting sin, just the opposite in fact. Were humanity more godlike of mind we might have the capacity to understand right from wrong without such uncomfortable explanations, but in truth these darkened intellects of ours often need the aid of thorough explanations and illustrations (not always, but very often).

It is by this measure we can look at the poets from The Republic and condemn them not because they merely show injustice in their stories, but because they depict said injustices as profit. Conversely, a truly good storyteller can use depictions of injustice and sin as a staging ground for a tale of how justice ultimately conquered them. Make no mistake, there are certainly stories out that that follow in the tradition of making injustice seem profitable. Disney’s The Little Mermaid is an easy example of this, as when you really pay attention it’s a film about a rebellious teenager making a deal with the devil and ultimately getting away with it, sacrificing nothing and gaining everything she wants without learning any lessons. In contrast though, there are plenty of stories where the many ills that take place in them serve to properly teach us something of moral value. The 1968 film The Lion in Winter for instance, is about a fictional Christmas gathering between King Henry II and his family which devolves into political scheming that nearly ends in bloodshed. The level of family dysfunction on display is disgusting to say the least, but ultimately it is used to great effect in highlighting how the corrupting nature of power can tear people apart. Or perhaps consider The Song of Roland: it’s titular character is every bit as guilty of the sin of pride as the treacherous Ganelon, and despite how gloriously he and the other paladins fought and how touching his final moments are, Roland could not escape the disastrous effects his pride brought onto both himself and the many, many brothers in arms that died as a consequence. This pride is also juxtaposed against Charlemange’s humility, as even despite being the greatest king in the land he is absolutely obedient to the will of God as communicated by St. Gabriel, which more than anything is what makes him worthy of the great victories he achieves in the story.

When it comes time to consider the realm of fiction in video games then, the various acts of immoral character need not be harmful to depict in and of themselves so long as the narrative experience given is in service of a good that justifies exploring those darker aspects of the human experience. There are plenty of games I’ve already covered in other articles which could serve as good examples, my recent Trails in the Sky the 3rd review being a fine choice, but for the sake of variety I’m going to try a new example from Fire Emblem Three Houses. The following will spoil the game’s best route, Azure Moon, so skip the next paragraph or two if you plan on playing it for yourself.

The story of Three Houses’ Azure Moon route is fundamentally one about its main lord Dimitri Alexandre Blaiddyd, the way his past traumas catch up to him, and how he is ultimately saved from himself. Bearing witness to the brutal murder of his immediate family and closest bodyguards as a mere child, Prince Dimitri’s primary motivation for being involved at the Officers Academy is to gather information on the true masterminds behind the Tragedy of Duscur and exact revenge. When the player first meets the prince he comes off as the typical yet admirable protagonist type of character, and in many ways despite his dark secrets those virtuous qualities of his are truly genuine. But the game drops hints early on that not everything about this young man is so simple, and as the first half of the game draws to a close the player witnesses a much crueler side to their pupil. The climax comes when Dimitri’s trail of evidence leads him to conclude that the one he’s been hunting is none other than the game’s main villain and his step sister Edelgard von Hresvelg, with the shock subsequently driving him into madness. When the game picks back up after a five-year time-skip, Dimitri is nothing short of the series’ most broken protagonist, killing his enemies with psychopathic prejudice, seeing his allies as disposable pawns, and even hallucinating that the spirits of his dead family are urging him down his spiral of destruction, all for the sake of revenge. But even this darkness is ultimately overcome by the love of his friends and retainers, and in the game’s final quarter the prince resolves to live on for the right reasons and bring an end to the continent’s strife. He even holds parley with Edelgard in hopes of using the lessons he learned to resolve the war peacefully. This all culminates in Azure Moon’s final cutscene, which is one of the most sublime and heart wrenching moments I’ve seen in all of gaming.

At the risk of hyping it up too much, summary cannot do justice to how incredible I think the Azure Moon route is in its execution of a great redemption arc. But the tricky thing about writing effective character arcs of this type is that they are usually more impactful in proportion to how much detail the player has on the character’s past sins. The fall of Prince Dimitri is harrowing and painful to watch on just about every front, and yet the story clearly chooses to expose the player to it so that his eventual redemption and actions taken thereafter can hold immense weight in the player’s mind. So much of what makes the final act of Azure Moon and especially the last scene work is knowing the incredible tribulations, lapses in judgment and decisions which lead up to it, and it’s difficult to imagine this story written without them while still communicating its themes about with whom our duties lie and the courage to not give up on our humanity. Three Houses is just one of many examples where portraying the world’s injustices and fallenness can be used in service of a higher narrative good which strives to teach people how to be better.

But in giving this example, some may notice that I have elected to use a T-rated game, an ESRB rating which, while admittedly pushed out to greater limits overtime, usually is not emblematic of the content most parents and critics are truly worried about. Games intended for a 17+ age audience under the M-rating certainly radiate a kind of taste for shock value, which often smothers any meaningful narrative that could be told within. For a good example look no further than the game series which necessitated the creation of the ESRB in the first place, Mortal Kombat. Nobody needs an explanation of what Mortal Kombat is, because its reputation as a hyper violent gore-fest precedes itself. However, lots of mature games feature gore in them, and the real reason the series stands out as what not to do is because of how it uses its violence. No matter how much lore is added to Mortal Kombat, its fundamental selling point is the sick pleasure of getting to visit horrifically detailed murder upon your opponents, and everything in the games is subservient to that end. MK disgusts me because it fundamentally views sadism as the fun thing you buy the game for. Fatalities aren’t there to teach you anything meaningful, let alone good, about its characters and story, but rather the characters have been implicitly written as sadists to facilitate the fatalities, whether intentionally or not. But what if I told you that there exists another M-rated fighting game series which features graphic depictions of violence, but is used to tell meaningful stories?

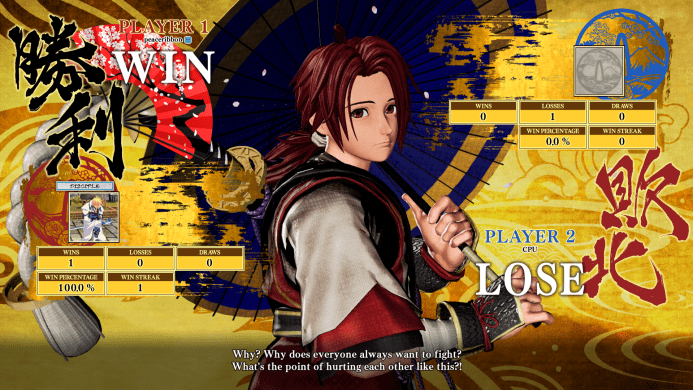

Samurai Shodown is a series of fighting games developed by SNK (the King of Fighters guys) since 1993. While it did eventually come to feature fatality-type moves in its fourth and fifth (in the “Special” version for the fifth) entries, thankfully omitted from the 2019 reboot, its violence is comparably concentrated in large spurts of blood, with only certain attacks cutting the opponent in half when used as a finishing blow. This artistic choice isn’t here just because the developers are slightly more squeamish than NetherRealm Studios though, rather it is because the narrative told through the gameplay focuses on the ones doing the fighting and why they choose to face the deadly path of the sword. To say that I think Samurai Shodown as a series is a redemption of deadly violence in fighting game form would be a bit much, as admittedly there aren’t many characters who I can name off the top of my head whose motivations for doing what they do is especially admirable. The main protagonist Haohmaru for instance, while certainly inclined to put evildoers to the sword, mainly fights for the thrill of facing powerful opponents and proving himself to be the strongest, which comes off as needlessly wasteful of human life depending on whether the match playing out on screen ends conclusively in the opponent’s death (it varies from entry to entry and you sometime have to parse it from context such and the finishing blow and the victory quote).

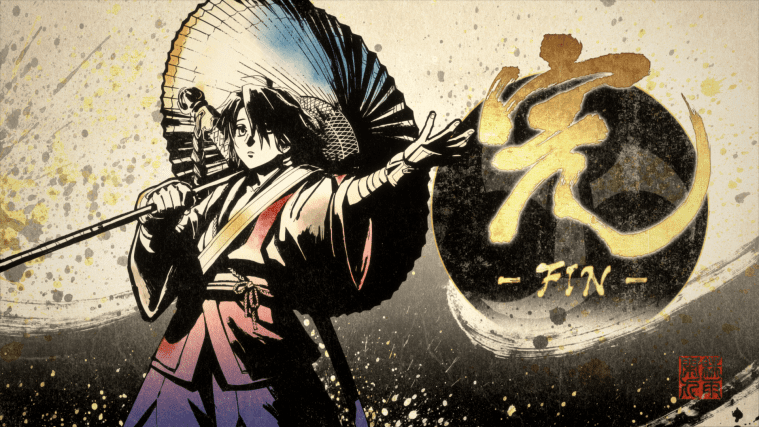

But in some cases, the characters in Samurai Shodown not only have compelling narrative reasons to fight, but are enhanced by the series’ more lethal take on combat. To demonstrate this, consider Shizumaru Hisame, the de facto protagonist of the third game and series regular from then on. Strikingly young, a partial amnesiac, and a lonely wanderer, Shizumaru was essentially cast out from ordinary life on suspicions of being a demon. Whether that is actually the case or not, he has internalized this suspicion about himself and travels to uncover the truth about what he actually is, and to control his strange feelings of bloodlust. In the gameplay itself he fights largely for the sake of self-defense, and despite carrying a sword his signature method of attacking is an umbrella. Umbrellas are tools with which we protect ourselves from the elements such as rain, but also a means by which the eyes can be shielded from things like bright lights or uncomfortable sights. Shizumaru’s use of an umbrella embodies both of these ideas, not only being a means of self defense for him but also serving as a barrier by which he tries to protect others from himself. Quite literally an alternative to protect his opponent from his sword. In the 2019 release when he unleashes his Issen attack, sure you see the opponent bleeding in the background, but the foreground is occupied by Shizumaru and the look of sadness he has for having to unleash such a powerful attack. His cinematic super might actually be the bloodiest in the game, but it barely focuses on the opponent’s pain, opting instead to focus on the boy ronin’s bloodlust overtaking him, and on the moments later when he comes to his senses and is horrified by what has just occurred. Seriously, it’s a masterwork of storytelling through gameplay.

What I love about Shizumaru and the way Samurai Shodown tells his story is because of how it wields the violence surrounding him to say something surprisingly life-affirming. In him I recognize the many reflections I had about myself in adolescence and how even in those days men can be capable of great harm if they fail to properly conquer those destructive temptations in their hearts. We also see in Shizumaru a maturity beyond his years that can inspire us, as he is fundamentally a gentle and kind person who simply seeks to “know thyself” and strives to truly conquer those dark parts of his humanity, exacerbated by demon meddling or otherwise. And by existing in a setting with consequences as dire as Samurai Shodown’s can be, we get to feel the great consequences of this war going on inside him more tangibly, and sympathize with the humane approach he employs wherever possible. The series’ use of violence may not be perfect, but there’s a real respect for the consequences of death which helps the player find serious contemplation about the subject matter on hand. And if you really want to, you can turn off the gore and dismemberment in SamSho 2019 if you desire to see those stories without some of its more sensitive material, although this definitely weakens the impact of the emergent storytelling. Personally I turn off the gore, though that’s mostly because by leaving it on I start trying to end the match without killing the opponent and subsequently play much worse. Nobody said doing the right thing would be easy…

But of course even after the many examples given in this article, I’m sure there is still a great division of opinion among readers on this subject. Perhaps some may feel that regardless of the narrative merits we should prune out sensitive content from our stories out of a desire for moral purity. But then one might argue that only telling sanitary stories gives the audience an infantilized picture of the world that doesn’t prepare them to face its sinfulness, so we should include sensitive material in order to learn about it in a safe environment. And then after that there are those who think such depictions have a certain threshold they cannot cross, and then others argue that depicting those things more accurately is important, and on and on and on. Basically every side here has valid points, and this leads us to the fundamental assertion regarding this topic which is reiterated by clerics and commentators alike all over the internet: it’s a matter of discernment and discretion.

While I think there are certain acts that are in fact too immoral to even attempt to portray explicitly (i.e. virtually no story needs to nor should depict the reproductive act to any degree which could flirt with pornography), for most injustices their use depends heavily on how the storyteller utilizes their portrayal, and further beyond the artist it is the responsibility and imperative of the individual members of the audience to decide how they are going to respond to the events of the tale. Many people are comfortable with the level of violence in the average Call of Duty game as apart of the warfare narrative, but those who sense that the gunplay would instill an inordinate love of battle in their charges or inspire themselves to wield a gun in immoral ways have a responsibility to avoid such experiences. Even a game like Persona 5, which is filled to the brim with gravely incoherent imaginings of spiritual matters and generally shunned by a lot of Catholic gamers, might still be within acceptable bounds for a player who knows they can look beyond the mythological gildings of the game and focus more on its symbolic commentaries about its characters and its society (I doubt there’s much of value here myself, but I wouldn’t deny somebody the chance to go looking if they’re mature enough to approach it sensibly).

Above all else, when a man is looking to play a game with potentially sensitive content it is important to understand the state of his spiritual life, and if doubts exist then he is called to meet with his parents or priest and talk seriously about what stories are right for him. If one is ignorant of the state of their soul and how stories will affect it, then one needs the humility to accept counsel regarding it. To leave off on at least one concrete piece of advice for those struggling with scrupulosity, I heard a great suggestion from a video on Youtube that stated if you’re asking whether a given activity is compatible with the good Christian life, you may already be asking the wrong question, and instead you should spend more time looking to ask what activity will best facilitate and enhance your Christian vocation. Perhaps this applies to which games you spend your allowance money on, too.

In conclusion, the depiction of sin and injustice with video games and stories at large need not be inherently wrong so long as the author uses those depictions to tell a meaningful story which promotes the good, but it is still very important that the viewer is aware of how he specifically will likely respond to a given tale and shift his viewing habits accordingly. At the end of the day, this is what we of Catholic Game Reviews have always strived to provide for our readers with the Parental/Morality Sections: an overview of the various moral depictions and/or failings which allows the reader to discern if the game in question is too much for him. Whether you feel this is an acceptable state of affairs is ultimately your own opinion, but I hope this article has given you an inkling of the reasons why we persist as a reviewer team. Games may not be a morally perfect medium, but that doesn’t mean they will never possess moral stories worth sharing, and by critiquing these tales maybe someday these reflections of ours will push developers and audiences alike to broaden their perspective and appreciate games which help people live more virtuous and fulfilling lives.

Special thanks to TheGoodHoms for offering a few words about The Lion in Winter. I uhh… don’t watch that many M-rated films.

If you enjoyed this extra spicy analysis of mine… well I can’t imagine such articles will be overly common. BUT if you want to help support the efforts of the site as a whole and help us continue to produce spiritually conscious game reviews, consider supporting us on Patreon. For a modest monthly sum you can help cover the cost of advertising and maintenance, gain exclusive stickers, chat with us on our official Discord, and even earn the right to request games to review!