An Exploration of Christian Themes in Final Fantasy

For 35 years, the Final Fantasy series has captivated gamers around the world, growing into a franchise with 15 main-line entries, numerous sequels, spinoffs, remakes, remasters, and even a few feature films. Final Fantasy’s intricate plots, beloved characters, memorable villains, as well as cinematic presentation, have made it an influential pillar of the JRPG genre. The games often involve ragtag groups of individuals banding together and saving the world from an ancient evil or toppling a megalomaniacal emperor figure. Such tales are nothing new to fiction generally, but for a series to have lasted several decades and become an institution unto itself, something deeper must be resonating with players.

Catholics might suggest that the reason these types of stories are so prevalent in fiction is because they point to truths about human nature. We sense that we are in a fallen world, and have a need both to be saved by Christ and to participate in His saving mission. The Final Fantasy games are no different. Each, to varying degrees, has a core that points to deeper truths. What follows is an exploration of some of the valuable themes that can be drawn out of the first entry in the series, appropriately titled Final Fantasy. (For a review, please see KMax’s excellent one from earlier this year here.)

Final Fantasy, owing to the limitations of the hardware available in 1987, certainly can’t match the level of dialogue and characterization of its more recent progeny. However, there is still a great deal of profundity to be plumbed. In particular, we will focus below on the three major elements of the story: the crystals, the villains, and the prophesied heroes dubbed the Warriors of Light.

The Crystals

At the outset, we are introduced to the game world’s four crystals, each of which is inherently tied to an elemental force driving the world: earth, fire, water, or wind. We’re also shown how each is failing, and that as their elemental forces weaken, the dangers to civilization grow. The earth decays, the seas rage, and monsters run rampant. (And yet somehow, amidst a veritable apocalypse, there remain enterprising citizens who find ways to run expensive shops in absolutely terrible locations, so it must not be all bad.) It’s a fairly simple setup for the story, but one that still resonates, and has some interesting Scriptural parallels.

The choice of a crystal as the focus of divine power does not seem accidental or surprising. Crystals are rare, ordered, and particularly beautiful when in the presence of a light to be reflected in their facets. They’re also rocks – unassailable materials that predate us, and will outlast us. These qualities are perhaps why rocks are used as symbols for God’s dwelling or activity in the world throughout both the Old and New Testaments. In Genesis 28, after God speaks to Jacob in a dream, Jacob “took the stone which he had put under his head and set it up for a pillar and poured oil on top of it. He called the name of that place Bethel” (meaning House of God). Exodus 17 recounts the story of God providing water for the Israelites through the rock at Massah and Meribah. Recalling this episode in 1 Corinthians, St. Paul writes, “For they drank from the supernatural Rock which followed them, and the Rock was Christ.” St. Peter also invites us to Christ with similar language: “Come to him, to that living stone, rejected by men but in God’s sight chosen and precious.” (1 Peter 2:4) Revelation is replete with crystal imagery, too. Recall that “before the throne [of God] there is as it were a sea of glass, like crystal.” (Rev 4: 6)

It does not seem like too much of a stretch, then, to see Final Fantasy’s crystals as symbols of God’s activity in our world, particularly through the person of Christ. For just as the crystals are suffused with the elemental forces driving their world, Christ is described both as a “living stone”, and also the One through whom “all things were made” (Jn 1:3).

Given that the central quest is prompted by the failure of the crystals, we may also read them as symbols of our relationship with God. With that in mind, the ways in which the crystals’ dwindling affects the world are of particular interest. The seas become more and more turbulent as the water crystal fails, just as our own lives grow chaotic and unmoored without Him. (“You rule the raging of the sea; when its waves rise, you still them.” Ps 89:9. “And he awoke and rebuked the wind, and said to the sea, ‘Peace! Be still!’ And the wind ceased, and there was a great calm.” Mark 4:39) In contrast, the winds die, just as we may be deaf to the movement of the Holy Spirit if we stray from God’s will.

Now, God does not fail us, but rather we fail him – and so too with the crystals in Final Fantasy. They are not losing their power on their own, but are rather having it stolen by Garland and his evil lieutenants.

Garland And The Fiends

Left to Right: Lich, Marilith, Kraken, Tiamat

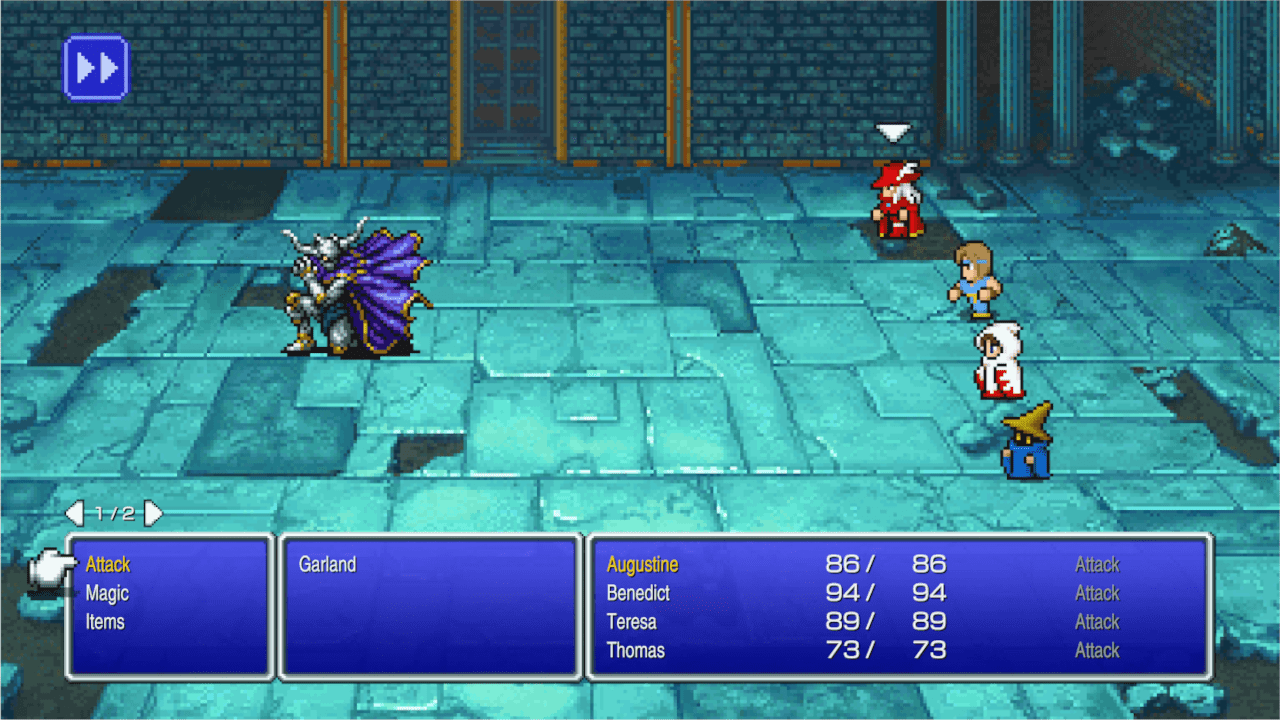

Encounters with Garland, Final Fantasy‘s principal villain, bookend the quest. Initially, the king of a land called Cornelia calls upon the player’s heroes – the “Warriors of Light” – to save his daughter from Garland’s evil clutches. Upon his defeat, Garland’s Fiends use the power of the crystals they’ve corrupted to send him back in time, where he can then safely send the Fiends out to corrupt the crystals in the first place, so they can be prepared to send him back again should he be defeated once more.

The Fiends deserve individual attention, as even with their sparse characterization and lore, each points to a deeper meaning. The first we meet is the Fiend of the Earth Crystal, Lich. Lich strikes an imposing figure as an undead skeleton wizard, and the land where he operates is marked by decay. He is also protected by a vampire who has stolen a relic from a nearby church. One might infer that the Lich is performing a theft of his own: stealing the life of the countryside to sustain his own bony being. Taken together, these could be seen as representative of gluttony, avarice, and lust – ways in which we trick ourselves into believing the penultimate goods of the world can satisfy our deeper need for the ultimate Good. The more we seek material, finite goods at the expense of the spiritual, the more we become like the Lich. Our bodies may persist, but we are spiritually dead. Taken to an extreme, this preoccupation with acquiring earthly goods can even be destructive to those closest to us, or the world around us.

The second Fiend is perhaps a little harder to classify, because we truly don’t linger around her too long. Marilith of the Fire Crystal dwells within a volcano, and all we are told is that, wherever she passes “all is engulfed in flame”. She could be seen as representing wrath – which should also be cooled as quickly as possible. All too often we find it easy to justify stoking the flames of our anger, assuming our own righteousness while willfully blind to the damage we might cause.

We encounter the last two in separate places, but the sages of Crescent Town describe them as a pair, which is handy for my purposes, as I think they form a better type together. The Kraken resides in a sunken shrine corrupting the Water Crystal deep within the ocean, while Tiamat waits with the Wind Crystal in an ancient civilization’s sky fortress. These Fiends both can be seen as typical of the abode of evil over which God has ultimate power. Water is perhaps more commonly recognized as symbolic of life and cleanliness, but in Scripture and the Sacraments, it can also symbolize the dwelling of sin – being drawn out of the water in Baptism is an efficacious sign of Christ saving us from evil. (Makes some sense – the seas are dangerous and bad things live there – not unlike the Kraken! Recall the first beast in Revelation 13, “rising out of the sea”.) Furthermore Tiamat, while in Final Fantasy often associated with wind, is in Mesopotamian myth a deity of the sea and primordial chaos. It’s fitting, then, that she be paired with the Kraken – but I think we can also appreciate the fact that Tiamat is placed in a geographically higher realm. Our in-game actions in the depths of the sea, and in the heavens, correcting the corruption of the crystals, can be seen as symbolic of God’s infinite and inexhaustible mercy. Nowhere is inaccessible to God, and no matter where we are, or what we’ve done, God is ready to heal our brokenness. See Psalm 103: “For as the heavens are high above the earth, so great is his mercy toward those who fear him” and Isaiah 40: “Every valley shall be lifted up, and every mountain and hill be made low…and the glory of the Lord shall be revealed.”

Finally, we have Garland himself. All we know is that he is a fallen knight, once famed but now consumed by power. He “lost sight of who he really was”. Once again, we can see in one of the villains a warning for us. Perhaps the most dangerous thing for a Catholic is to despair of God’s mercy, forgetting who we are as children of God, just as Garland forgot who he had been. Garland instead turns in on himself in a perpetual loop of hatred, only broken by the actions of the four prophesied heroes.

The Prophesied Heroes

If we consider the corrupted crystals as symbolic of humanity’s broken relationship with God, we can see the Warriors of Light as typical of Christ’s mission to restore that relationship. Initially, there’s even a fun bit of rhyming with Jesus’s earthly ministry. Before you set out to restore the crystals, you’re quite literally boating around a small sea healing the bedridden, reforming criminals, and restoring sight to the blind. These four heroes, long foretold to arrive in a time of peril, conquer various representations of sin and thereby put the world back in working order. Furthermore, the fact that they break Garland’s time loop lends an outside-of-time quality to their activities. So in short, we have long-prophesied heroes conquering manifestations of sin and restoring the crystals to grace once and for all…not unlike a certain prophesied Messiah who conquered sin once and for all in His sacrifice on the cross.

Typology Terminus

Final Fantasy, even with its relatively short quest, has quite a bit of value to be gained from an examination of its world of nefarious fiends, corrupted crystals, and the heroes who must restore them to grace. If, after reading this, you feel the same (and don’t feel like you’re stuck in a time loop of my making), I hope it won’t be long before an examination of the next series entry shows up here on Catholic Game Reviews.