Strategy role-playing games are a very interesting beast to unpack. Touted often as being a genre for those who enjoy thinking their way out of situations more than brute forcing them through mechanical skill, yet not quite free of the luck and numbers based variables that other games use for the sake of drama. As such their audience has often been rather niche, with the genre’s recent exposure being largely thanks to Fire Emblem’s heavy shift towards marketability (for better and for worse) in its recent titles. Nonetheless, there is a unique charm that this breed of game possesses, and today’s title is an earnest attempt to showcase that secret spice while also bringing ideas all its own. And if you’re expecting me to make fun of the name, prepare to be disappointed.

Developed by Artdink, co-published by Square Enix and Nintendo, and released in March 2022, Triangle Strategy is a branching-narrative tactical game for Nintendo Switch. Its premise involves the heir of a noble house facing a variety of moral dilemmas alongside his friends and advisors as his continent’s fragile peace is unraveled by secret revelations. Players interact with the game through grid-based strategy combat, town exploration, dialogue options, and branching narrative paths.

Story

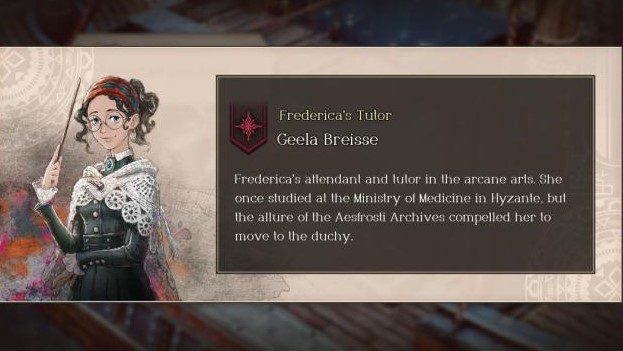

The story of Triangle Strategy is told from the perspective of Serenoa Wolffort, a young noble heir in the Kingdom of Glenbrook, and primarily centers around three key protagonists: Benedict Pascal, war veteran and advisor to the Wolffort family, Frederica Aesfrost, princess of the Grand Duchy of Aesfrost, and Roland Glenbrook, second son of the kingdom’s royal family. The story starts off three decades after a major conflict between the nations of Norzelia, Glenbrook, Aesfrost, and the Holy State of Hyzante, with only an uneasy truce holding things together. The three powers are in the process of consummating a new age of peace, with our heroes being drawn into these tense politics through the arranged betrothal of Serenoa to Frederica. The story has a fairly slow opening as it introduces you to all of its major players, but it’s not too long before events hit their crescendo and all of the different factions and characters collide in a grand tale full of twists and turns. Mainly by the choices you as the player make throughout the story.

Yes, Triangle Strategy’s most notable feature is its multiple choice approach to storytelling. While the story only splits off into truly different endings in the later chapters in the game and earlier choices return back to a central narrative, these choices keep the player engaged quite well and it is really fun to see how events play out according to your decisions. It may be surprising to hear it was fine that choices didn’t change most of the story despite being a “choices matter” game, but this is because these choices feed back into a fascinating alignment system called Convictions. Serenoa’s worldview is passively governed by three convictions: Morality, Liberty and Utility, and the decisions aligned with each one are hidden to the player except for during major decisions, where they are associated with the colors green, red, and yellow respectively. These decisions are handled via democratic votes which you can manipulate by persuading your trusted advisors, however even the best arguments fall on deaf ears if Serenoa’s convictions are at odds with that decision. Effectively speaking this means that the real story being told up until the final vote is about the kind of person the protagonist is, and the outcome of the final decision is directly tied to who Serenoa becomes overtime. Observant readers may have also noticed that the number of convictions and supporting protagonists are equal, and indeed the marketing for the game created the impression that Roland, Frederica, and Benedict were to be paragons of a given conviction. In a happy twist though, applying this mindset only works up to a certain point, and ultimately trying to read the characters as mere symbols breaks down entirely. This allows these protagonists to stand as genuine ‘people’ like the other characters in the story, and I appreciated that level of nuance.

With all of that said however, there is one major issue with this setup, and that is that the final decision’s various paths seem to have been written as options for the player to pick from before they were proposals by the characters in the story. This is an issue, because while two of the supporting protagonists fit their respective routes just fine, the third is ultimately forced to make extremely strange logical capitulations in order to make their route an option. Even if one were to make the decisions earlier in the game that overall would best inform the conclusions this character comes to, it still would not excuse the fact that out of the main cast this character is one of the few with direct, firsthand witness to the utterly horrifying tradeoff this route entails, and flies in the face of the character’s clearly defined self-sacrificing nature. It’s all just a really unfortunate situation, and a glaring weak spot in the character arc of what is otherwise one of the game’s most compelling and complex protagonists, sacrificed in the name of player choice.

While on the topic of endings, I wanted to briefly mention that this game has a secret ending which can be unlocked by making specific choices throughout the game, and basically amounts to getting the happy ending as opposed to the bittersweetness of the game’s main endings. Both the specificity of the options required to reach this ending and the mechanics of the battles featured in it make it clear that it’s meant to be reached during New Game+ mode and not on a first run. While I haven’t seen this route for myself and am totally oblivious to its actual quality, I nevertheless feel that its very existence is a detriment, as it basically implies that all the engaging character building you’d been doing with Serenoa was secondary to the story actually trying to be told. I have seen “golden endings” used to further the themes of video game stories in powerful ways, but in a game about challenging your convictions and striving not to regret your path (as flawed as a message like this can be) it just doesn’t sound right. Maybe this wouldn’t be such a problem if I hadn’t played Fire Emblem: Three Houses and found it to be the golden standard of how to use a lack of a fully happy ending to make all of its narrative routes feel more poignant (even despite the uneven quality of its routes), but alas, I am a simple biased human and cannot deny these feelings.

One last major comment I would like to make on the story regards the Morality conviction. I’m sure many readers became hesitant hearing morality ascribed to one of the game’s three main alignments, because as I stated in my Path of Champions analysis article, selecting an option because a game tells you it is the virtuous one can sometimes lead to a faulty picture of right and wrong if the developers hold faulty views themselves. To this end I decided to play the game selecting only Morality decisions at the story branches, with the one branch that was purely Freedom vs. Utility being decided by my best understanding of Catholic principles, in order to judge whether this is the case. Thankfully, I am pleased to report that taking the Morality options whenever possible involves taking actions that faithful Catholics can reasonably endorse. There can be arguments made for the alternative options at these decisions which are almost beautiful in their subtlety, and sometimes the justifications of certain options being the Morality ones require nuances of their own, but on the whole they tend to represent virtues such as filial piety, preserving the sanctity of life, and upholding the duties of one’s station. The Morality ending itself is a difficult decision to make, with tragic consequences for Norzelia you will be well aware of when you make it, but I ultimately commend the writers for correctly identifying it as the most righteous path of the three normal endings.

So to summarize, the story of Triangle Strategy has some issues in its execution, especially in putting player choice before tight writing at times, but on the whole its highly unique narrative structure and surprisingly engrossing script make for a tale well worth telling. I doubt we’ll see a game handle its story in quite the same way for a long time yet, but hopefully when it does happen it will learn from both the triumphs and stumbles of this title and give us something really special. Whew, that was a lot to cover for the game’s story huh? Well as we move into the gameplay section, know that the game operates on the same logic too. One of Triangle Strategy’s most divisive elements is its gameplay-to-cutscene ratio, as many others have pointed out you can potentially do nothing but soak in the game’s story for over an hour at a time, especially if you choose to watch all of the optional cutscenes (which I recommend as they give helpful context). As you might have guessed this isn’t really an issue for me, but if you dislike story-heavy games… I’m surprised you even made it this far into this article!

Gameplay

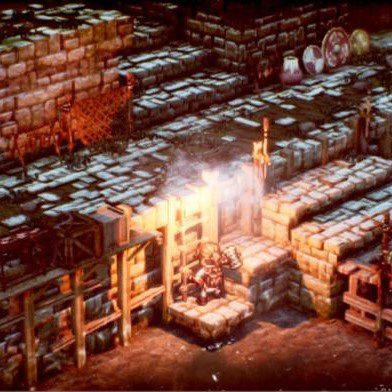

The core gameplay of Triangle Strategy on the surface is pretty standard fare for the genre. Your units and the enemies on a grid-based map, where you take turns moving about the environment to use abilities, deal damage to overcome your foe, and survive while doing it. The maps themselves are mostly differentiated from similar titles I’ve played through its elevation system, where different tiles on the grid are physically above or below others, and this has a major effect on the way the game is played. Attacks from higher ground typically deal more damage and have their effective range extended, so gaining a foothold on cliffsides and sniper perches can be decisive in your success. The game’s maps can also feature gimmicks like fortifications to break through, or secret traps to activate, so the variety from level to level is pretty fun and challenging. Most of the levels simply involve routing all enemy forces, which is understandable since the few maps that are cleared by defeating the boss or escaping at a certain exit are prone to cheesy strategies, but a little more variety in this regard would have been welcome. Positioning is naturally pretty important too, as striking enemies from behind deals free critical damage and attacking a foe with an ally on the other side allows them to deal a follow up strike, but these mechanics are all at the disposal of both player and opponent so learning how to leverage these advantages while minimizing risk of falling prey to them yourself is an engaging facet of the learning curve.

What really sets the combat apart is the army of up to thirty different heroes you can bring to battle. Some are recruited through the story, others by raising the various Convictions to certain thresholds, but all are completely unique in their mechanics, playstyle, and personalities. From a simple swordsman dishing out consistent damage, to mages with varying kinds of elemental spells, to an apothecary who turns those healing items you never use into an impressive source of sustained healing, there’s no end to the variety of roles your characters play. Even those characters whose abilities seem weak at first simply require you to experiment and find out just how good they can be. You might think the artificer Jens looks pathetic with one of his selling points being the ability to build ladders of all things, but if you give him a chance you’ll quickly realize how utterly ridiculous it can be to bypass the restrictions of the map design or a character’s low jump stat and reposition your team in such a way that snowballs into a clean victory. This is all smartly managed by a Technique Point meter which allows you to play with each character’s abilities without allowing you to spam the best stuff endlessly, though there are strategies available to bypass even those limits. The balance of the characters certainly isn’t perfect, bowmen in particular allowed me to clear maps I didn’t deserve to win on multiple occasions, but it’s hard to be mad when every character is useful as long as you’re willing to discover the synergies that make it happen.

One final point of discussion about the combat design is the game’s leveling system. The extent to which the game is more strategy or RPG focused is a very big point of contention for critics of the genre, and in Triangle Strategy’s case it winds up being a bit of a mixed bag. On one hand, clever use of the mechanics presented to you will allow you to triumph over most of the battles without really having to grind out levels. On the other hand though, reaching the recommended level for each chapter, while not totally trivializing the strategic aspect, is very helpful for turning a losing fight into a manageable one. To say that this game even has a ‘grind’ though can be a little misleading, as it uses a rubber band Exp system where characters gain more experience from taking actions in combat based on the levels of their foes. Overpowered characters seem to eventually stop leveling altogether, while underpowered characters can potentially gain a level every turn. My recommendation is to treat every optional skirmish in the Encampment as a mandatory fight to keep the game at a nice strategic equilibrium, however there’s certainly nothing stopping you from rushing into the next chapter, metaphorically throwing yourself onto the enemies’ pikes to get fat stacks of Exp, then retrying the level to play for keeps (Exp is retained on loses and retreats).

The Encampment serves as a semi-diegetic party customization area where you can buy items, upgrade your characters’ equipment, and generally outfit them for battle. All of it is fairly intuitive and unobtrusive; probably one of the more relaxing implementations of numbers management I’ve seen in an RPG. Of particular note is the Kudos Shop, which sells everything from class promotion items, to extra lore entries for the game’s War Chronicle menu, to powerful boosts you can use in battles to give yourself an extra edge called Quietuses. This shop deals in special currency obtained primarily for performing actions in combat such as performing follow up attacks and hitting several enemies at once. I personally always like systems that encourage skillful play, but at least Kudos are afforded relatively generously so that less skilled players aren’t totally left in the dust.

Last in terms of gameplay, there are the exploration sections of the game where the player traverses one of the game’s maps and talks to various characters to collect items, strengthen Convictions, collect information, and pet cats. One would think these would be fairly comfortably skipped over considering the usually lacking dialogue of townspeople in RPGs, but in truth the information you can collect may or may not be the key to making persuasion at the voting sections go your way. As such the game cleverly found a way to get me to pick these sections clean without actually forcing me to, and in that respect I am compelled to applaud them for it. Others might find this frustrating for sure, but on the whole I think a game encouraging the player to engage with its systems is part of its job, and it’s certainly better that these town sections feel worth your time then not.

Presentation

The graphics of Triangle Strategy follow in the footsteps of Square Enix’s other throwback role-playing game Octopath Traveler, featuring an eclectic mix of pixel sprite characters, low fidelity three-dimensional environments, and modern lighting and visual effects which culminate in an distinctive artstyle dubbed “HD-2D”. This style definitely has the mark of an acquired taste and won’t be to everyone’s liking, but personally I loved the art direction in Octopath Traveler and this title pretty much brings back everything good about it. While the more freeform camera present in Triangle Strategy does cause the game to lose some of its predecessor’s forced-perspective magic (and to some degree can be a little disorienting) the art team has done a good job compensating for this change, with the cinematic camera work and visual effects of late-game special attacks being a major highlight. I could watch Frederica cast Sunfall for days.

The music in the game is also one of the best soundtracks I’ve heard in a while. While the track selection might be a little limited given the game’s run time, it’s impossible to not get swept away in the soaring orchestrals that accompany every step of Serenoa’s journey. You would think that the vocal arrangement of the game’s main theme, Song of Triangle Strategy, could never possibly be good when these japanese vocalists open the main chorus by literally singing “Triangle Strategy” then moving into their mother tongue, and indeed it would be so easy to tease the song for it. But the piece is so resolute in its delivery, and travels through such a symphony of different emotions and musical ideas, that by the time the song is rushing towards its finale you can’t help wondering why you thought the chorus was so funny in the first place. Definitely a soundtrack worthy of Square Enix’s legacy.

Wisdom and Conclusion

As for what we can take from Triangle Strategy as Catholics, it’s difficult to identify a central moral which will apply to every playthrough since there are technically over 2000 possible orders of events that could unfold depending on the player’s choices. Additionally, the idea of striving not to regret one’s path is a decent idea, but the questionable morality of certain choices in the game makes this message a little misguided in execution. After all, feeling regret for a path of sin can be the seed of a person’s salvation. Perhaps what could be best taken from this game as a whole is in the subtext of the way the votes work in this game. As I’ve stated earlier, the person Serenoa becomes is altered by the character he, and by extension you, expresses in words and deeds, and this in turn affects the difficulty of swaying his allies towards a given decision in the votes. While there is definitely an artificial fantasy to the system, as it’s perfectly reasonable to believe that one could have a character of a certain stripe yet truly convince others to do something out of the ordinary for themselves for a variety of reasons, I think it is a sobering reminder of how important it is to live by the morals we wish to see upheld.

Someone hostile to the idea that there is a correct way to live one’s life, a way such as by following the Word of Jesus Christ, might claim that so long as their actions harm no one, people should just be free to live out whatever ideals they see fit. But people live as a community, and the ideals of one person can have a profound effect on those communities. If we falter in the righteousness of faith and lead others by poor example into sin, then if the day comes where we wish to walk back towards the light, we might have to walk that path alone while the others rest content in the sinful example we’ve hypothetically provided. One needs only to look to our brothers and sisters who have been led astray by heretical catechesis, and the subboness some hold to it, for proof of this. For Serenoa Wolffort it could be the desire to help a person in need thwarted by his own pragmatic method of leadership in the past, for us it could be failing to help those closest to us overcome a vice which we ourselves previously downplayed. Regardless the message is clear: hold fast to the virtues you want to see passed from your own example to others because they are watching and being shaped by you, especially the young (Saint Dominic Savio, ora pro nobis).

In conclusion, Triangle Strategy is a fascinating and nuanced tactical experience with fun and innovative mechanics, and a narrative structure wholly unlike anything else. It may have made a few poor decisions which hold it back from achieving everything it set out to accomplish, but the truly great elements present make the story of the land of Norzelia well worth seeing through, multiple times even! The star of strategy role-playing games may still be rising, but once it reaches its zenith I hope a little bit of House Wolffort shines through it. Look past the endlessly mocked name, because Triangle Strategy has got it where it counts.

Scoring: 95%

Gameplay: 5/5

Art and Graphics: 5/5

Music: 5/5

Story: 4/5

Replayability: 5/5

Morality/Parental Warnings

Bear in mind that due to the immensely divergent nature of the game’s content, I was unable to see everything that happens in the game. While I am confident this section reflects the overall breadth of moral and parental concerns, there is potentially other content you may take issue with that I simply haven’t seen.

Triangle Strategy is a game whose narrative is centered primarily around the intrigue and warfare waged over the fate of the continent of Norzelia. As such the game’s combat features its characters fighting with swords, spears, and other such armaments. Characters sometimes die and bleed out over their final resting place during cutscenes, but the rest of the time defeated characters just dissipate in a shroud of light. Some characters use magic as their form of combat, but it’s mostly just the ability to blast around lightning bolts or mend wounds and not anything that resembles real magic. The most extreme the game gets in this regard is just that one of the playable characters is a shamaness. The antagonists of the game are not above committing various war crimes to achieve their ends. The morality of the protagonists is affected directly by the player, but they can on occasion choose to take morally repugnant actions, including lying, complying with criminal acts, harming innocents for your own ends, ect. One character makes an off-hand comment which alludes to moral relativism. While the number of characters wearing sexualized outfits is delightfully low, and those who do wear them have their effect dampened by the pixel artwork, the character artwork will flesh out the details pretty explicitly, such as with the dancer Milo. Milo herself speaks largely in innuendo. There is at least one scene wherein it is implied sexual activity is taking place, but it is out of frame and passes quickly to other matters. Foul language is not uncommon during dialogue. The game features an oppressed race called the Roselle who are treated pretty brutally, and certain player choices allow the player to perpetuate it.

The game also features a highly villainous fantasy religion, the Holy State of Hyzante, which places it in the long line of Japanese role-playing games with the trope my brother and I so elegantly refer to as, “church bad.” I always find this worth mentioning, if for no other reason than to save you the trouble if negative depictions of theism are draining to you. That being said, the fantasy religion in question actually gets most of its aesthetic inspirations from Islam rather than the usual convention of using Catholicism as the base, so on the whole it is at least easier to engage with the narratives surrounding Hyzante without being hit with constant subliminal messaging.